On the hazy morning of March 18, 15-year-old Sheetal Davatpure was nervous. Her SSC board exams had started and she was gearing up for a paper. Four of them still remained before she could breathe a sigh of relief. Little did she know that on returning home that evening, all tension about board exams would suddenly seem trivial. After wishing her luck and reminding her to take her hall ticket, her father Gurunath Davatpure, 38, headed for his farm only to end his life.

Two weeks previously, incessant rains and hailstorms in several parts of Marathwada destroyed miles of crops and swamped the farmlands of thousands of farmers, including Gurunath's.

"All hope gone. Nothing left," Gurunath had said after realising that the labour he put in all season on his 6.5 acre farmland in Khandapur was devoured by the calamity. The disaster crushed his hopes of repaying a Rs 1.75 lakh loan he had taken, the burden soon becoming unbearable.

Before leaving the house for the last time, Gurunath ate food made by his wife Sushma, then spent an hour in a nearby temple before proceeding to the farm, where he hanged himself from a tree. A lawyer who owns the neighbouring land found Gurunath and broke the news.

"Though the situation was gloomy after the hailstorm, we didn't notice any change in his behaviour that indicated such a drastic step," Sushma said. "He was always subdued".

In Marathwada, the seeds of most debts are sown in marriages. Living in a feudal society, a wedding means the bride's family has to provide a handsome dowry, along with household items like a TV, fridge, and utensils among others to satisfy the groom's family.

However, Gurunath stood out.

He borrowed every penny with only one aspiration: educating his children. 17 years ago, Gurunath made the decision to shift 10 kilometres from Khandapur to Latur, where there are good schools. He went back and forth to his farmland in Khandapur on his bicycle every day. With Sushma contributing to the family income by sewing, the family was just about managing until disaster struck.

"Farming has now becoming akin to gambling," said Atul Deulgaonkar, a noted author who has written extensively about farmer suicides. "Even if the rains are good, the crop is excellent, and everything goes smoothly, farmers still do not get the profit they deserve. Agents decide rates and make profits at the cost of farmers. Farmers end up just about managing and have nothing to fall back on in case of calamity or irregular rainfall."

Since 1995, more than three lakh farmers have taken their lives in India. According to the 2011 census, the suicide rate for farmers was 47% higher than the national average. 33,752 have occurred in Maharashtra alone from 2003 to 2012, at an annual average of 3,750.

The government has failed to address this system where agents milk farmers and, according to local activists, efforts regarding compensation have not been satisfactory. Sushma said the family did not even get the Rs 1 lakh declared by the government for the family of a farmer who commits suicide. Sitting in her rented two-room-house in Latur, a regretful smile on her face, Sushma said the inspectors who visited Gurunath's farm to assess the damage thought a generous amount of Rs 6,000 was appropriate compensation.

"Apart from the compensation, it is also important to provide them psychological support to let them know someone is looking after them," said Madhav Bawge, chief secretary of Andhashradha Nirmulan Samiti. "Many families were spared the trauma of suicides after we travelled with psychiatrists through the hailstorm affected areas. But an NGO cannot reach every nook and corner. The government has the arsenal to do that, but it has not been done."

However, despite getting the cold shoulder from the authorities, Sheetal's resolve was unbroken. She went ahead with the remaining exams and passed with 59% marks. "It was tough," she said. She plans to go to college and aspires to be a lawyer. Why? "Nobody is worried about the problems of the poor. While travelling with my parents, I have seen the disparity. I want to fight for their problems by becoming a lawyer", she said.

The situation at the Davatpure household, though, is still grim, with over half the loan remaining to be paid. The family pays Rs 2,000 per month as rent, spends Rs 2,500 on ration and Rs 6,000 as the bank instalment.

But Sushma is not worried about that. "I have savings over the last 17 years, so I can manage my house." Her biggest concern is education. The eldest son, 17-year-old Suraj studies science in Class 12 and his fees are Rs 40,000 per year. School fees for the youngest, 14-year-old Sagar, are Rs 25,000 per year. Courtesy government provisions in educating the girl child, Sheetal's education is fortunately not financially heavy.

