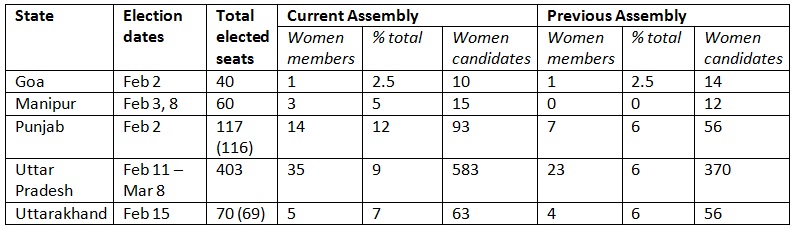

Election dates were announced for Legislative Assemblies in five states on January 4. They present an opportunity to change the gender politics of electoral democracy in those states.

A Constitution that places the Right to Equality above other fundamental rights is dishonoured by the pathetic representation of India’s largest minority— women. A Gender Equality Election Checklist prepared for the Tamil Nadu elections in May 2016 identified avenues where political parties could show their commitment to gender equality.

As they fight this round of Assembly elections, parties could begin to ameliorate this situation through two affirmative and two interdictory measures. The affirmative measures are gender parity in nominations and equal support to male and female candidates in the election campaign. The interdictory measures are to not nominate those who are guilty of misogynistic hate speech and those who have been charge-sheeted for sexual and gender-based violence.

We set up gender parity as an aspiration, but from where we now sit, it is a distant one. A good place to start the journey towards parity is with nominations. What would be ideal is to consistently make an effort to identify women with leadership potential and to groom them towards legislative careers, regardless of whether elections are imminent.

Where are these women to be found? To those who are looking, they are everywhere. It is our limited and circular definition of leadership that blocks our vision. We assume that it is when women (or men) occupy formal leadership positions that they are leaders. However, if we deconstruct leadership and consider the various skills and attributes that make up what is really just a rubric, it is clear that many individuals outside of the ranks of formal, high-profile, public sphere leadership positions, possess these qualities. What are these qualities? My off-the-cuff list of everyday leadership qualities would include vision (what could be, what should be), communication skills (the ability to share that vision), organisational skills (the ability to plan how to achieve that vision and the attention to detail that makes the plan realistic) and the ability to work with people. Integrity should be an indispensible addition to this list when we are speaking of public leadership, although, sadly, it is not.

Women who manage large joint families, in both rural and urban settings, are imagining individualised outcomes for members of their households as well as collective outcomes for the family. They balance budgets and make plans, and are willing to work towards those plans. They work with members (stakeholders) as well as service providers and vendors, seeking to maximise their return. They have to negotiate and they have to consider daily trade-offs, both with regard to stakeholders’ interests and resource use. They navigate difficult relationships within the immediate and extended family, without losing focus. If this is not leadership, what is? Whether men or women perform these roles in a family, they are leaders.

Similarly, those who volunteer with their housing society or neighbourhood watch group are gaining leadership experience. They may have initiated small projects, budgeted for them and supervised their execution. Those who work with NGOs show leadership at every level. For instance, if you worked at a sexual assault crisis centre, you would have a clear sense of justice and compassion to start with. But you would also be a great listener, someone who could analyse what she is hearing and chart a path to resolution and healing and, most important, someone who has learned to offer practical suggestions without imposing them— allowing your client to retain agency in their life. Is that not leadership?

In other words, leaders are everywhere if you start to look for them. Leaders also belong to every gender—if we are willing to embrace that idea. It should have been the work of party cadres to identify, celebrate and draw leaders in from across society, but if they have not done this work, those making nomination decisions may yet give them a chance to suggest women who have leadership qualities— perhaps even from the party rank and file? For example, the women who organised logistics during the last election rally in the district; the women who stepped up to gather and distribute food aid during the last round of communal riots or the women who organised anti-rape protests are all leaders.

The bottom line is a commitment to awarding at least half the party’s tickets in a state to women. Those women may be incumbent legislators, or members of the state-level party leadership, or district party organisers, or women who have gained experience at the Panchayat level thanks to the 73rd Amendment. They are already visible, already tested and already known to be willing to serve. Two decades down the line, there are enough of them that gender parity should not be difficult— we are probably spoiled for choice.

Nominating women is not enough. They need material and human support during the campaign. It is not enough for the party’s stellar campaigner to swing by their constituency, although that would raise their profile.

From time to time, in the years I have lived in this constituency, political parties have nominated women candidates in corporation and Assembly elections. I have never once set eyes on the candidate nor have they received a great deal of media attention. Some enthusiastic first-time candidates from small parties or independents, always men, are the ones who have rung our doorbell to introduce themselves. The women never come. I suspect that one reason for this is that their resources are over-extended.

