Well water is pumped into a large overhead tank, which is connected to small plastic tanks on platforms installed in two locations across the state highway (connecting Latur and Osmanabad), which runs through Dastapur.

Dusty Dastapur has been on a three-day wait. “We were told we will have water on Saturday, eight days after the last tanker filled the local well,” rues Ambabai Nijalingappa.

Well water is pumped into a large overhead tank, which is connected to small plastic tanks on platforms installed in two locations across the state highway (connecting Latur and Osmanabad), which runs through Dastapur.

The branches of a young neem tree offer little respite from the 42 degrees Celsius heat, and the octogenarian's cataract eyes water. “If I sat at the doors of the Pandharpur shrine as long, God would call me to heaven.”

Of the more than 800 homes in the village, almost all have only elderly and children. “There is no work, water or food. Most adults work in places like Pune and Aurangabad,” says Shevantabai Dakne, 60, herself a domestic help with a doctor's family in Latur city.

“Both my sons and daughters-in-law run a food cart in Viman Nagar, Pune. I came back because my mother-in-law's sick and there's no one to care for my grandson,” she sighs and adds, “Only if we had water, all our problems would be over.”

The village is in the same tehsil of Loharia as the 91 MCM Lower Terna dam at Makni village in Osmanabad district.

The water body, constructed in 1970, was supposed to address the kind of drinking water needs like Dastapur's. Though, at dead storage, it has 5 MCM (million cubic metres) of water, all canals leading out of the dam are bone-dry, just like two jack-wells meant to provide water to Nilanga and Osmanabad towns.

But there is one that continues to suck up the receding waters from the reservoir for the Lokmangal sugar factory owned by BJP MLA Subhash Deshmukh.

When dna visited the site on Monday afternoon, workers were using an earth mover to deepen a trench so that more water could flow into the jack-well.

Questions like who granted permission to this sugar mill or why or how did a dam's waters become a private resource elicit only silence from Osmanabad collector Prashant Narnaware.

He denied any political pressure, and said: “Cutting off water for sugar factories during the crushing season can create law-and-order problems.” He goes silent again when asked if the neighbouring collectorate of Solapur can do it, why can't Osmanabad.

Deshmukh was evasive, but his son Rohan, a director on the factory board admitted to both – the factory and the jack-well. “We only lifted water during crushing season. Now we don't need water, so we aren't,” he told dna. “We only do this to help poor sugar cane farmers.”

Just below the dam, the shop which sell provisions in Makni village, is shut. “I am tired of waiting for customers. People don't have money and no one comes to buy even a matchbox. How will they? Repeated crop failures due to drought has left them with no money,” explains owner Arvind Patil who wants sell his entire inventory to another shopkeeper.

“Everyone says no or quotes such a low price that I decline. They say they're also facing the same problem. With every passing day, I'm worried. Instead of giving it to the rich, why can't they release the dead stock of water to the thirsty poor? It'll provide drinking water to over 2 lakh people for six months.”

Barely two hours away, in Latur tehsil's Pakhar Sangvi village, people form a long line with pots and buckets before a tap, which brings water directly from the Dhanegaon dam, built to supply water to Latur. Their wait is in vain.

So, where is the water? Mallikarjun Patil, a local, points to the imposingly grand White Field, a residence being readied for local legislator Amit Deshmukh, son of late Vilasrao Deshmukh, twice Maharashtra CM. Well-watered, the gardens inside look lush green.

“Even if we beg and plead for a pitcher to drink when they're watering plants, they don't give us,” complains Shashikant Ghodke, a second-year college student.

“Not everyone can afford the Rs 150-200 private vendors ask for 10 litres. How can they have water to splurge on a garden and get to pick up water from the Manjara barrage for his sugar factory, when we are thirsty?”

dna called Deshmukh for a reaction. “These are baseless lies spread by political opponents,” he said, insisting the water connection at White Field was legal but unable to explain why villagers weren't getting water.

He denied lifting of water for the crushing season by his sugar factory from Manjara barrage. “We use water from sugar cane itself. And whatever minimal water we've lifted is in accordance with the permissions given when the factories started.”

