Encephalitis has claimed thousands of lives in Gorakhpur over the years. DNA digs deeper to find out what has made this Eastern UP district a burial ground for children, and what needs to be done to control future outbreaks

Monsoon clouds bring hope and cheer in India. In Gorakhpur, they signal disaster. The otherwise crisp, earthy scent that fills the air when rain falls on parched fields coincides with an air of despair in this Uttar Pradesh (UP) town lying just south of the India-Nepal border. Encephalitis patients, mostly children and infants, are rushed to the Baba Raghav Das (BRD) Medical College. The hulking, sprawling network of buildings begins its annual descent into chaos. It's time for Gorakhpur to count and mourn its dead.

The first deaths in the latest cycle were reported on August 7, but outrage started mounting only four days later when children and infants began slipping away, one by one, as oxygen supply was cut by a private firm over pending bills. There have been 105 deaths since August 10. Many were sick with encephalitis and other tropical diseases.

Thirty one deaths took place on August 10 and August 11 alone. Helpless parents cried and screamed. Some had babies dying in their arms. Relatives tried to support hospital staff using manual breathing bags. Children spit blood as tender lungs collapsed one by one. All this sparked a firestorm of public criticism and a political slugfest. The tragedy prompted Prime Minister Narendra Modi to issue a call for the country to stand shoulder to shoulder with people of the border town.

Shooting in the dark

Acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) is most often caused by contaminated food or water, besides mosquito bites. It mainly affects malnourished children, causes brain inflammation and can result in headaches, seizures, fever and even brain damage, or coma.

Patients often require assistance to breathe. Doctors at the hospital say they have been treating patients for symptoms.

"AES can be caused by any of the several viruses, bacteria and fungi. The term AES was never meant to be a diagnosis. It's a convenient label for symptoms, a surveillance tool for a host of illnesses such as scrub typhus, dengue, Japanese encephalitis (JE), pneumonia, mumps and measles. For 50 per cent of patients, there is no real diagnosis," says a senior doctor at the hospital.

She says all these illnesses require different approaches. "For example, JE is caused by a virus found in pigs, water birds and livestock. It is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. Scrub typhus is caused by a bacterium transmitted by a microscopic mite found in scrub vegetation, common in Gorakhpur. There is no one illness called encephalitis."

The Centre has been focussing on scrub typhus since 2014. "Our studies show scrub typhus cannot cause encephalitis outbreaks. Plus, intravenous azithromycin, pushed by the Centre, does not work here," she says, while admitting that expert opinions at Central government institutions differ. "Now that the High Court has stepped in, we hope serious studies will be undertaken."

What ails Gorakhpur

Founded in 1969, the 900-bed hospital caters to a population of over five crore from 15 districts of Eastern UP, 10 districts of Bihar and bordering Nepal. The hospital has a 100-bed Special Encephalitis Ward, a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, an Intensive Care Unit and an Isolation Ward to treat infants suffering from encephalitis. The hospital is equipped with all modern medical facilities, with piped oxygen supply, to save children from the killer disease.

But the disease has claimed some 10,000 lives at the hospital since 1978. It became a national crisis only in 2005 when more than 1,000 children died. A total of 567 children died in August 2014. And as many as 668 and 587 in August 2015 and 2016, respectively. Figures show 18-19 deaths of children, on an average, occur every August.

Much of the problem lies outside the 147-acre campus. The district has a 37 per cent shortage of health sub-centres. Only 45 per cent of villages have access to a sub-centre within five kilometres. It's often too late when patients reach the hospital. Other issues include contaminated water, malnourishment and extremely poor sanitation. Stagnant water covers the roads and garbage is dumped almost everywhere. UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has acknowledged Gorakhpur's poor hygiene, triggering a cleanliness campaign in the town and elsewhere in the state that ranks among the bottom three big states in India on health infrastructure.

"But the situation at the hospital is much better now. Not too long ago, there were no catheters. We manually carted oxygen cylinders. We knew that half the kids who came to us would not survive. We wanted to save as many as possible. If no child died during a particular doctor's shift, it was a trophy moment," says another doctor at the hospital that has now become a symbol of India's swamped, mismanaged and corrupt public healthcare system.

Government figures tell us why. The previous Akhilesh Yadav government had in its last budget (2016-17) allocated Rs 15.9 crore. But the Yogi Adityanath government slashed it to Rs 7.8 crore for 2017-18.

Not only this, the present government also cut funds to the hospital for purchase of equipment from Rs 3 crore to a paltry Rs 75 lakh for the current fiscal year.