Across the world, researchers have found that it is hard for women to raise funds for election campaigns. Patrilocal marriage (that is, when women get married and leave their homes for those of their husbands), their lack of ownership or access to capital, their smaller social and business networks and, as underworld elements become involved in politics, their relative lack of intimacy with this world inhibit their fundraising possibilities. They do not have money to spend on posters, on those three-wheelers that broadcast election slogans and speeches, on rally venues or possibly, even on chai-paani for campaign workers. There is so little transparency in campaign financing that we have no way of knowing how parties raise money or how they allocate it at election time. Making transparent and fair allocations would go a long way in making women candidates electable.

It is also how human resources get divided. Most of us do not know exactly how party workers are organised for campaigning but it seems likely that the most prominent and popular figures draw the largest pool of campaigners. It may be debated whether it is these campaigners who make them prominent or whether success breeds success. What need not be debated is whether women who are new to politics need that institutional support or not. If they are at all allocated, volunteers for canvassing votes may be allocated to women candidates on an equal basis as prominent male candidates.

Essentially, political party leaders need to signal to party cadres as well as the electorate that their female candidates are serious contenders, worthy of receiving attention and votes.

It is a very simple idea. You cannot represent the best interests of those whom you routinely disparage and objectify. Where around half the population of a constituency is female, or non-male, a politician or candidate who regards women as less than human cannot possibly speak for their rights and interests.

Hate speech against women is such a commonplace trait of male politicians in India that a casual Google search yielded practically a page of listicles of 10-12-20 worst misogynistic utterances. There was evidently enough data to mine many a top-ten list! Many of those featuring on these lists are from the states going to the polls in the next three months, and the Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are major offenders (though no one is exempt). The founder of the SP features on several of these lists and so we cannot expect him to find fault with misogyny but can we hope that at least the BJP will pretend this matters to them?

Denying those who make statements that dehumanise women (for example, dismissing their work) or objectify them (for instance, describing their appearance) an election ticket would send a strong message from any party leadership that such thinking and, therefore, such speech was not acceptable. Moreover, it would indicate that such a party would respect women’s worth as humans and as citizens and be unlikely to infringe on their rights.

But who will bell the cat? Every party has speech offenders and even parties headed by women hesitate to rock the boat and call them on their offensive attitudes. Therefore, in our election checklist, we also asked voters not to vote for such parties— but who would be left standing? Faced with five state elections, the question for us should be— will we get them to stop? This is one article, but can we mirror this in a hundred thousand fora and get parties to take cognizance of this offence?

If, for reasons of political wheeling-dealing and favours owed to each other, excluding speech offenders is not possible, perhaps we can advocate a speech code that lays down what is acceptable and what is not, at least when someone is speaking on a party platform. That will still tell us what the party stands for and there is the dim hope that people who fake it, will someday make it to an attitudinal overhaul.

Innocent, until proven guilty, and given how long our courts take, this is a tough one to implement, I admit. But, if it seems wrong to make a person pay for unproven charges, think of the message we send when we back those charged— and possibly guilty. For the same reason that the courts take so long, they could have a full career in politics, pontificating to others about morality, law and order, while in fact, still facing charges. This is also impunity.

Perhaps unrealistic, but it is important for our legislators to be beyond reproach. Those who speak for us and who will make laws that regulate our behaviour must also exemplify some minimum moral standards— and to not be facing charges for sexual and gender-based violence constitute, to my mind, that bare minimum. How can someone accused of sexual harassment, molestation, rape or torture uphold a Constitution which sanctifies the right to equality and the right to life?

In our society, in spite of our newly minted outrage when rape or sexual harassment is reported in public spaces, we still consider sexual and gender-based violence within homes and relationships a minor offence— a ladies’ problem, just slightly embarrassing to talk about in decent company. When charges of harassment, molestation or rape are made or even when cruelty, domestic violence or dowry charges are filed, unequivocal, zero-tolerance positions are hard to advocate. We wonder about false charges, especially if the accused is powerful. We think that maybe someone is making a mountain out of a molehill. This is explicable given the tight web of extended family relationships that anchors most of our lives, but it is not excusable by any means.

Political parties that favour the bully on a host of social issues must lead by example to confront the ubiquitous culture of impunity for sexual and gender-based violence. And there is no better time to do it than right before an election.

Every election is an opportunity for political parties to re-invent themselves. They are lucky that public memory is fairly short-lived. This is an opening for parties to position themselves as advocates of gender equality and women’s empowerment. These are states where this could make a difference. Safety is not about protection and castration, but about genuine respect for human rights and good governance that ends impunity. Will the major political parties in the fray in Goa, Manipur, Punjab, Uttarakhand and UP avail of this opportunity? Highly unlikely.

Equally important to me is whether we, as citizens, activists and media, will take the opportunity to put gender equality on the election agenda. This is also our opportunity to let politicians know that this matters to us. For a brief moment, they need us and say they want to know what we think. They need the attention and endorsement of the media. They need to get through their campaigns unchallenged by lawyers and activists. They need our votes. We’ve got them paying attention and should speak our mind without wasting time.

Swarna Rajagopalan is a political scientist by training. She is also the founder of Prajnya. The Prajnya Gender Equality Election Checklist offers parties and voters a short list of do’s and don’ts in the run-up to elections.