With Red Fort recently being adopted by Dalmia group as part of a government initiative, DNA looks at several other lost monuments in the Capital that cry for care to bring back their lost glory

Nestled in the cramped lanes of a densely populated Paharganj, lies a 14th century marvel, Qila Qadam Sharif, a tomb where Emperor Firuz Shah Tughlaq’s son rests in peace.

The Sultan had built it for himself but his son’s untimely death meant the prince found burial space here.

Lying in abject neglect, a huge fort-like structure stood tall here once. Today, it’s reduced to an open space amid the clutter where kids play cricket.

A market for manufacturing artificial leather commonly known as rexine is the landmark for those visiting this medieval monument.

Tughlaq’s son, Fateh Khan died in 1376, and the Sultan decided to bury him in the tomb. The sacred stone footprints of Prophet Muhammed brought from Mecca were safely placed in the Dargah.

This gave it the name Qadam (feet) Sharif.

Today, Qadam Sharif is merely a home to the family of Farid-ud-din, the Khadeem of the Dargah.

He claims lineage to the family entrusted with taking care of the dargah by the Sultan himself.

Other than the main dargah, the campus has a few more rooms where the family lives and runs a makeshift workshop, putting together ladies’ bags.

As he shows around, his two sons are busy putting together the bags that they sell in the market outside to run their home.

“The then Muttalawi, Haji Syed Shamshuddin Misri, was married to Tughlaq’s sister and was thus given the responsibility of maintaining this place. Our family has since lived here and we will not part with this ever. We have lived here for 13 to 14 generations now,” says Farid-ud-din who lives here with his wife, daughter and two sons.

The dargah is mostly close, receiving only a few visitors. During an occasional game of cricket inside the tomb, the shut door is converted into a target for the bowler to get the batsman out. In other words, the door that has remnants of royalty serves as the wicket or stumps.

At the main entrance of the campus, one is greeted by an old wooden gate with one panel missing.

“People in Delhi are not really aware about this place. It’s the foreign tourists who read about it and usually come here.”

Paharganj, adjoining the New Delhi Railway Station, is a centrally-located international tourist hub with hotels and lodges that suit all pockets making it a popular destination for long and short stays.

Wearing a grey kurta-pyjama, the Khadeem, in his mid 40s, proudly says he was born here.

Khadeem recalls the tales passed on to him by his forefathers and is nonchalant to the cracks on the dome. “When I was born there (pointing to a tiny room), huge rock-like structures jutted out from the roof and one had to literally crawl to enter the room.”

Qila Qadam Sharif was once a big site with massive gates, walls and a tomb space in the core.

Over the years, the whole area around Qadam Sharif has become a part of present day Paharganj known for its chaos and disorder.

The big walls that once donned the campus have now disappeared.

(Clockwise: 1. It is difficult to believe that once, the Masjid Kalu Sarai, was a sight to behold, 2. Qadam Sharif is now merely a home to a family, 3. Lying in abject neglect, a huge fort-like structure stood tall in Qadam once, 4. Qadam Sharif in yesteryears)

The annual ‘Urs’ is celebrated here on Prophet’s birthday when the slab with the footprints is taken out and immersed in water. This water is then served as offering to the devotees.

The family is reluctant to hand over the Dargah to either Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) or the Waqf Board. “Nobody has taken care of it for so long. What will they do now? All they will do is kabza (forceful possession)” says Farid-Ud-din.

Qadam Sharif is one among several monuments, a part of Delhi’s heritage, which have died a slow death over the years. Is adopting monuments the way forward?

Recently, Red Fort, a 17th-century world heritage site, was adopted by the Dalmia Bharat group, an Indian conglomerate which won the bid to adopt the iconic structure. While historians show concern over the adoption, the government cite maintenance of the monument the soul reason for the decision. Experts believe they are open to the idea of adoption, provided there is no interference with history.

Historians believe that preservation and conservation is technical work and should not be given to anyone else but ASI, while the cafeteria and other similar parts could be outsourced.

The adoption, however, gives Dalmia group the right to look after the operations and the maintenance of the site for five years. Under the project, it will construct, landscape, illuminate, and maintain activities related to provision and development of tourist amenities.

Some believe that if the adoption scheme had come earlier, we might have been successful in saving some of our heritage, which is now lost forever.

“Apart from the rich cultural heritage, these monuments and the antiquity associated with them are hard-cash for any economy. They bring us a lot of revenue,” said KK Muhammed, a renowned archaeologist and former regional director (North) of the ASI.

Muhammed says while adoption of these monuments is one option, it should have included experts as well.

Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, an activist, traces the beginning of the heritage erosion back to the Partition days.

“During Partition when people migrated, there were encroachments and a lot of our architecture got lost without much documentation. The legacy and the stories also got lost,” he says.

He is of the view that empowering the ASI is the way forward. Their annual budget is only Rs 5 crore for 174 protected monuments in the city.

Another important thing is to help make citizens aware of the rich cultural heritage.

