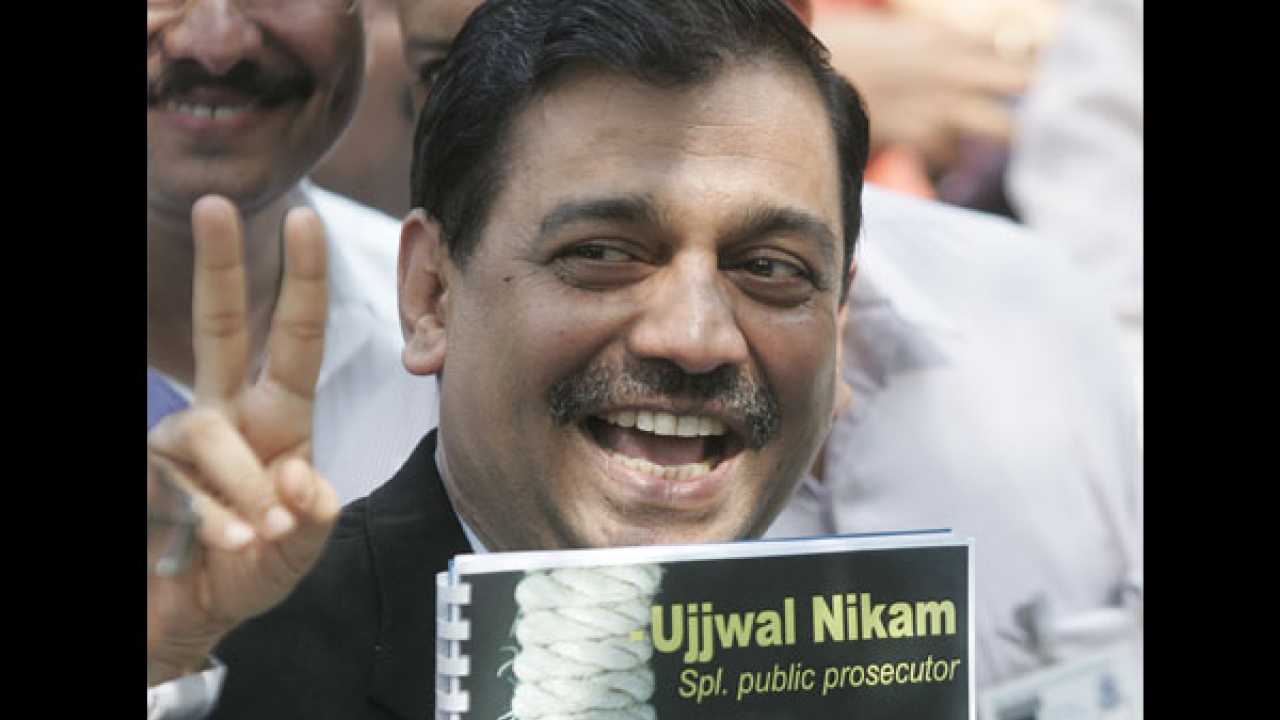

Ujjwal Nikam’s sensational “confession” has the potential to leave one oscillating between indignation and bewilderment. The Special Public Prosecutor, renowned, reviled, feted and infamous - all in equal measure, for his performance in high octane terror trials, claims to have fabricated evidence in order to sway public opinion against Ajmal Kasab. This brazen illegality by a lawyer, supposed to be “an officer of the court”, who by virtue of being a public prosecutor is vested with the responsibility of being a “minister of justice” and tasked with acting in utmost fairness to the rights of an accused, is bound to make one seethe with rage and explore legal options to justifiably penalise him. But a look at the reports from the archives- those on the trial proceedings, leaves one confused because they unequivocally rubbish Nikam’s belated confession. Quoting policemen and jail authorities, they state that Kasab was indeed being served non-vegetarian food and some variant of biryani.

The meaning and implication of this is clear- Nikam had the media eating out of his hands. The wily veteran of 38 capital sentences and 600 life terms, adept at grandstanding (quite often, quite bellicose) before the television cameras, delivered a virtuoso performance – he beguiled even seasoned journalists, already caught in the throes of what was a continuing national engrossment for four years, into being cavalier about facts. Only a negligible few were alert and responsible enough to put his claims and declarations through a rigorous fact-check. Did Nikam’s manipulative histrionics rock the boat of judicial impartiality? Justice (Retd.) SN Dhingra, one of the protagonists in another high profile case- that of Afzal guru, convicted and executed for the Parliament Attack, lost no time in issuing a quick denial. No stranger to criticism for presiding over and being carried away by the prosecution’s jingoism in what was the first 'mediatised' terror trial, Dhingra contended that judges resolutely brush aside the media’s speculation. That assertion remains one of dubious veracity, given that on 12 March, the Delhi High Court candidly admitted to the opposite and the Law Commission of India in its 200th Report (2006) said pretty much the same thing.

