Vasudha Dhagamwar, women’s activist, law professor and founder-member of MARG, says the years since the Mathura judgment are proof that a combination of factors prevents judges from ordering harsher sentences for rape convicts.

When four young law professors wrote an ‘Open Letter to the Chief Justice of India’ in 1979 following an acquittal in the landmark case of Mathura, a tribal girl who was raped, it served as a launchpad for a countrywide movement among women’s groups to demand gender sensitive amendments to the definition of rape, the issue of consent, the issue of the victim’s previous sexual relations and various investigative procedures in rape trials. Over three decades later, one of the authors of that historical Open Letter says little has changed by way of protecting a rape survivor’s dignity or ensuring justice is served.

Vasudha Dhagamwar, women’s activist, law professor and founder-member of MARG, says the years since the Mathura judgment are proof that a combination of factors prevents judges from ordering harsher sentences for rape convicts.

Calling the demand for chemical castration and death penalty for rapists a knee jerk one, Dhagamwar, who has done a considerable amount of research and writing on criminal law, says the priority should instead be on addressing societal biases and attitudes, and on reforms in police training and investigations.

“Why wasn’t there a morcha to Mahipalpur?” she asks, recollecting Amravati town of the 1970s when several eve-teasing incidents were being reported and the local Vanita Samaj had to acknowledge that the problem was with the town’s boys’ upbringing. “Track down the numbers of the cars that passed by and did not offer help,” she says.

Having held several workshops to train lower rung police personnel, Dhagamwar says the government’s announcement of seven women police constables and two woman sub-inspectors for every police station in the capital is little more than eyewash. “I have done some work with the Delhi Police and can tell you that for every vacancy advertised, there would be 25,000 male applicants and not more than 100 women. And those women would not even fulfil basic requirements such as height. Where will they suddenly find so many trained policewomen? They don’t spring out of the ground,” she says, adding that the judiciary shares the same plight, with thousands of undertrials languishing in jail awaiting trial.

Citing instances of women police constables sent for training when they were either four months pregnant or barely three months into post-partum recovery, Dhagamwar says the absence of communication between higher rung police officers and the footsoldiers is partly to blame. “We were holding a workshop for constables and the moment an officer walks in everybody goes silent. We ask how many police stations have a toilet and barely a hand goes up,” she continues. When policewomen work without separate toilets in police stations, with no place to change, rest or eat, it is natural for them to feel they lack respect within the force. “Women said they got no training. They were asked to sit in the chowky or sit in the car, just serving a decorative purpose.” The government’s assurance that urban police stations will have several times the women personnel they now do cannot be fulfilled for at least five years, she adds.

Even years after their Open Letter protested colonial, patriarchal ideas of what can be termed a woman’s consent, on whom the burden of proof should lie, acquittals continue, Dhagamwar says. “There is an unwillingness in the judiciary to give a higher sentence. Therefore we haven’t come very far on that count.”

