In villages across Maharashtra, Dalit burial grounds are being usurped by upper castes; families trying to access them face brutal reprisals.

If pain had a face, it could be Narayan Sonawane’s. The 45-year-old Dalit farmer keeps scratching a shaving wound on his face till it bleeds, and makes him flinch. The pain, perhaps, momentarily takes his mind off the gruesome reality outside his hut — a seven acre plot that used to be a Dalit cremation ground until a year ago.

In June 2010, it was usurped by upper caste Maratha farmer Mahadeo Khandu. And on this day, as Sonawane stands watching mutely, Khandu supervises the tilling of the land. The land where the bodies of Sonawane’s parents were laid to rest.

“I buried my father here two years ago. And my mother a year before that with my own hands,” says Sonawane, fighting back tears. “Would upper castes let this happen to their own dead?”

As a crowd gathers around, a nonplussed Khandu shouts, “Don’t listen to him, he’s lying.” But he quickly changes tack. “Come now... We are all from the same village. Why take such petty differences to the media?” Seeing that his words have had no effect, he adds, “I’ll build a shed for you to cremate your dead. I don’t even want money for building it.”

We soon discover the reason for Khandu’s generosity: the appropriated land is worth Rs30 lakh at market rates, while the steel shed with asbestos sheet roofs will cost a mere Rs30,000!

Khandu and Sonawane belong to Mhalsapur-Zavla village in Beed district, which falls in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. Such casual take-over of Dalit lands by upper castes is fairly common, not just in this district, but all over Maharashtra. According to figures compiled by the Maharashtra ministry for social justice, Dalit burial grounds have been usurped by upper castes in with 72.13% of the state’s 43,722 villages.

About 150 km from Mhalsapur-Zavla, in Parbhani district’s Devalgaon village, the tension is palpable. It has been less than a week since violence erupted over a Dalit’s attempt to bury a deceased family member in the demarcated cremation ground. Upper caste men stopped the funeral procession, brutally attacked the pall-bearers, and flung the body of 39-year-old Shevanta Pawar to the ground. The pall-bearers, including Pawar’s husband, Mahesh Pawar, 42, barely escaped with their lives.

Recalls a bitter Mahesh, “Upper caste men attacked us and threw my wife’s body into the bushes nearby. After we lodged a complaint with the tehsildar, the police arrived, and only then could we recover the body from the bushes and do the last rites.”

Despite the violence, and the tension in the village on account of it, the upper castes are unrepentant. “This is our way of life. Those who don’t like it here are free to leave,” says Dhanajirao Kale, an obviously well-to-do upper caste farmer. Kale even has a word of advice for us, “It is better that you city folks stick to what you know and understand.”

Adding insult to injury

Nearly 60 km away, the Dalits of Malegaon still can’t forget November 22, 2008. On that fateful day, upper caste men led by priests of the local Khandoba temple, Sanjay and Ganptrao Naik, attacked a funeral procession with sticks and swords because they were taking a dead body to the designated crematorium. “They beat up everyone and forced them to flee with my father’s body, which then lay in our house for two days,” remembers Urmila Waghmare, daughter of the deceased, Ramchandra Waghmare. “When the body began to decompose and smell, we had to cremate it on the roadside,” she adds, tears welling up in her eyes.

When Dalit rights organisations like Samajik Nyay Andolan forced a reluctant police to lodge an FIR, reprisal from the upper castes was swift —the Waghmares’ home was burnt down. Urmila’s distraught mother Mandubai suffered severe burn injuries but survived. While the culprits, thanks to their political patrons, move around freely, Urmila and her mother live without a roof over their heads. Promises from the then collector, Radheshyam Mopalwar, that they will get a house under Indira Awaas Yojana have remained promises. “Every time I go to the social welfare officer, he asks me to come later,” says Urmila.

There are, of course, instances where official apathy has reduced even death to a farce. Like in Madalmoi village of Georai tehsil in Beed, where the 0.275 acre crematorium (Survey No 357) was first given to the Dalits by the Nizam in 1354. It was encroached upon by a wealthy Maratha, Sonaji Bhopale, in 1965, and subsequently sold to a local money lender, Sitaram Govind Harkut.

Complaints from the Dalits led to a law suit, which is still pending in court. So after every death, the Dalits take the dead body and lay it in the middle of the busy highway for a rasta roko. “Once we create a traffic jam, the cops and the tehsildar scurry to the spot, and only then are we allowed to perform the last rites on the allocated land,” says Sarjerao Shinde, a resident of the village.

The Marathas are calling it blackmail. “Why can’t they wait for the case to be decided by the court if they know they are right?” asks an angry Harkut.

