Lines are drawn between women’s and men’s rights activists over Indian Penal Code’s Section 498A, a legislation heavily tilted in favour of women

Software engineer Raghav Iyer is startled every time the phone rings. His septuagenarian father Balasubramanian and 65-year-old wheelchair-bound mother Meenakshi, weep as he recounts the nightmare his life’s been reduced to since the last two years.

“Ever since my 28th birthday, my parents were after me to marry. I gave in a year later when mom bought up her poor health and dad’s rising age.”

Accordingly, word was passed around in the community to find a girl for Raghav and a civil engineer-turned-interior designer from Hyderabad was found. “We had a long meeting with my in-laws and Ratna. We even went out for movies and dinner dates several times. She was friendly with my parents. I saw that as a great sign since we were going to live together.”

They married after a courtship of about three months. “We travelled through the US on our month-long honeymoon where we visited my sister in San Antonio for a day in December 2013. She seemed to enjoy this trip and enthusiastically posted photos on Facebook.”

First signs of trouble began after they returned to their home in Mumbai. “She felt we should live separately. I pointed out that my parents were old but she insisted. By Mumbai standards, 1,500sq feet is huge. My parents are often in a self-contained bedroom with their own TV. When they found out about this, my mother got an induction hob in the room so that she won’t have to go to the kitchen. But even that wasn’t good enough.” After creating a scene, Ratna left for Hyderabad with her clothes and jewellery. “I bought her flight ticket and called her parents to receive her. I told them what had happened. They said they’ll make her understand.”

Even though she had cleaned out the cupboard, Raghav didn’t think much of it. A call from Ratna’s brother a week later set off the alarm bells. “He threatened to file a case against me for beating her up,” Raghav remembers being stunned. “In fact, she’d broken the drawing room TV and clawed me when restrained.”

Soon after, a case was filed in Hyderabad alleging torture and harrassment under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), Section 498A and Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (DV) against Raghav, his parents and even his San Antonio-based sister Malavika, who, it was alleged, had “tortured Ratna on the phone.”

Police then came to Mumbai to arrest Raghav and his aged parents. They were taken to Hyderabad where they spent a fortnight in the lock-up. “If it weren’t for my father, who collapsed while in detention, we would’ve never gotten bail. My mother’s spirit was broken after this and she is wheel-chair bound. In the building, all that everyone knows us for is the arrest. My parents have even stopped going to the temple.”

After calls from his in-laws, his firm threw him out. He has managed to find work again but the court cases in Hyderabad keep him shuttling back and forth. “All my earnings are spent in legal fees and in my parents’ medical treatment.” He says he has contemplated suicide. “The thought of what it’ll do to my parents prevents me.”

Is the line between fighting for women’s rights and brazen misandry blurring? Because Raghav’s case isn’t an isolated one. Latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) statistics show every nine minutes a married man commits suicide in India. That means a whopping 64,000 suicides by men every year, twice that of women. “Unlike in case of women where the NCRB classifies deaths as dowry or marital violence related, here it is left in the realm of the unsaid. This invisiblises the sheer number of men forced to take their own lives in face of cruelty from their wives,” points out men’s rights activist Amit Deshpande of Vaastav Foundation, a men’s rights group working in the area of advocacy for gender-equal laws.

He should know what he is talking about having experienced being trapped in a bad marriage and having fought off false 498A and DV cases. “I realise how alone a man must feel with laws stacked against him and society judging him based on a woman’s false accusations,” he adds.

According to Bangalore-based marital counsellor Sudha Rao, instances of husband harassment and abuse have reached “epidemic” proportions. “This is further fuelled by avarice of lawyers who incite women into taking recourse to these laws by promising to get them more money and property, a percentage of which eventually goes into the lawyer’s pocket as fees,” she says. “Driven by this greed, sensitivity, empathy, justice and equality are given the short shrift. The damage we have done to society will only emerge in another decade or two. By then, the toll of this injustice will be too huge.”

Noble intent gone wrong

Commonly known as the anti-dowry law in India, Section 498A of the IPC was first introduced in 1983, after national outrage over unprecedented and widespread dowry-related harassment and killing.

It was felt that such a law will empower women by making offences under it non-bailable (only courts are empowered to grant the accused bail). It also made it mandatory for police to arrest the husband (and often his family) forthwith, merely based on a woman’s complaint.

Over the years, Section 498A has become a potent tool to subjugate and oppress husbands.

“The sheer damage wreaked by the misuse of 498A has far outdone any benefits it may have brought to Indian women,” says Rao, adding, “Even the Supreme Court has asked the legislature to re-look the law.”

Kids caught in between

Stock broker Aritra Mukherjee points out how even children are not spared by raging women, out to bring a man to his knees. “My wife has filed six cases of domestic violence in her hometown Baroda and in her maternal uncles’s hometown Indore. She contends that I accosted her and beat her up in public. I have not seen my son and daughter since two years. Though the family court has given me visiting rights, she has continuously called me to various places and stood me up.” He breaks down remembering his son’s ninth birthday. “I’d taken a cake and a gift and waited there for five hours but she never showed up like she had agreed to in court.”

