While the film is titled Padmavati, there is more curiosity about this character played by Ranveer Singh

Ranveer Singh is playing the baddie in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmavati, and when his battle-scarred fierce look for Allauddin Khilji (called Khalji by some historians) was released on October 3, it created a social media storm. Apart from creating a Twitter tsunami of sorts, it has also brought the focus sharply back on the second and most powerful warmonger Sultan of the Khilji dynasty who ruled over the Delhi Sultanate which included a large swathe of the Indian subcontinent from 1296 to 1316.

Sach ka saamna

“Though I’m not privy to his filmmaking process, given SLB’s obsession with mixing mythology, legend and history with the grandiose (as we saw with Bajirao Mastani) it can be safely assumed that his latest too will be a lavish spectacle. I only wish filmmakers invested as much, if not more, in researching history than recreating the historical attire, jewellery or hairstyles of that era,” rues Kolkata-based socio-cultural historian Dr Meghana Kashyap.

Details that matter

She reveals that Allauddin was a treacherous and ruthless warmonger, who killed his own paternal uncle (who had raised him like a son after his father Shihabuddin Masood’s death) and dynasty-founder father-in-law Jalaluddin Khilji to become sultan of Delhi as is evidenced in the research by eminent late historian and Khilji dynasty expert K S Lal in his books, History of the Khaljis and Twilight of the Sultanate.

Dr Kashyap says, “He took on the Mongols and chased them right past current Afghanistan into Central Asia. His subjugation of Hindu kingdoms in Gujarat (plundered in 1299 and annexed in 1304 and one of the holiest Hindu shrines of Somnath was ransacked and desecrated), Ranthambore (1301), Chittor (1303), Malwa (1305), Siwana (1308), and Jalore (1311) need to be and I’m sure will be highlighted given that they blend in well with narrative, which sets him up as villain. Given the current socio-political mood in the country I will not be surprised to see it find many takers.”

Tell the truth!

Her views find an echo with historian and Head of Department of History at Birla College Professor Shailesh Shrivastav, who wonders if SLB’s latest will repeat the historical inaccuracies of his Peshwa period drama two years ago. “Bhansali created not only a meeting, but also a dance-off between the Peshwa’s wife Kashibai and his lover Mastani when they had not even met each other ever according to historical records of that time,” he laughs and adds, “I know the filmmakers will point out to the chartbuster of a song that became and Bajirao Mastani’s box office success of making Rs 355 crore plus to scotch out any room for that debate, but it feels terrible that the world’s largest film industry is incapable of making a truly well-researched historical. We can only envy Hollywood for its historicals and can only gape in horror if SLB decides to play to the gallery.”

Ratan and Padmavati

While an eye on collections pushes filmmakers into a hagiographic dazzle trap, the way passions run high with communities and sects over every little real or imagined slight is another problem admits Srivastava.

“There is no historical record to establish Padmavati (or Padmini as she’s also called in some folk traditions). The radiant beauty, who is kept captive by her own father Gandharv Sen who wants her to marry a man of his choice. She releases her talking parrot Hiraman, who carries her litany of woes to Chittor in current Rajasthan. So moved is the ruler Rawal Ratan Singh that he sets forth on a journey guided by the same parrot to the island nation in the South to marry her,” he points out and explains, “Mind you this entire tale is based on an epic poem written by Awadhi poet Malik Mohammed Jayasi in 1540 almost 250 years after Rawal Ratan Singh’s demise.”

Fictional story?

None of the contemporary historians from Alauddin Khilji’s time even make a passing reference to the queen of Chittor while mentioning the conquest of the fort. From the early 16th century, there was a mushrooming of adaptations in various languages which added and removed elements based on their regional audiences. Over a dozen such adaptations appeared in Persian and Urdu till 19th century based on Jayasi’s work points out Dr Kashyap who underlines, “It was Rajput balladeer’s Hemratan’s 1589 composition Gora Badal Padmini Chaupai which has gained maximum popularity given the oral tradition.”

