The court observed that the issue of right to privacy goes to the very heart of liberty and freedom which have huge repercussions for the democratic republic called 'Bharat'

Three judges of the Supreme Court in separate judgements today said the issue of right to privacy goes to the very heart of liberty and freedom which have huge repercussions for the democratic republic called 'Bharat' whose constitutional culture is based on protection of human rights.

While Justice R F Nariman said the importance of this matter is such that whichever way it is decided, it will have huge repercussions for the democratic republic that we call 'Bharat', Justice S A Bobde said this reference has been made to them to answer questions that would go to the very heart of the liberty and freedom protected by the Constitution.

Justice D Y Chandrachud said the issue reaches out to the foundation of a constitutional culture based on protection of human rights and enables the Supreme Court to revisit the basic principles on which the Constitution has been founded and their consequences for a way of life it seeks to protect.

Justice Nariman, in his separate verdict, said, "Our judgments expressly recognize that the Constitution governs the lives of 125 crore citizens of this country and must be interpreted to respond to the changing needs of society at different points in time."

Justice Bobde also said the issue has arisen in the context of a constitutional challenge to the Aadhaar project, which aims to build a database of personal identity and biometric information covering every Indian that is the world's largest endeavour of its kind.

Justice Nariman held it was clear that the right to privacy is an inalienable human right which inheres in every person by virtue of the fact that he or she is a human being.

"This reference is answered by stating that the inalienable fundamental right to privacy resides in Article 21 and other fundamental freedoms contained in Part III of the Constitution," he said.

The judge, however, said right to privacy is not an absolute right and is subject to reasonable regulations made by the state to protect legitimate state or public interest.

He said when it comes to restrictions on this right, the drill of various articles to which the right relates must be scrupulously followed.

"In the ultimate analysis, the balancing act that is to be carried out between individual, societal and State interests must be left to the training and expertise of the judicial mind," he said.

The judge rejected the arguments of the Centre and Maharashtra government that the right to privacy is so vague and amorphous a concept that it cannot be held to be a fundamental right.

He said that mere absence of a definition which would encompass the many contours of the right to privacy need not deter the court from recognizing privacy interests when it sees them.

The judge said the concept has travelled far from mere right to be let alone to recognition of a large number of privacy interests.

He said it now extended to protecting an individual's interests in making vital personal choices such as the right to abort a foetus, rights of same sex couples- including the right to marry, rights as to procreation, contraception, general family relationships, child rearing, education, data protection, etc.

The court said it is too late now to assume that a fundamental right must be traceable to express language in Part III of the Constitution.

Describing right to privacy as a fundamental right in Indian context, the judge said it would cover at least three aspects including "privacy that involves the person when there is some invasion by the State of a person's rights relatable to his physical body, such as the right to move freely."

The other two aspects are, "Informational privacy which does not deal with a person's body but deals with a person's mind, and therefore recognises that an individual may have control over the dissemination of material that is personal to him. Unauthorised use of such information may, therefore lead to infringement of this right.

"The privacy of choice, which protects an individual's autonomy over fundamental personal choices," he said.

Justice Nariman rejected the Centre's argument that in a developing country where millions of people are denied the basic necessities of life and do not even have shelter, food, clothing or jobs, no claim to a right to privacy as a fundamental right could be made.

"A large number of poor people that Attorney General K K Venugopal talks about are persons who in today's completely different and changed world have cell phones, and would come forward to press the fundamental right of privacy, both against the government and private individuals.

"We see no antipathy whatsoever between the rich and the poor in this context," he said.

The judge further said it seems that this argument was made through the prism of the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016, by which the Aadhaar card is the means to see that various beneficial schemes of the government filter down to persons for whom such schemes are intended.

"This 9-judge bench has not been constituted to look into the constitutional validity of the Aadhaar Act, but it has been constituted to consider a much larger question, namely, that the right of privacy would be found, inter alia, in article 21 in both 'life' and 'personal liberty' by rich and poor alike primarily against state action. This argument again does not impress us and is rejected," he said.

