He loved French cookbooks, invented a new way of making khichdi, and wrote long disquisitions on the comparative breakfast, lunch and dinner habits of the East and the West. Hindol Sengupta’s latest, The Modern Monk: What Vivekananda Means to us Today, shows that there was a lot more to Swami Vivekananda than the charismatic sanyasi who floored the West in 1893 with his address at the Parliament of World Religions. Edited excerpts from an email interview with Sengupta.

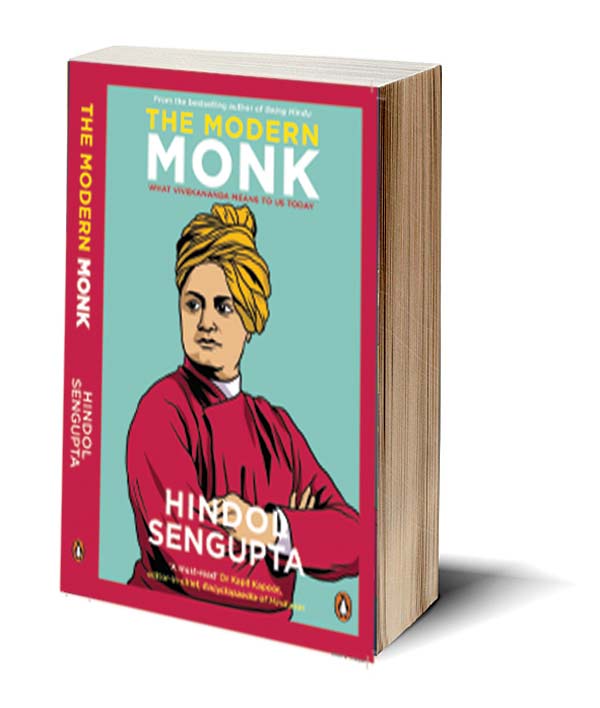

The Modern Monk is not a biography of Swami Vivekananda. It is an argument about why Vivekananda is relevant today. Vivekananda’s image is everywhere. There he stands, arms folded, challenging us with those luminous eyes to go beyond our patterns, our conditioning. And what we have done is exactly the opposite. We have made him a paper cut-out, one more idol. I am challenging the calendar art version of Vivekananda and presenting him in raw flesh and blood.

The arresting physical presence is one of the aspects of Vivekananda that makes him ‘cool’. He was someone who understood the power of appearances and knew how to use it to propagate his ideals. When he first arrived in America and was taken around in a carriage in his saffron robes and turban, he knew that many onlookers thought he was some raja. But he bore this quietly because he knew that to influence minds he had to grab their attention first.

There has been a heightened interest in the cultural attributes of India, among Indians and around the world. This is a by-product of India’s economic rise that, in post-colonial societies, always goes hand-in-hand with the end of the civilisational deracination these societies are infamous for. Though, in a sense, Vivekananda never went away — from Nehru to Modi, which prime minister has not praised him?

Unlike other religious orders, the appeal of the Ramkrishna Mission he set up has little appeal outside Bengal. The Ramakrishna Mission is one of the biggest global Hindu orders with new centres coming up all the time. The reason it seems limited is because they are extremely low key. They are a pure spiritual order, and highly intellectual. Only last year the man who won the Infosys Prize for Mathematics is Mahan Mj or as people within the Mission call him — Mahan Maharaj, a global expert in geometric group theory, low-dimensional topology and complex geometry. Mahan Mj is not alone. Also, the Mission seems quieter than others is because they don’t have one person or one living guru who embodies the message, and they are quite frugal.

Vivekananda is the most important figure in my life who is not alive. He is in everything that I do. My family for three generations has been devoted to the Mission. But rare is the Bengali who doesn’t have some connection with Ramakrishna Paramhansa, the spiritual master of Vivekananda, the Mission and Vivekananda himself.

Most certainly. I have no doubt that his success in the West won him many converts at home. I think Vivekananda knew that too and used it to his advantage. This is not so startling because Vivekananda saw around him a country ruled by colonial masters. Obviously in such a society the white man is seen as the master race, and their acceptance is craved, their example followed. Vivekananda was a nationalist and he took the battle to the lion’s den. He dared to fight the West on its own turf and won.

The most important tenet is civilisational literacy. Vivekananda instinctively understood that you must know where you come from to understand where you are going. He understood long before most other people that India’s degradation comes not just from foreign rulers but from its own leaders who, in thought and deed, were hardly Indian. He realised that a nation cannot build itself on borrowed ideas.