On 14 May, the Supreme Court stayed the Arvind Kejriwal government's circular which demanded complete obeisance from the media as well as the public, even from the aam aadmi denizen of Delhi, whose cause he so zealously champions. The policy, discussed and debated in and by the media, criminalised any form of dissent or criticism of the public acts of the Delhi government, its ministers and other functionaries.

The stay was granted on the plea of lawyer Amit Sibal, Congress heavyweight Kapil Sibal's son.

It's true that this 6 May circular - F.No. 36/1/Policy/2015 was occasioned by what Kejriwal and his followers allege to be a 'supaari job' against him by the media. Such was the resentment that on 11 May, in a Google Hangout chat with AAP volunteers, the Chief Minister of Delhi, throwing all precautions and constitutional propriety to the wind, even promised that the government would "help" those "good people" in the media who are disgruntled with the state of affairs.

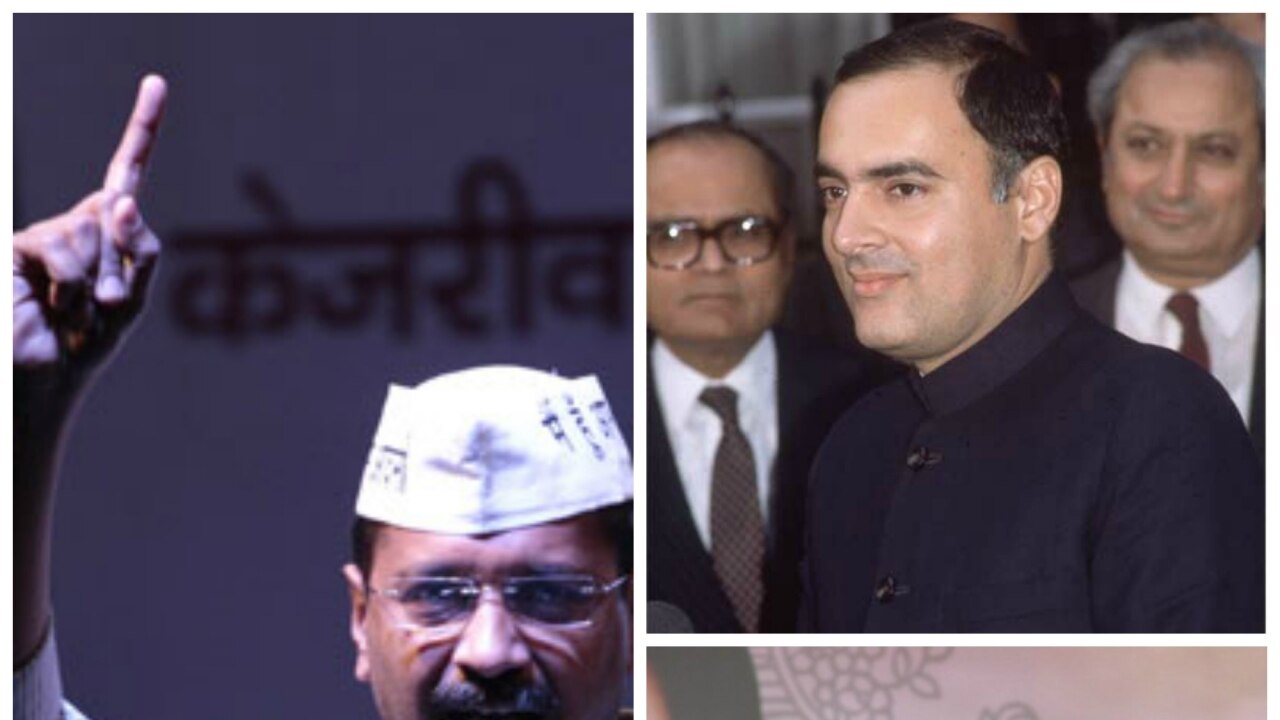

In hallowed company

To be honest, although the media could be perceived to be harsh in its constant scrutiny of Kejriwal and his party's politics and policies, to allege partiality and vindictiveness, is profoundly undemocratic and expressive of an attitude which abhors accountability.

And although the Congress was quick to seize the opportunity and shower abundant criticism, it ended up demonstrating its opportunistic streak, because Kejriwal's actions were not much different from those of Rajiv Gandhi in 1987-88.

When Rajiv was the PM and the Bofors kickbacks scam broke, he lost no time in going hammer and tongs at The Indian Express which relentlessly snapped at his heels, demanding answers. Other newspapers also jumped in, prompting him to introduce the Defamation Bill. This proposed legislation had the potential to render impossible any kind of investigative, even political journalism.

Any criticism of the government and its honchos could be termed "scurrilous" and slapped with criminal defamation charges. The most egregious provision was the one which put the burden on the media house or paper to prove that not only were the contents of the report true, but also that they were in public interest. The government and the ruling party had the sole and exclusive privilege to determine if this diktat had been complied with.

On 6 September 1988, all newspapers went on a day's strike in protest and soon, even senior party leaders were voicing their vocal opposition. So severe was the blowback that on 22 September Rajiv, who had resolutely asserted that the bill was in public interest, had to eat a humble pie by withdrawing the bill, accompanied by a press statement in which the government emphasised its commitment to protect and uphold the freedom of the press.

Then in 1997 it was the turn of EK Nayanar, Kerala's Marxist CM, to show his opposition to criticism. His Left Democratic Front government issued a circular in March that year, which forbade issuing of advertisements to those papers which published defamatory, "highly objectionable and obscene" articles against government servants and party workers. The small papers, which were at the forefront of criticising the government's corruption, were hit the hardest, till the government, browbeaten by the opposition, was forced to withdraw the circular some months later.

But Jayalalithaa has to be the "mother" of bludgeoning the media with criminal defamation charges. In 1994, she went on the offensive against RR Gopal's daily Nakkeeran, which was taking its vow of exposing her government's misdeeds quite seriously. Gopal was hounded and slapped with charges of defamation and violation of privacy. He moved the Supreme Court which on 7 October 1994 ruled emphatically in his favour. Justice Jeevan Reddy held that the Tamil Nadu government's actions smacked of mala fide and arbitrariness. He also held that government servants and public officials, the chief minister included, had no legal right to sue for defamation if the actions questioned, or even pilloried, were in the domain of the public functions they were supposed to discharge. And, so long as the criticism had a factual basis, reporters and journalists were immune from penal legal action and persecution.

Whether Kejriwal moves for the stay to be lifted remains to be seen, but it is clear that even though he claims to be "post-ideological", he shares the all-too-common ideology of demagogues to brook no criticism.