![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…

Apple iPhone camera module may now be assembled in India, plans to cut…![submenu-img]() HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating

HOYA Vision Care launches new hi-vision Meiryo coating![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

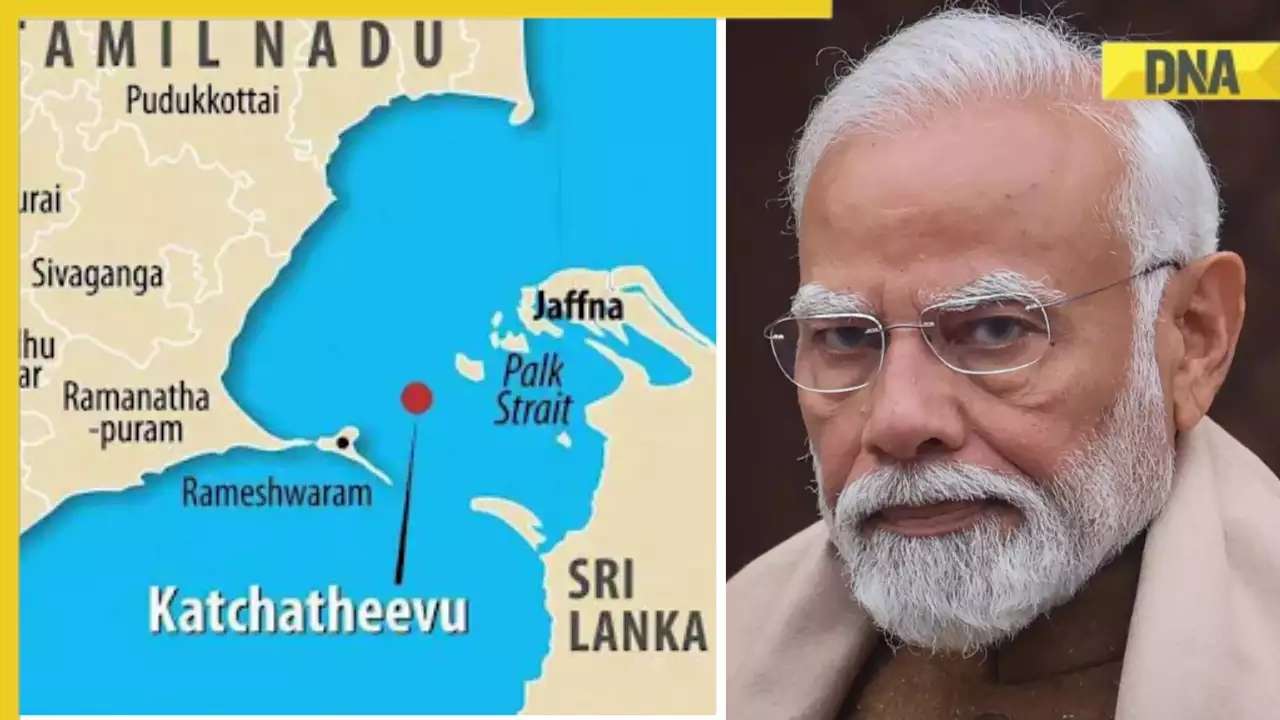

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..

First Bollywood star to wear bikini was called greatest actress ever, later isolated herself, died alone, her body was..![submenu-img]() This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...

This film had no superstars, got slow start at box office, was made with budget of only Rs 60 lakh, earned Rs...![submenu-img]() Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans