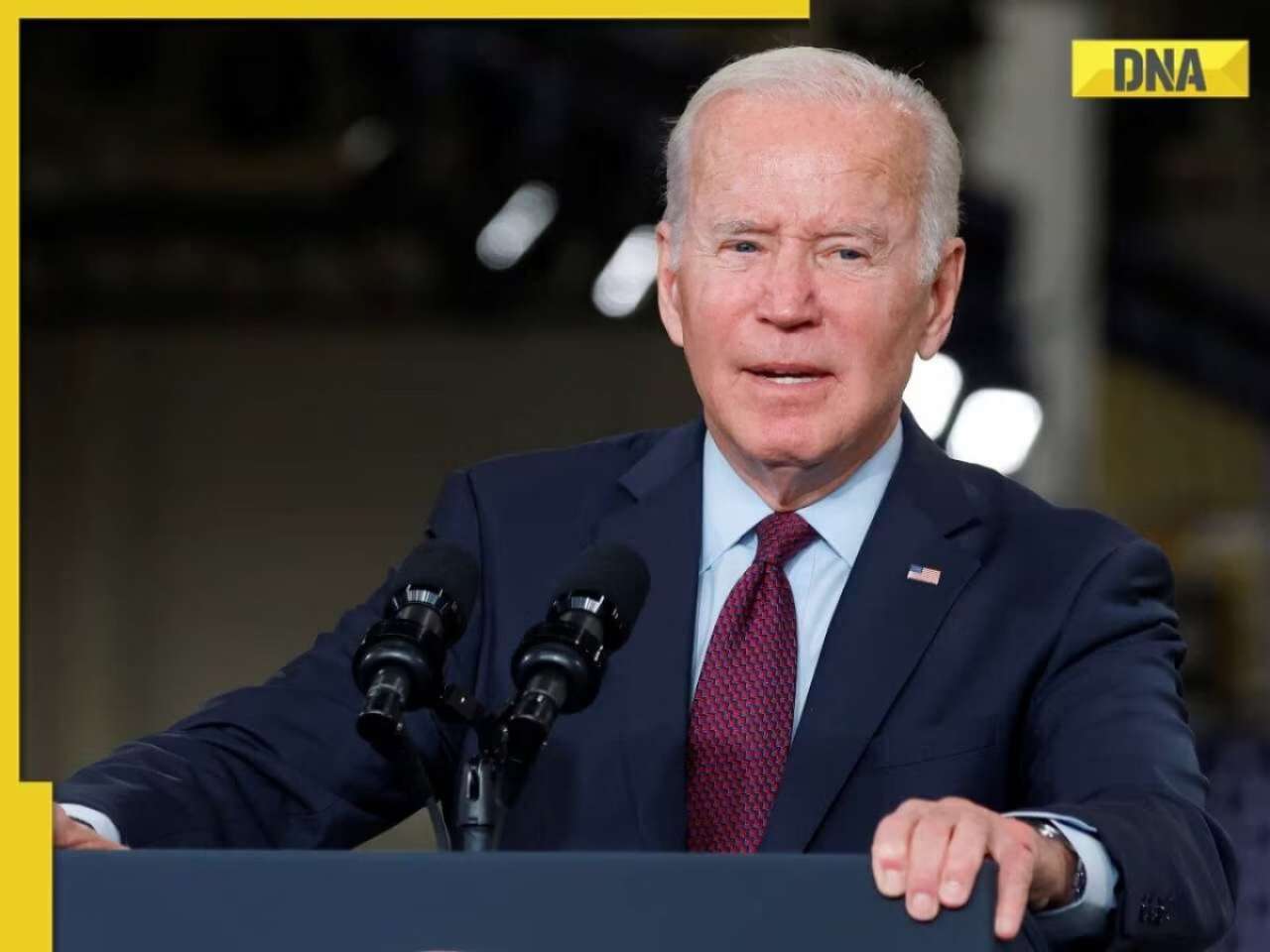

![submenu-img]() US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan

US imposes sanctions on Chinese, Belarus firms for providing ballistic missile tech to Pakistan![submenu-img]() 'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran

'Don't have any comment': White House mum on reports of Israeli strikes in Iran![submenu-img]() Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case

Yes Bank co-founder Rana Kapoor gets bail after four years in bank fraud case![submenu-img]() Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details

Barmer Lok Sabha Polls 2024: Check key candidates, date of voting and other important details![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore

This star once lived in garage, earned Rs 51 as first salary; now charges Rs 5 crore per film, is worth Rs 335 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth…

Meet actress, who worked as cook for free food, mopped floors, one Instagram post changed her life, is now worth… ![submenu-img]() UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name

UP man arrested for booking cab from Salman Khan's house under Lawrence Bishnoi's name ![submenu-img]() 'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family

'Justice milega': Ankita Lokhande talks about Sushant Singh Rajput, reveals she's still connected with his family![submenu-img]() Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'

Rajkummar Rao reacts to plastic surgery rumours, admits he got fillers: 'If something gives me confidence...'![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings

IPL 2024: KL Rahul, Quinton de Kock star in Lucknow Super Giants' dominating 8-wicket win over Chennai Super Kings![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits

Watch: Virat Kohli's cheeky 'your wife' remark to Dinesh Karthik leaves RCB teammates in splits ![submenu-img]() DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad

DC vs SRH IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() 'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013

'Kohli said it's not an option, just...': KL Rahul recalls his IPL debut for RCB in 2013![submenu-img]() Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft

Canada's biggest heist: Two Indian-origin men among six arrested for Rs 1300 crore cash, gold theft![submenu-img]() Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…

Donuru Ananya Reddy, who secured AIR 3 in UPSC CSE 2023, calls Virat Kohli her inspiration, says…![submenu-img]() Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…

Nestle getting children addicted to sugar, Cerelac contains 3 grams of sugar per serving in India but not in…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch

Viral video: Woman enters crowded Delhi bus wearing bikini, makes obscene gesture at passenger, watch![submenu-img]() This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

This Swiss Alps wedding outshine Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani's Jamnagar pre-wedding gala

)

)

)

)

)

)

)