‘Marathwada is worst’

These are by no means isolated incidents. In fact, since there have been several such incidents in the constituency of BJP general secretary and deputy opposition leader in the Lok Sabha, Gopinath Munde, and in Dehu village in NCP chief Sharad Pawar’s constituency.

When contacted by DNA, Munde admitted that the problem existed in his constituency, but was quick to add that it was prevalent across the state.

“I have myself raised this issue several times, first in the state assembly and then in the Parliament, but the government is not serious about addressing this long-standing issue,” he said. When asked why the NDA government did nothing about the issue during the Sena-BJP reign in the state, he said, “Undoing what the Congress had allowed to fester for 45 years is not an easy task,” adding, “If the Dalits unite, mobilise and take to the streets on this issue, I will gladly join them gladly in their fight.”

Article 17 of the Constitution abolishes all forms of untouchability. But the reality is otherwise even when it comes to burying/cremating the dead. In hundreds of villages and hamlets across Mahahrashtra, Dalits are not only denied access to the common burial/cremation ground but prevented from using even the burial grounds specifically demarcated for them.

“The level of friction over the issue is the highest in Marathwada, where over one-fifth of the population is Dalit,” explains Eknath Avhad of the Manavi Hakk Abhiyan, which has been fighting for Dalit rights in the region.

“Dalit youth of today do not want to wait endlessly for justice to prevail. Their increasing aggression is seen by upper castes as a challenge to their social and economic status.”

Will justice ever be done?

Dalits have traditionally had separate tracts of land to dispose of their dead as a part of the caste system. “In Maharashtra, these are on the eastern side of the village, so that the whole village is not ‘polluted’ by the winds blowing from the direction of the Dalit cremation ground,” points out Ganpat Bhise of the Samajik Nyay Andolan, a Parbhani-based organisation fighting for the restoration of these cremation tracts to Dalits.

“The upper castes want to usurp Dalit cremation grounds, and they also do not want us to cremate our dead anywhere else. Where do they want us to take our dead and go?” asks Bhise. “Why then don’t they allow us to use the same crematoria that they do?”

He says claims of progress on integration and mainstreaming of Dalits ring hollow on the ground, and remembers how the then Nanded collector had mocked him during a protest against the Malegaon incident, asking, “Do you expect the Collector to go to every Dalit’s house and help him fight for justice?”

Access to cremation/burial grounds has become an increasingly sensitive issue over the last decade as population has grown. Land, always a contentious resource, is more so in this arid belt, which has the lowest per capita income in the state. “It is ironic that in the birthplace of BR Ambedkar, Dalits continue to be denied dignity even in death,” observes Eknath Avhad. “The government’s inability to resolve this issue even six decades after Independence has only created another reason to keep the caste cauldron on the boil.”

Same story across the country

Punjab: A paradox of Sikhism

Though Dalits form 30% of Punjab’s population, and though Sikhism frowns on discrimination in the name of caste or creed, untouchability against the Mazhbis and Ramdasias, the two Dalit castes among Sikhs, is well established. They have been forced to live in separate settlements, contemptuously called thhattis or chamarhlees, and forced to reside on the western side, away from the main area of the villages, so that the winds blowing over them don’t pollute the upper castes. All the Sikh organisations, from Sikh temples to the political parties, are under the control of the Jat Sikhs, who refuse to consider Dalit Sikhs equals even after death. The former disallow cremation of the latter’s dead in the main cremation grounds. Over the years, such harsh discrimination has forced Dalits to establish separate gurdwaras, marriage places and cremation grounds. This, in many ways, is the biggest paradox of Sikhism, which is often characterised as ‘emancipatory’ and ‘revolutionary’.

Tamil Nadu: Evidence of atrocity

A study by the Tamil Nadu Untouchability Eradication Front (TNUEF) shows problems relating to burial and burning grounds in over 75% of the state’s 30,000-odd villages. The NGO Evidence found that Dalits had faced atrocities over burial/cremation in 208 of the 213 villages covered by their survey. In 153 villages, Dalits were not allowed to carry their dead through areas where the dominant castes lived. In 132 villages, Dalit graveyards do not have water, power or a cremation shed.

Gujarat: it’s ‘wasteland’

According to the Ahmedabad-based Behavioural Science Centre (BSC), of the 18,100 villages in the state, 5,000 have no legal burial grounds for Dalits. Though the Dalit custom of burying the dead is an age-old one, the government doesn’t recognise it. As a result, the unregulated lands are classified as wasteland. Despite the fact that the Revenue Department had passed a GR in September 1989 to consider 1972 as the year for earmarking land for burial, nothing has been done so far.

![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results

Vellore Lok Sabha constituency: Check polling date, candidates list, past election results![submenu-img]() Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...

