Health care takes a hit as doctors scramble to private institutions for fat salaries and safer work environment. DNA finds out that a flawed recruitment policy means there are not enough replacements

Ravi Prakash, a resident of Uttar Pradesh’s Bareilly, stands in a winding queue at Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital every day. His wife, Smita, has been diagnosed with a neurological disorder, and is being treated there. “She has to undergo a surgery. We’ve been waiting here for more than three months now. There are only two doctors in the department, busy looking after those who came before us. Her condition is deteriorating. I can just hope something is done before it’s too late,” says the worried husband.

Thousands of people are suffering similar trauma every day as premier government hospitals in Delhi face an acute shortage of doctors. Most exits have been triggered by fat salaries and better work environment offered by the private sector. In some cases, frequent violence in government hospitals by angry relatives of patients has also been a reason. A flawed recruitment policy has worsened the situation.

The All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) is short of 863 doctors, including 241 faculty members, 458 senior resident and 164 junior resident doctors. Across the street, Safdarjung Hospital has a shortage of 423 doctors. The number for Ram Manohar Lohia (RML) Hospital and Lady Hardinge Medical College (LHMC) is 157 and 152, respectively.

While many of these state-run institutions are losing experts to private ones, they are also struggling to fill vacancies, with “unattractive” salaries and poor infrastructure being two of the main issues. Nineteen faculty members have quit AIIMS in the last five years. Of them, three professors did so in the last six months. About 10,000 patients come to AIIMS, the country’s premier healthcare facility every day.

It was a reality check for the 1,500-bed Safdarjung Hospital early this month when not a single doctor appeared for interviews scheduled to select assistant professors in its various super-speciality departments such as neurosurgery and nephrology. About 10,000 patients visit the top Central government hospital every day.

At Maulana Azad Medical College, 80 per cent seats for pre-clinical posts in post-graduation courses are vacant. “The government needs to have a recruitment policy that ensures all courses get adequate applicants who graduate as doctors in various departments,” says Dean Dr Siddharth Ramji.

The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India’s latest report highlights the problem. Last year, the Union Health Ministry also said that 1,595 posts of doctors were vacant in Delhi’s top government hospitals, including AIIMS, Safdarjung Hospital, RML Hospital and LHMC.

The situation elsewhere in the country is worse. India has seven doctors for every 10,000 people, half the global average, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). Data from the Indian Medical Association (IMA) shows the country needs more than 50,000 critical care specialists, but has just 8,350.

Faculty recruitment

The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) is responsible for the recruitment of regular doctors at hospitals run by both the Delhi government as well as the Centre. Hospitals themselves hire ad-hoc and contractual doctors. Experts say the UPSC’s recruitment process is tedious. From advertisements about vacancies to final interviews, the commission spends years to hire a doctor, they say.

“By the time hirings are done, new vacancies crop up. And the cycle continues. Doctors are also tired of waiting endlessly, and, hence, they start looking for other options. The overall recruitment policy is to blame for the crisis in Delhi and other parts of the country,” says former IMA President Dr Vinay Aggarwal.

The Union government has not laid down guidelines regarding ad-hoc doctors, sources say. There are a large number of medical practitioners who have been working with hospitals on an ad-hoc basis for more than 20 years and still have not been made regular by the government.

“These doctors never get promotion or perks. They are working just to earn a living. If you join as an ad-hoc doctor, you will never become regular. Therefore, young doctors are now reluctant in taking up ad-hoc jobs” says Dr Aggarwal.

Perks over patients

Senior doctors who are now working with private hospitals feel that with changing times, medical practitioners want to have more money at an early stage.

“In the last 10 years, many new private hospitals came up all over the country. Doctors began to leave government organisations,” says Dr Anoop Mishra, chairman, Fortis C-Doc.

He left AIIMS in 2007 as a professor in the department of internal medicine. “Private institutions are providing great career options to doctors,” says Mishra, who had spent 30 years with AIIMS where he started his career as an undergraduate.

Also, for the younger generation, the wait of 11-12 years to get a job is no longer exciting. “We got students from Delhi schools talking about their future, and only five per cent wanted to become doctors. They did not want to wait for so long to get into the profession,” says Dr MP Sharma, head of gastroenterology at Rockland Hospital. Sharma left AIIMS in 2004. He was head of the gastro department.

Security concerns

In the last two years, as many as 55 cases of assault have been reported from seven Delhi government hospitals. Data provided by the Federation of Resident Doctors’ Association (FORDA) says that FIRs were registered in 31 cases, but in only one case the accused were held guilty. There has been no decision in other pending cases.

Taking suo moto cognizance of increasing incidents of violence against doctors in government hospitals, the Delhi High Court in May called for a status report from the Centre, the Delhi government, the IMA and the AIIMS Resident Doctors’ Association. A Bench of Acting Chief Justice Gita Mittal and Justice Anu Malhotra also directed the Centre and the Delhi government to furnish details of operationalisation of all public hospitals in Delhi as well as the increase in their patient load.

“There was a strike called on February 27, 2015. The Health Minister of Delhi and the Union Health Secretary promised for better security but nothing changed and more incidences of assaults followed. In June 2015, several letters were written to higher authorities regarding poor infrastructure and security issues,” says Dr Solanki.

Doctors allege that the government has been giving them false promises for more than two years now. “The Delhi Health Minister in agreement with the then L-G Najeeb Jung provided 500 home guards in hospitals. But the deployed guards stayed for only 15 days, and it was back to square one,” says Dr Solanki.