In order to meet these expectations, Sushma has increased her sewing work. A shelf right next to the entrance, filled with colourful clothes, made this quite apparent. Next to it is a photograph of Gurunath mounted on the wall.

Sushma now carries the burden of a debt, but she is determined to fight on. "My husband wanted our children to study," she said. "I will make sure they do."

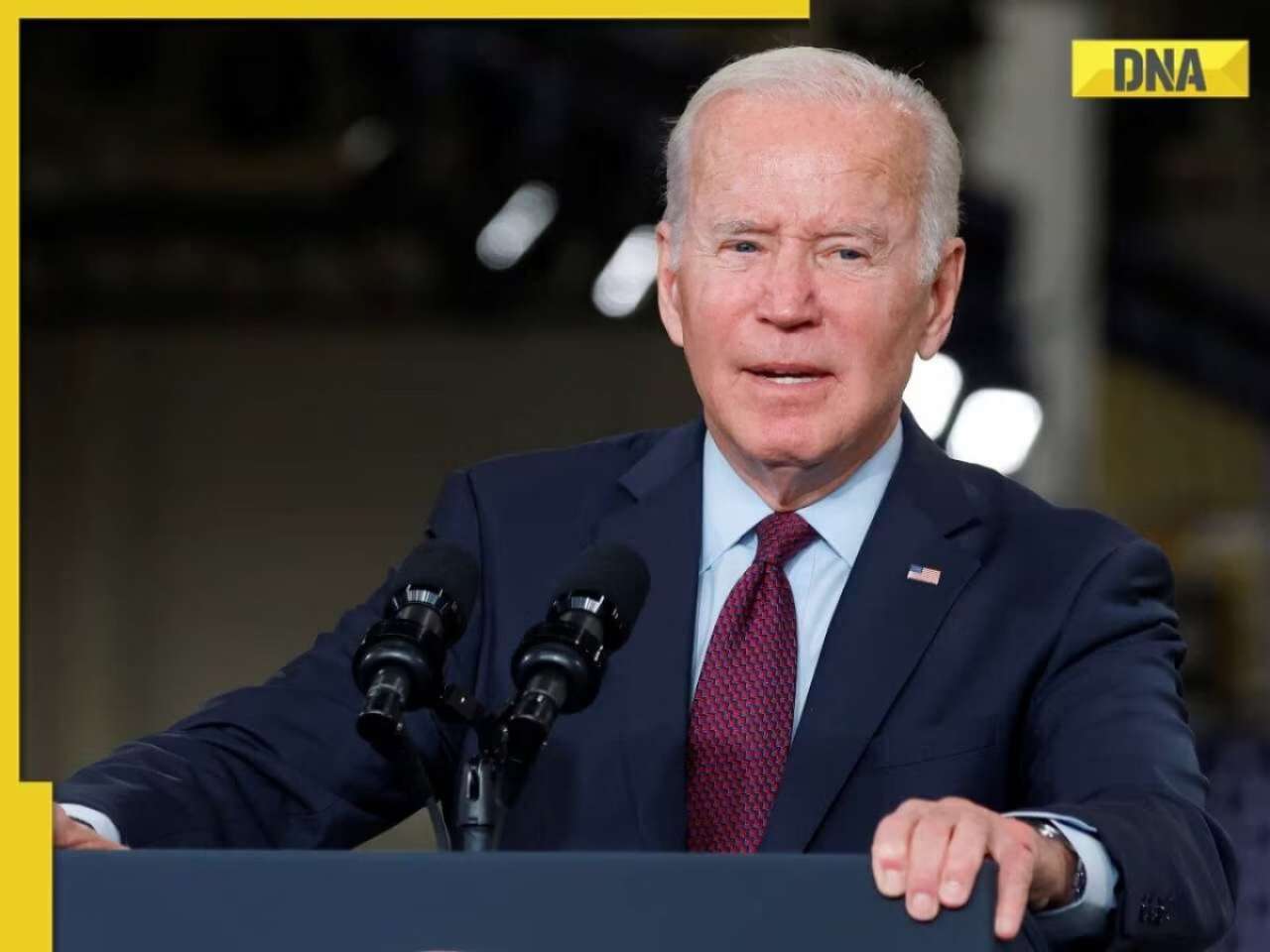

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)