Love and war

According to her, the intense hatred for the Muslim invader made these versions dwell far lesser on the love, courtship and marriage of Rawal Ratan Singh and Padmavati and more on the honour with which they fought and died fighting against Allauddin Khilji. “British Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod of the British East India Company who heard the tale from musician-balladeers mentioned the legend in his Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. From there it did not take long to travel to the then capital of British India, Calcutta, spawning a series of Bengali versions. It is interesting to see how by then it had become story of a pious, chaste Hindu beauty who thwarts the unwelcome lustful advances of a Muslim invader by immolating herself.”

He wasn’t all bad

Both Kashyap and Srivastav warn against using modern yardsticks of political correctness to look at Khilji. “It is impossible to condone or justify what Khilji did. But we need to remember that those were warlike times and this was not seen as abnormal and wrong,” says Shrivastav. “While he may have been merciless with anyone challenging his suzerainty, he was also an equally able administrator and took care of his subjects well. His price control policy, under which food grains, clothing, medicines, cattle, horses, etc were sold at fixed prices, preferably low, at various markets in Delhi, made him popular with both civilians and soldiers.”

His two marriages

Alauddin entered a consanguineous marriage with Jalaluddin’s elder daughter Mallika-e-Jahan who, the ancient historian Haji-ud-Dabir calls temperamental and vain as she tried to dominate Alauddin leading to friction. To make matters worse, he decided to take on a second wife Mahru, the daughter of his brother-in-law.

Khilji’s bachabazi

Well-known author, columnist and expert of religion culture and sexuality Devdutt Pattanaik has alluded in the past to Allauddin’s fascination for bachabazi (the taking on of young boys as sex slaves, a practice still found common in Pakistan and Afghanistan). A very young Malik Kafur (who was originally Hindu or Ethiopian) was captured from the port city of Khambhat by Allauddin’s general Nusrat Khan, during the 1299 invasion of Gujarat and gifted to the Sultan. “So mesmerised was Allauddin by the boy’s beauty that he kept him for himself till his death. Given his closeness to the Sultan, he rose in the ranks to become a leading warrior who Allauddin came to depend heavily on, even letting him lead several expeditions in the South to advance his kingdom in peninsular India,” says Shrivastav.

Rise of the male lover

By 1314, Alauddin became very distrustful of everyone around except his family and slaves. Several experienced administrators were sacked, the office of wazir (prime minister) was discontinued, and even had minister Sharaf Qa’ini executed on advice from Malik Kafur, who considered these officers as his rivals and a threat. In a year when the sultan turned critical, Malik Kafur was given all executive powers and made the Naib of the sultanate. The deep emotional bond between the duo did not go unnoticed. Chronicler of those times, Ziauddin Barani (1285–1357) states: “In those four or five years when the Sultan was losing his memory and senses, he had fallen deeply and madly in love with the Malik Naib. He had entrusted the responsibility of the government and the control of the servants to this useless, ungrateful, ingratiate, sodomite.”

What’s normal?

This aspect of Allauddin Khilji’s life and how it will be depicted has generated a lot of buzz in the LGBTQIA community who hope SLB will not shy from showing the truth. Equal rights activist Harish Iyer who works for the rights of the LGBT community, women, children and animals says he found the bigotry, exclusion and homophobia of the language used to attack SLB abominable. “Why should Khilji’s bisexuality or his relationship with his male lover Malik Kafur be linked to his ruthlessness? What is with these labels of alleged ‘sexual deviance?’ Anyways ‘normal’ is also a stereotype. So, can we stop using that word to describe heterosexual people, given how it implies people of other sexualities are abnormal?”