“While adoption is a good idea, but it is not a new scheme. It has just been rebranded and relaunched. Many private schools are already adopting the rich heritage of this city,” he said.

Encroachments and illegal occupation have ruined these architectural wonders that barely exist in Delhi’s heritage now.

Monuments which are not of national importance are taken care of by the state’s archaeology department. These state departments do not have any budgets and thus are not able to do much.

Sohail Hashmi, a renowned historian, points out that the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) and the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) were asked to come up with the list of the remaining monuments, which are not listed by the state department. However, four decades later, they still have not come up with the list.

“This way we are giving open invitations for encroachments. If a monument has to be adopted, a committee of experts should be set to decide the technicalities of it,” he said.

One of the first lists of monuments was created by Maulvi Zafar Hasan, an archaeologist with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) that were worthy of preservation in 1916. It featured 1,317 buildings in the Capital, of which 174 are currently protected by the ASI.

In his book ‘Monuments of Delhi: Lasting Splendor of the Great Mughals and Others’, Hasan has listed all small and large structures that once existed in Delhi.

However, today, there is no clear official record of the heritage sites in Delhi as many have either ceased to exist or are nowhere close to their original avatar.

Before Hasan, Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan, a renowned reformer and educationist, wrote the first compilation of Delhi’s rich heritage in his book ‘Asar-us-Sanadid’ (or Athar-ud-Sanadid). Originally published in 1846 in Urdu language, the book is divided into four parts and records all of Delhi’s heritage.

Hijre ka Gumbad

Few would know about Hijre ka Gumbad that once existed in the lawns of India Gate, a war memorial and an iconic part of Delhi’s heritage built by the British. It was a protected monument back in 1916 when Zafar Hasan wrote his book.

Zafar Hasan’s book ‘Monuments of Delhi’ refers to the Hijre ka Gumbad as a dome, with two walls outside the building intersecting each other, a classic cruciform.

He says the dome and the arches were made of brick and a portion of the dome already fallen. It appears to have been a tomb, but there is no trace of any grave, Hasan aads in his book. If one is to belive Hasan, deterioration came early to Hijre ka Gumbad — as early as 1916.

Today, there is no sign of any such monument there.

Though there is no documentation of the story behind the Gumbad, heritage activists believe that it belonged to one of the castrated slave warriors.

It is present in Hasan’s listing from 1916. It is believed that when India Gate’s foundation stone was laid on February 10, 1921, the area was cleared out and that is when the Gumbad was demolished.

As per the historians, young 15-year-old boys were castrated and were sold to be trained as warriors. These slave-soldiers men made elite warriors and were famous for their skills and discipline in battle.

Mughals used these castrated men to guard the ‘Mughal Harem’ to protect the women in the harem.

While one activist says that some of these unsullied soldiers were given territories because of their extra-ordinary skills, another says the land was handed over to such soldiers as a substiture for salaries.

Today, the crowded C-hexagon aka the India Gate roundabout attracts busy men and women and tourists, but not even a single curious soul. Who would, after all, believe that there once existed a structure, just a century ago, dedicated to an eunuch?

Kalu Sarai Masjid

Just 500 meters from the Vijay Mandal Enclave in Kalu Sarai area of South Delhi, in the narrow bylanes of the area, lies a historical jewel that even the time has forgotten.

It is difficult to believe that once, the Masjid Kalu Sarai, was a sight to behold. Today, the government apathy has left the structure in a state of extreme disrepair.

The bigger problem, however, is the people who have settled in the mosque premises. Families from all over the country have lived in the mosque for decades, and subsequently, have done irreversible damage to the structure. They do not allow anyone to enter the premises to conduct a survey. Sources said the residents have kept dogs as pets specifically for the purpose of terrorising the visitors.

Two years ago, Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, one of the leading Islamic organisations in India, as part of its programme to reopen the closed mosques in Delhi, had visited the Kalu Sarai mosque. Their team was attacked by dogs.

The Feroz Shah Kotla tower

A painting by Thomas Daniells, a landscape painter in the 18th century who spent seven years in India painting the scenes of Delhi, a tower can be seen in the Firoz Shah Kotla Fort. This tower does not exist anymore. The fortress, now in a bad condition, was built by Firoz Shah Tughlaq and currently houses one of the Ashokan Pillars, Jami Masjid, and a Baoli. People come here for Thursday prayers.

Whoever said “Kyun mata-e-dil ke lut jaane ka koi gham kare, shahr-e-dilli mein to aise vaqiye hote rahe (Why should someone cry over a broken heart (dil lutna), such incidents are common in a city like Delhi)” was probably right.

![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...

Elon Musk's Tesla to fire more than 14000 employees, preparing company for...![submenu-img]() Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...