Water rights experts like Vjay Diwan, who think otherwise, point out how the Dhanegaon dam, which has a live storage capacity of 174 TMC live water, has been hit by the 30-50% deficit in the Manjara river volume over the last five years.

“Obviously, people expect that resources, at least when depleting dangerously, will be equitably distributed. When there was water, sugar factories and plantations were drawing as much as 1,300 MLD while not giving Latur city even 50 MLD per day!”

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

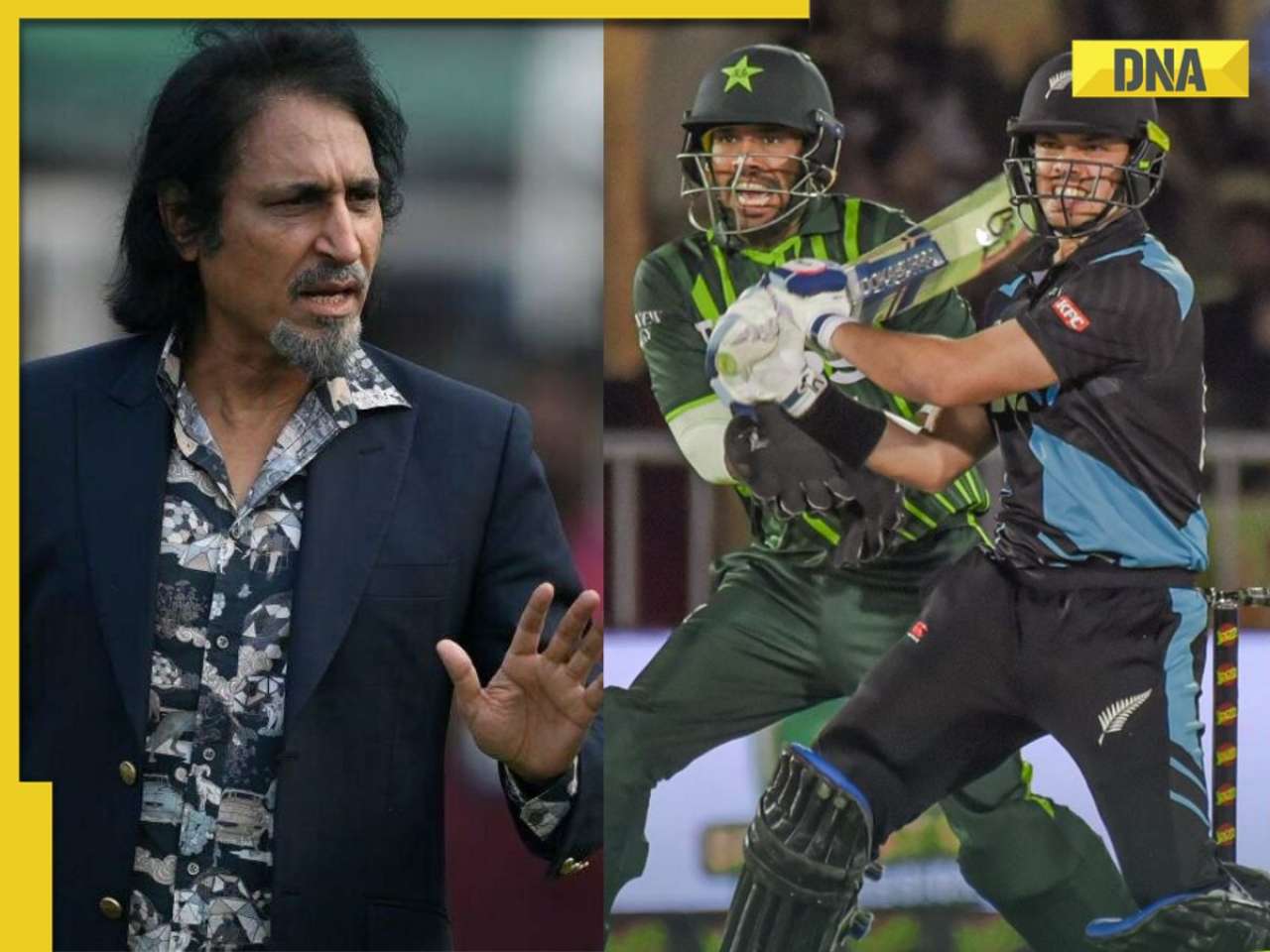

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

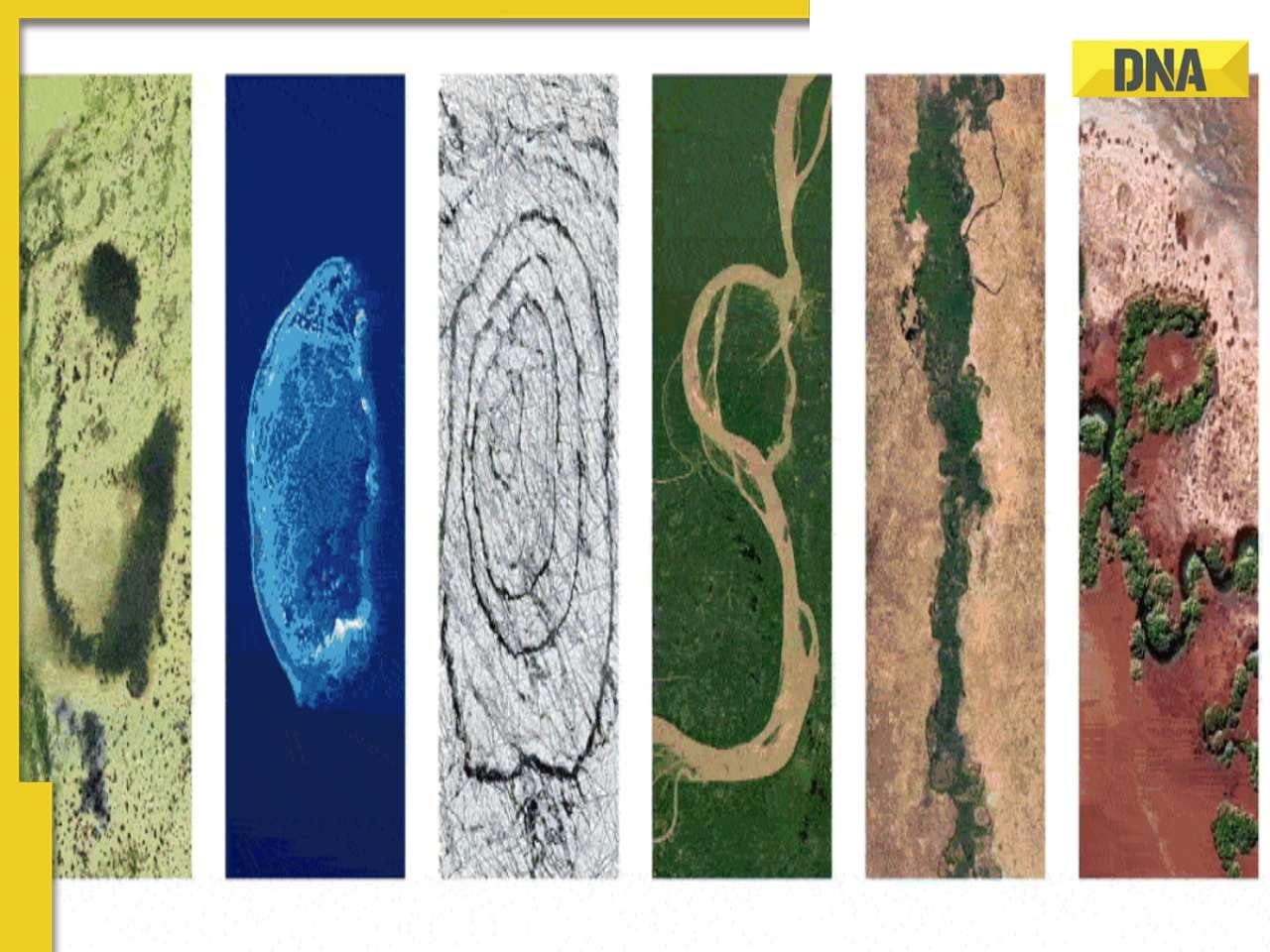

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)