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

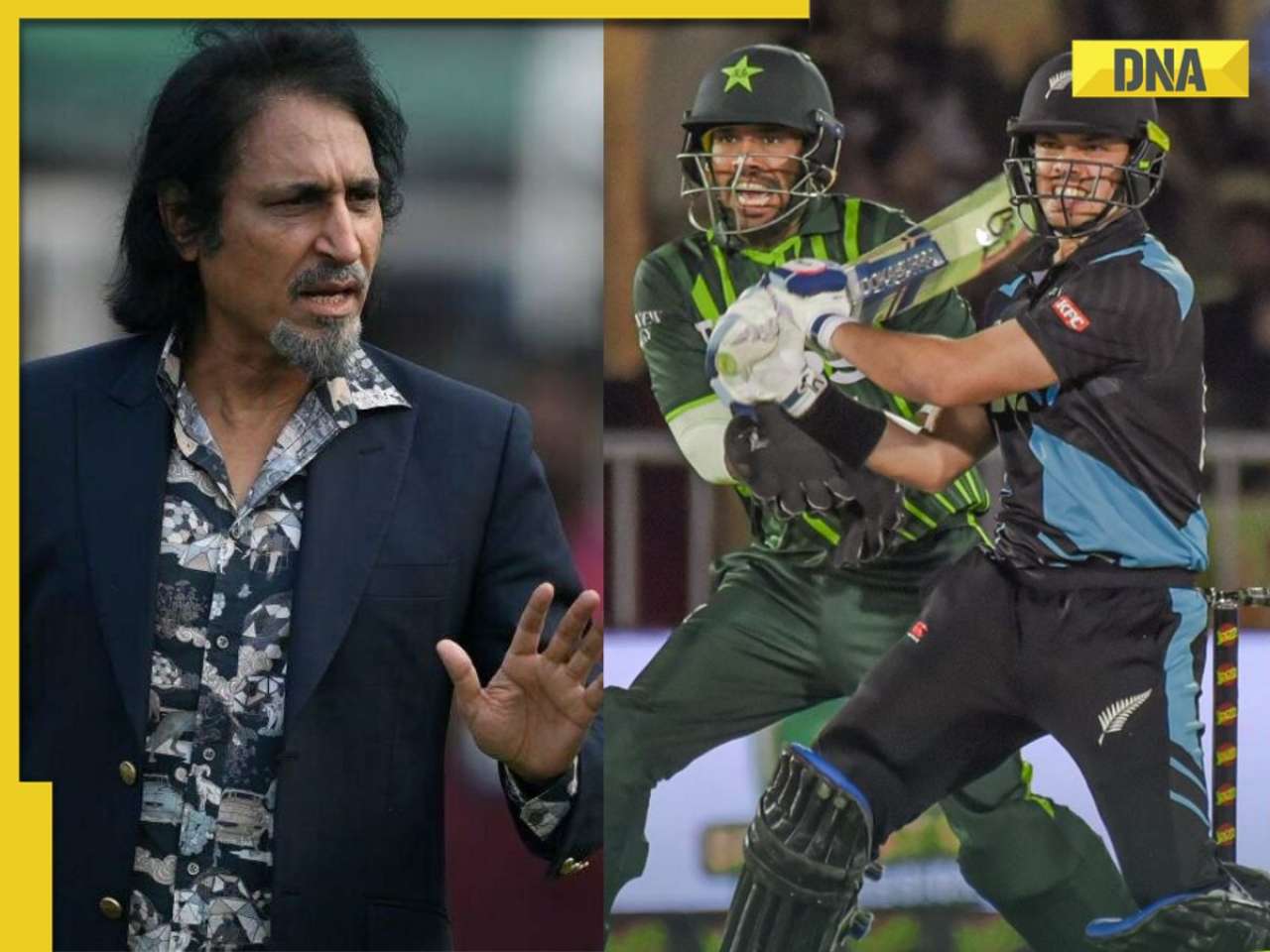

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