Families want answers

Scenes at the hospital will haunt families forever. "They were gasping for breath when the oxygen supply was cut after 7.30 pm on August 10. We were given Ambu bags to pump in life into our own children if we wanted to save them from death. I pumped in desperately to save my six-day-old baby, my only daughter. Her body was turning blue. Life was leaving her slowly and painfully. Finally, she took a long deep breath and she was still," recalls Sunita Rajbhar, whose husband Manager Rajbhar had paid Rs 400 to a ward boy for the admission of their child.

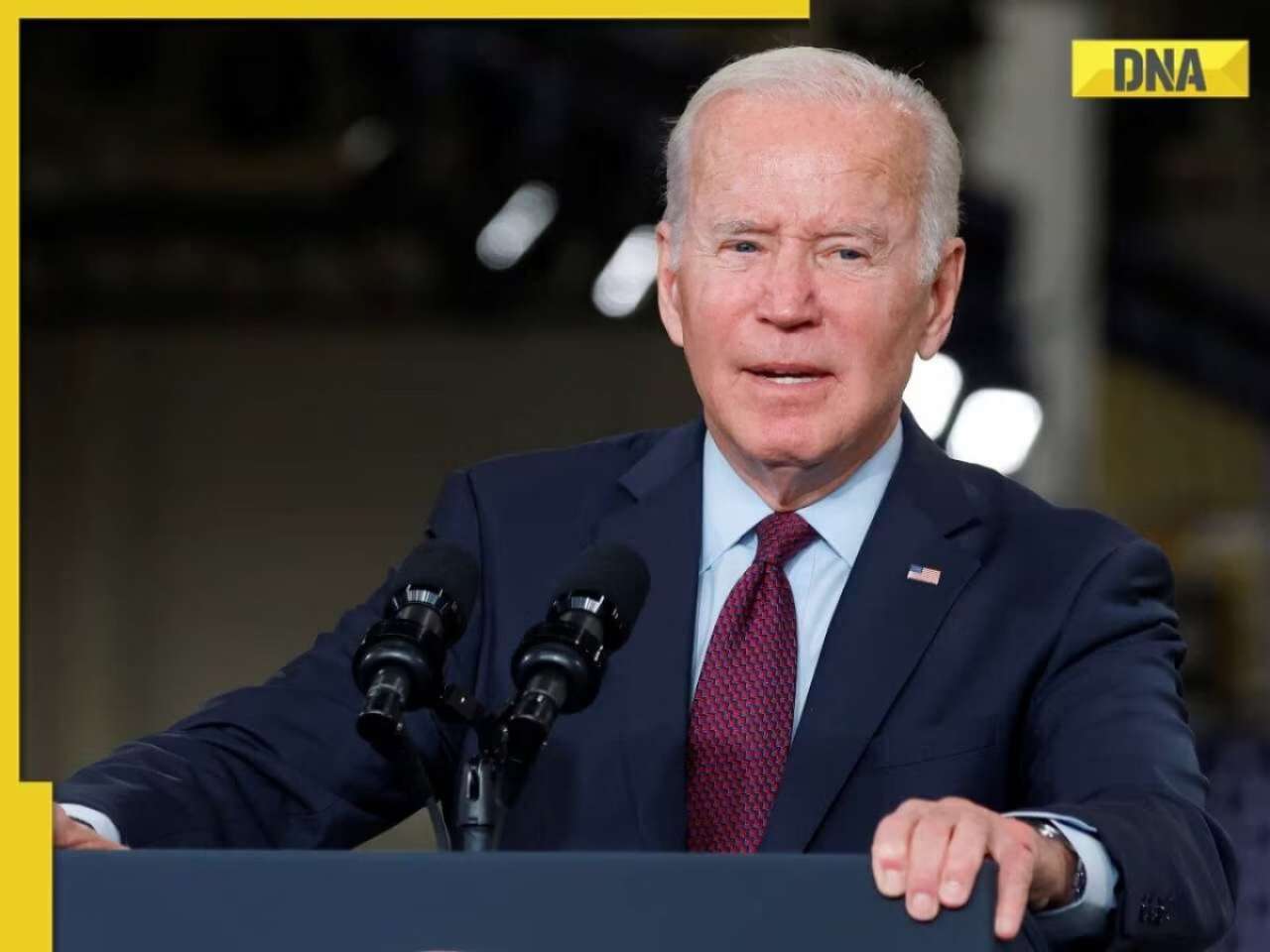

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)