Meet NEET-UG topper who didn't take admission in AIIMS Delhi despite scoring AIR 1 due to...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now

Remember Tanvi Hegde? Son Pari's Fruity who has worked with Shahid Kapoor, here's how gorgeous she looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now

Remember Kinshuk Vaidya? Shaka Laka Boom Boom star, who worked with Ajay Devgn; here’s how dashing he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

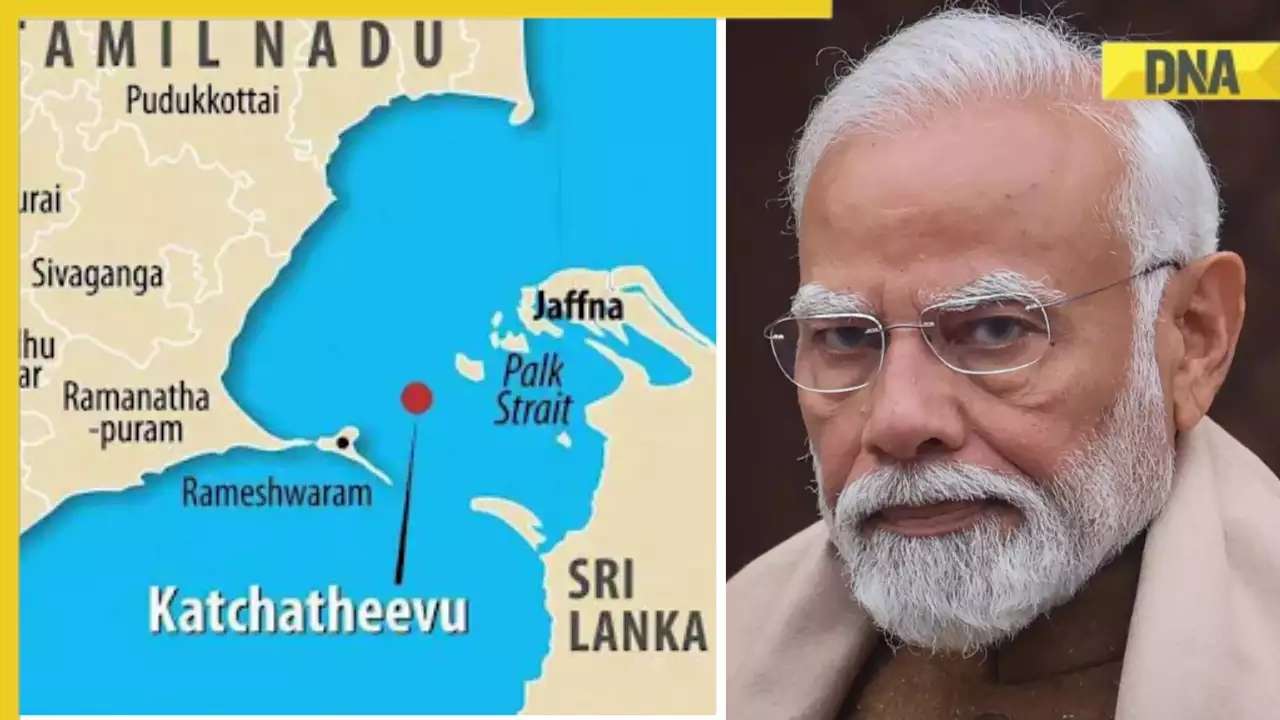

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur

DNA Explainer: Reason behind caused sudden storm in West Bengal, Assam, Manipur![submenu-img]() Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins

Firing at Salman Khan's house: Shooter identified as Gurugram criminal 'involved in multiple killings', probe begins![submenu-img]() Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'

Salim Khan breaks silence after firing outside Salman Khan's Mumbai house: 'They want...'![submenu-img]() India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat

India's first TV serial had 5 crore viewers; higher TRP than Naagin, Bigg Boss combined; it's not Ramayan, Mahabharat![submenu-img]() This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3

This film has earned Rs 1000 crore before release, beaten Animal, Pathaan, Gadar 2 already; not Kalki 2898 AD, Singham 3![submenu-img]() This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit

This Bollywood star was intimated by co-stars, abused by director, worked as AC mechanic, later gave Rs 2000-crore hit![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

RCB vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Royal Challengers Bengaluru vs Sunrisers Hyderabad ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants

IPL 2024: Phil Salt, Mitchell Starc power Kolkata Knight Riders to 8-wicket win over Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?

IPL 2024: Why are Lucknow Super Giants wearing green and maroon jersey against Kolkata Knight Riders at Eden Gardens?![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS

IPL 2024: Shimron Hetmyer, Yashasvi Jaiswal power RR to 3 wicket win over PBKS![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)