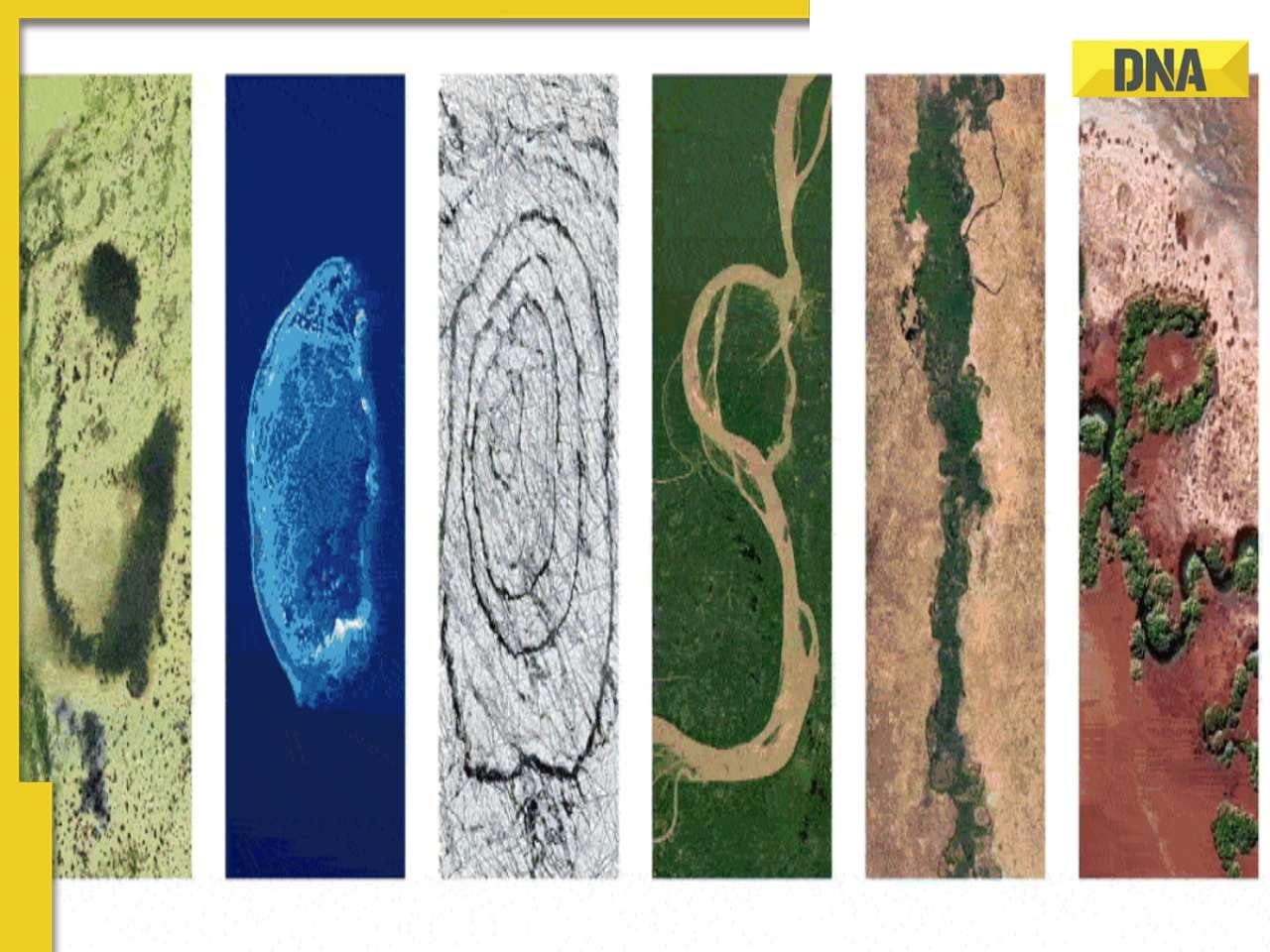

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)