The latest crisis in Iraq has yet again exposed India's vulnerability in hydrocarbon supplies. Yet neither the citizens nor the government of India seem to realise just how precarious their position is.

India's luck in overseas energy investments has been quite poor, largely because it has put most of its eggs in a highly volatile Middle Eastern basket.

The civil war in Syria has washed away India's investments in the country as the terrorist group Jabhat al-Nusra has captured the Dayr al-Zawr, al-Sham, and Block XXIV oilfields. The conflict in Sudan similarly sent ONGC Videsh scrambling out of the country in 2012 and South Sudan at the end of 2013.

In Iraq, ONGC Videsh's holdings in Block VIII are now under threat as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) are swinging south after capturing Mosul, Tikrit, and Baiji.

Iraq has been offering India three oil blocks -- Kifil, West Kifil and Merjan -- in the Middle Furat region since 2000, and Reliance Industries has been eyeing the Nasiriya Integrated Project but all those will now be on hold until ISIS is repelled. However, the oil infrastructure at the southern port of Basra has not been affected though there is talk of evacuating personnel if the Islamist rebels are not turned back.

Reliance sold its Rovi and Sarta blocks in Kurdistan to Chevron in 2012 under threat of blacklisting from the Iraqi government. Unfortunately, Delhi did not step in to ensure that an Indian corporation received fair treatment and the country is paying a price for this short-sightedness. Due to intense pressure from the United States, India also shifted some of its oil purchases from Iran to Iraq, the latter replacing the former as India's second largest supplier last year. The developments this year have proven that shift as unwise.

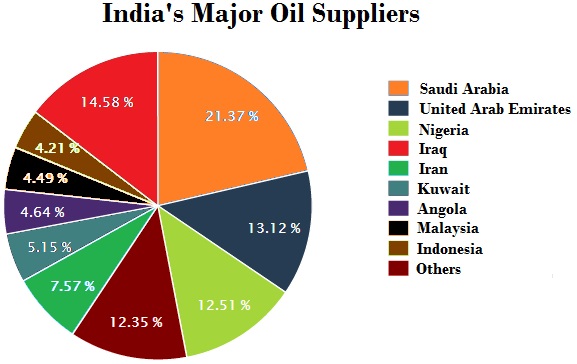

India's oil suppliers

India is the fourth largest consumer of oil and also the fourth largest importer. Approximately 80% of India's oil --190 million tonnes -- is imported and the annual expenditure in 2011-2012 was approximately Rs7,26,386 crores.

With so many sources of oil going offline, oil prices are expected to spike up to $130 in the near term. This will not only affect India's total import bill but will make the state's vast subsidies -- Rs1 lakh crores on kerosene, petrol, and diesel and Rs68,000 crores on fertilisers -- even more unbearable. On the whole, the Middle East represents over 66% of India's energy imports -- more if the entire Arab World were considered -- and the chaos in the region bodes ill for India's energy security.

India's energy policy has many weaknesses, not the least of which is a failure to augment the Indian Strategic Petroleum Reserves (ISPR) and plan for a post-oil future via nuclear and solar energy to power electric vehicles.

However, its more immediate blind spot is the lack of strong diplomatic support to its economic forays and its failure to diversify into more stable markets.

Until recently, its timidity could be chalked up to its anaemic economic footprint. However, with increasing economic might and more global interests must come commensurate military power and diplomatic acumen. Be it Matthew Perry, Robert Clive, or the Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, this has been the behaviour of Great Powers. While the face of this economic superiority may have mellowed somewhat over the years, the trade and diplomacy of Great Powers go hand in hand to this day.

To be fair, India's foray into unstable markets was not out of ignorance. Investing in undesirable countries meant little competition from the more established Western multi-national corporations like Shell, BP, and Exxon. Due to either sanctions, unacceptably high risk, or being barred, Western MNCs could not access many of the markets Indian and Chinese oil giants could.

Delhi has pursued this strategy since the mid-1990s and it has paid of handsomely until now. ONGC Videsh went from an insignificant public sector unit on the verge of being dissolved to becoming a player of some consequence in the international oil market with 33 projects in 16 countries. The investments in Sudan, for example, increased the company's profits six-fold from 2003 to 2010.

The price of these advantages has been made apparent in the past two years. With its assets languishing in the Sudans, India has been trying to diversify its oil portfolio. India has interests in Azerbaijan and Burma as well as Russia's Sakhalin islands. Unfortunately for energy-hungry India, only some projects are moving ahead while others have been derailed or put on the back burner for now. An oil pipeline from Russia to India through China's Xinjiang province has been under discussion since 2005, but this could be risky given India's fractious relations with its northeastern neighbour.

Another project that has been tangled on the drawing board is a deepwater pipeline for gas from Qatar, Oman, and Iran to India. When first envisaged in the mid-1990s, such a pipeline would have strained existing technology but new advancements have made construction of a such a project possible now within three years.

It might be worth considering expanding this project to include crude oil. Linked to the region is the prospect of the International North-South Trade Corridor (INSTC) which could give Central Asian oil & gas resources another way to international markets via Afghanistan and Iran's Chabahar port. This project has also been in the doldrums due to sanctions on Iran and pressure on India from the United States not to take the venture forward.

India has also diversified its search for hydrocarbons to Canada and it is already Nigeria's largest oil export partner. However, diversification alone will not solve India's problems. Nigeria is yet another troubled state on the fringes of Islamist violence that has spread across northern Africa, and transportation costs from Canada or the United States may prove dear.

However if India chooses to diversify its hydrocarbon portfolio and overall national energy mix, it must learn to ensure the sustainability of its overseas investments in the face of local political crises.

India needs to participate, when needed, in regional structures that promote stability and the rule of law via economic incentives, diplomatic pressure, and the threat of force. Otherwise, India will find itself becoming an expert in hightailing it out of countries.

India's allergy to developing regional political networks that could insure against calamity has left it the perpetual outsider in international fora. On Sudan, Syria, and Iran, Delhi has taken a most vacuous and unhelpful position over the past four years and has paid the price for it. China, the referent nation for Indians, has, on the other hand, been active in discussions on Africa as well as the Middle East.

Many unstable markets India wishes to expand in, such as Burma, Central Asia, or Russia, do not see eye-to-eye with the United States and/or the European Union. Delhi must be prepared to face pressure from the West to protect its interests in these states purely out of a sense of realpolitik as the West would do (Pakistan, anyone?) were the situation reversed. Delhi has paid the price for its hesitation to engage with Iran, for example, as it may have done even otherwise. With engagement, however, at least India gets the hydrocarbons.

India's continued reliance on international infrastructure has also hurt its quest for energy. While the United States put strong pressure on India not to invest in Syria or purchase hydrocarbons from Iran, similar pressure on its East Asian allies was not apparent. European refusal to insure oil carriers did not hurt Iran's other major customers -- China, Japan, and South Korea -- nearly as much as it did India. Delhi cannot develop its options in lag as it fumbles from one crisis to another. The rational course would be to anticipate such crises -- there have been plenty before -- and be prepared for them.

Delhi's diplomatic inadequacy is a burden to its economic interests. The upheaval in the Middle East has dramatically reduced India's oil production and sent it frantically looking for other suppliers. If India intends to continue trading with weak and/or authoritarian states, the almighty rupee must be accompanied by honeyed diplomacy and a mighty stick as well.