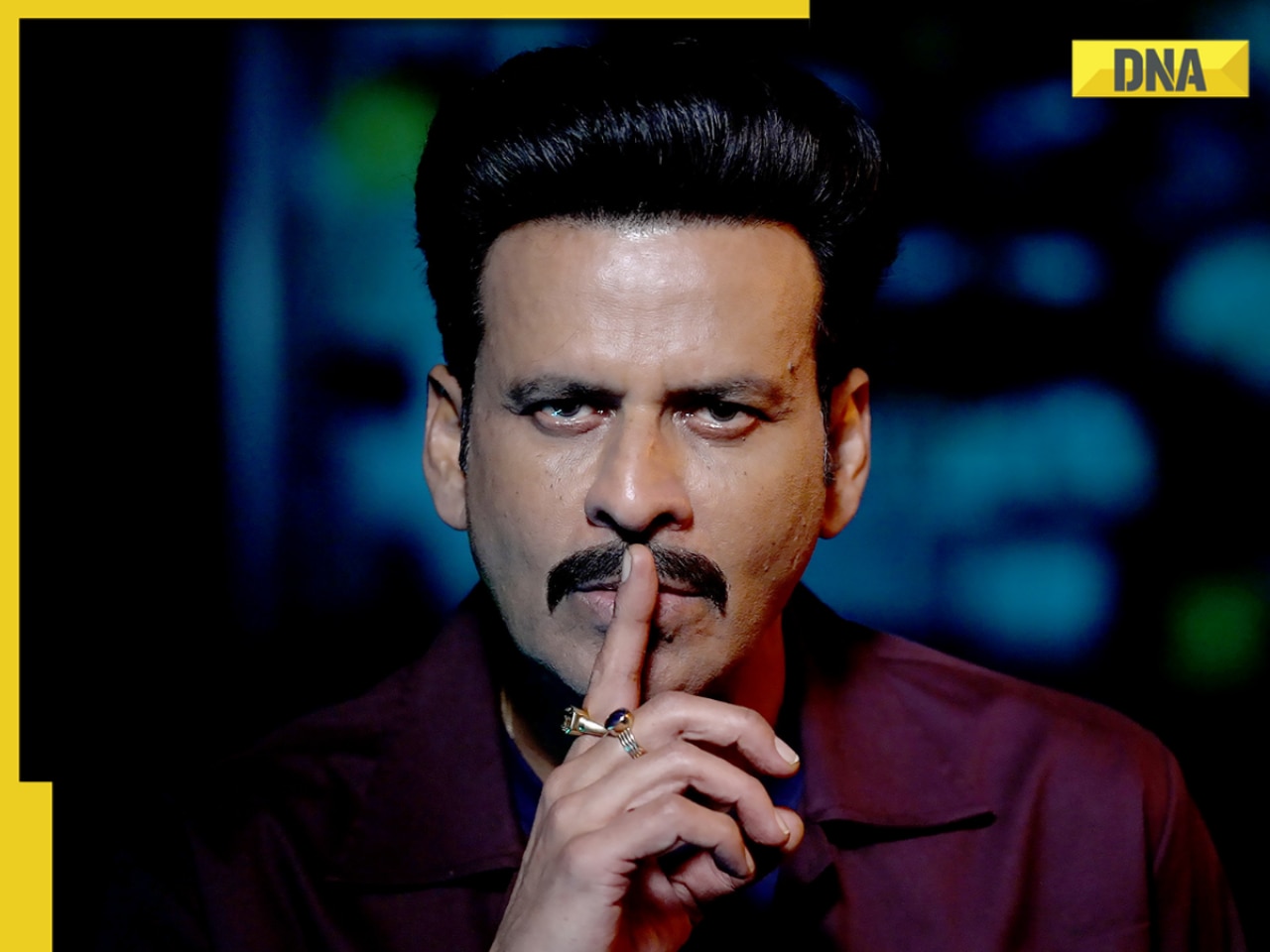

Salman Khan to return as host of Bigg Boss OTT 3? Deleted post from production house confuses fans![submenu-img]() Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive

Manoj Bajpayee talks Silence 2, decodes what makes a character iconic: 'It should be something that...' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now...

Meet star, once TV's highest-paid actress, who debuted with Aishwarya Rai, fought depression after flops; is now... ![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR

IPL 2024: Jos Buttler's century power RR to 2-wicket win over KKR![submenu-img]() GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

GT vs DC, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals

GT vs DC IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Gujarat Titans vs Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash

'I went to...': Glenn Maxwell reveals why he was left out of RCB vs SRH clash![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places

Shocking details about 'Death Valley', one of the world's hottest places![submenu-img]() Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here

Aditya Srivastava's first reaction after UPSC CSE 2023 result goes viral, watch video here![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)

)