Ask why he hasn’t complained to the court, and he laughs: “Are you serious? Do you know the speed at which our courts work? It will take months for a hearing to happen, and my precious time with my children will be gone.”

View on women’s rights

Advocate Flavia Agnes, who runs the women’s rights advocacy organisation Majlis, says she is aware of the growing clamour from men to make women friendly laws more gender neutral. “However, given the disproportionately larger number of women who suffer abuse and harassment compared to men, I am not in favour of making these laws gender neutral. It’ll open doors to cross complaints, further frustrating women’s fight for justice.” She went on to ask how many women from marginalised classes actually find anyone willing to take down a complaint. “There is a reason the unheard woman has been given an upper hand in the laws. Any effort to change that will take the whole campaign against domestic violence for which many gave given their blood and toil back be several decades.”

(Some names have been changed on request)

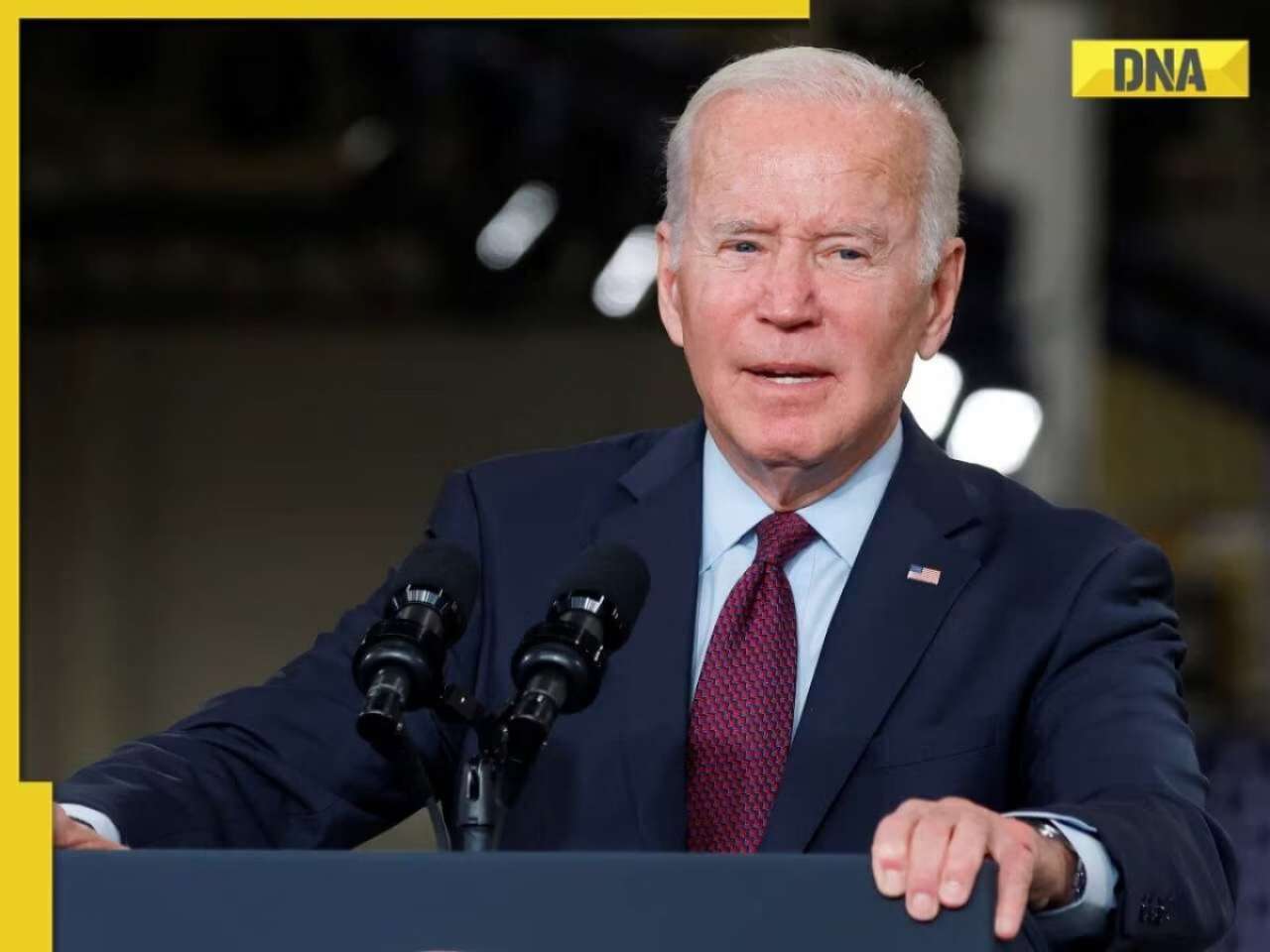

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)