AIIMS in other cities

Six other AIIMS in the country are also facing an acute shortage of doctors and non-teaching staff. Of the 1,830 faculty posts, barely 583 (31 per cent) have been filled up. In each of the six premier institutions at Bhopal, Bhubaneswar, Jodhpur, Patna, Raipur, and Rishikesh, 305 posts have been sanctioned. The strength at Bhopal, Raipur and Patna is 60, 74 and 52, respectively. While there are up to 22,656 posts of non-teaching staff, only 3,862 appointments have been done, whereas 83 per cent posts are vacant. Even as the Union Health Ministry is under much strain to fill up posts at existing AIIMS units, four new centres at Andhra Pradesh (Rs 1,618 crore), West Bengal (Rs 1,754 crore), Maharashtra (Rs 1,577 crore) and Uttar Pradesh (Rs 1,011 crore) have been announced.

Steps taken

Union Health Minister JP Nadda informed the Rajya Sabha recently that a number of steps were being taken to meet the shortage of doctors in medical institutes. The ratio of teachers to students has been revised. The government has also enhanced the age limit for appointment, extension and re-employment of teachers, deans, principals and directors in medical colleges from 65 to 70 years. “As far as Central government hospitals are concerned, creation of new posts, including those of doctors, is a continuous process, and is taken up as per requirements and availability of resources,” he said.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

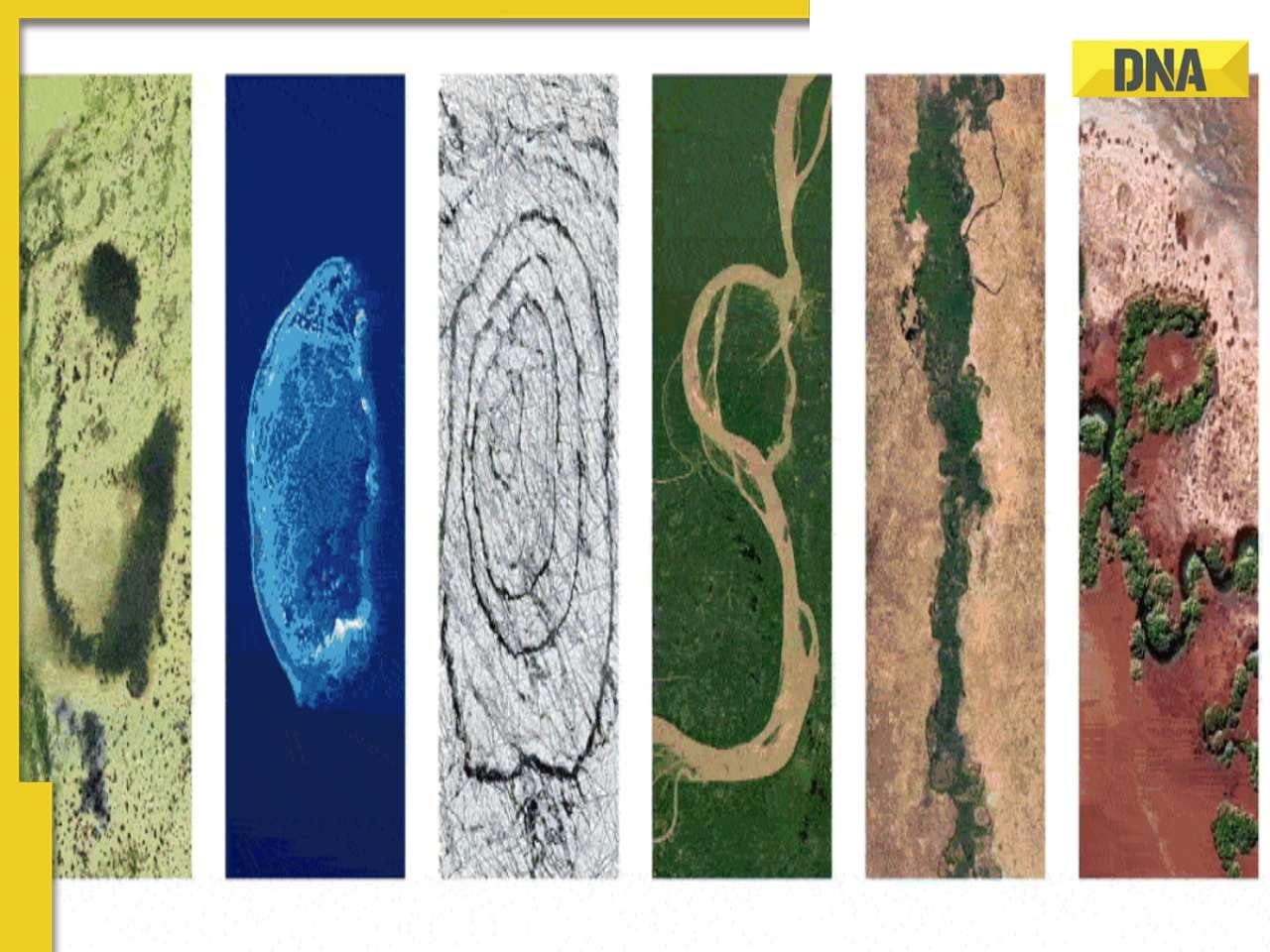

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)