Meet man, who cracked UPSC exam, then quit IAS officer's post to become monk due to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…

Ola S1 X gets massive price cut, electric scooter price now starts at just Rs…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now

Remember Jibraan Khan? Shah Rukh's son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, who worked in Brahmastra; here’s how he looks now![submenu-img]() From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend

From Bade Miyan Chote Miyan to Aavesham: Indian movies to watch in theatres this weekend ![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Amar Singh Chamkila, Premalu, Fallout, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

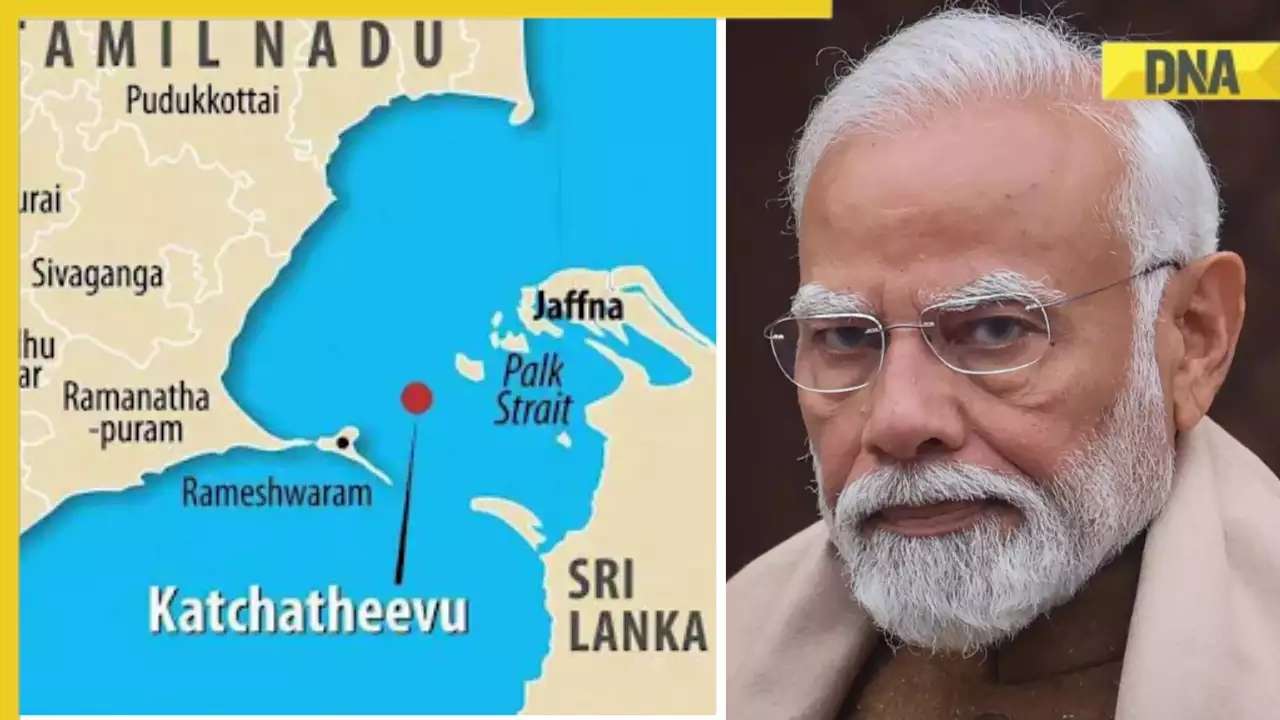

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?

What is Katchatheevu island row between India and Sri Lanka? Why it has resurfaced before Lok Sabha Elections 2024?![submenu-img]() Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...

Anushka Sharma, Virat Kohli officially reveal newborn son Akaay's face but only to...![submenu-img]() How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion

How Imtiaz Ali failed Amar Singh Chamkila, and why a good film can also be a bad biopic | Opinion![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'

Aamir Khan files FIR after video of him 'promoting particular party' circulates ahead of Lok Sabha elections: 'We are..'![submenu-img]() Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'

Henry Cavill and girlfriend Natalie Viscuso expecting their first child together, actor says 'I'm very excited'![submenu-img]() This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...

This actress was thrown out of films, insulted for her looks, now owns private jet, sea-facing bungalow worth Rs...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB

IPL 2024: Travis Head, Heinrich Klaasen power SRH to 25 run win over RCB![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

KKR vs RR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals

KKR vs RR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Kolkata Knight Riders vs Rajasthan Royals![submenu-img]() RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

RCB vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs

IPL 2024: Rohit Sharma's century goes in vain as CSK beat MI by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home

Watch viral video: Isha Ambani, Shloka Mehta, Anant Ambani spotted at Janhvi Kapoor's home![submenu-img]() This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...

This diety holds special significance for Mukesh Ambani, Nita Ambani, Isha Ambani, Akash, Anant , it is located in...![submenu-img]() Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video

Swiggy delivery partner steals Nike shoes kept outside flat, netizens react, watch viral video![submenu-img]() iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here

iPhone maker Apple warns users in India, other countries of this threat, know alert here![submenu-img]() Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

Old Digi Yatra app will not work at airports, know how to download new app

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)