Dead men tell no tales, so we would never know for sure whether Kasab really had even an iota of remorse, or had Nikam not resorted to deplorable mendacity, would the judges have spared him the noose. But one thing is certain- that the events here prove the existence of a sharp conflict between a press freedom, fair trial, and, a lawyers’ right to express himself before the media. At first blush, this third right might seem a tad anachronistic, given the duties of a prosecutor and the fact that Kasab’s lawyers were mostly at the receiving end of the media and public’s opinion. However, if one thinks of a situation where both sides embark on full-scale media war (and such situations are neither uncommon nor unlikely to recur), this right assumes critical importance.

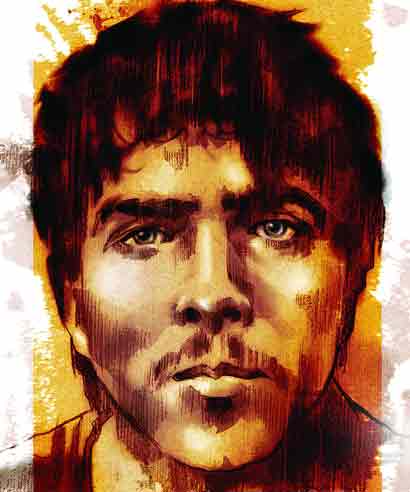

Ajmal Kasab / dna

At the very outset, it must be stated that no single party - the bar, the bench, and the fourth estate, can be singled out for charges of wrongdoing; the blame for a free and fair trial getting derailed has to be jointly shared. Also, the resolution of this conflict should not be enforced through the vehicle of the judiciary’s contempt power.

As things stand, Indian law - legislative provisions and judicial pronouncements - are not up to the task of striking a fair and effective balance. The Advocates Act and the Code of Criminal Procedure, along with a handful of higher judiciary rulings do provide some guiding principles, but they don’t go far enough to put in place an enforceable canon of ethics to regulate the prosecution and defence’s interactions with the media. The media’s periodic promises of enforcing self-regulation have never materialised, and the judiciary continues to remain tightly seated on its high-horse of imperturbable infallibility.

Therefore, it is to the United States one must turn. It was in 1963 that the Warren Commission, tasked with investigating and doing something about the fervid speculation around JFK’s assassination, pushed the American Bar Association to establish a committee which could lay down guidelines for regulating media coverage of criminal trials. Headed by Justice Paul C. Reardon, the Advisory Committee on Fair Trial and Free Press submitted its report in 1964, which addressed how lawyers (of both sides) should release information to the media, and how the law enforcement machinery- prosecutors, judges and the police, ought to conduct themselves. The recommendations of the Reardon Commission were subsequently integrated into the ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct (1995). These Rules are binding, and Rule 3.6 is germane to the present case. It prohibits both the prosecutor and defence counsel from making public commentary when he knows, or should know, that the information and statements given to the media would have a substantial likelihood of materially prejudicing a pending or ongoing proceeding. The framers of this Rule were sagacious enough to leave out an exception, otherwise the media would have been completely, and unconstitutionally barred from reporting on criminal trials. This “public record exception” provided enough space for briefing the media, so long as the statements were based on records submitted to the court and in public domain. It doesn’t confine one to cold facts, rather, it allows both sides to tell and explain their story, but without indulging in speculation, fiction, or deliberate attempts to mislead the court and subvert justice. And as the US Supreme Court’s decision in Gentile (1991) demonstrates, this worked quite well. Soon after his client was arrested and indicted for criminal charges, Gentile called a press conference in which he dissected the charges filed, and based upon that, excoriated the police and prosecution, labelling them a cabal of vindictive crooks. The State of Nevada contended that this broadside detrimentally affected its right and power to enforce criminal justice, and hence, the Nevada bar hauled up Gentile for professional misconduct. On appeal, the Supreme Court quashed the disciplinary proceedings, holding that even if criticism is withering and savage, it is legal so long as it is grounded in facts.

What happens when prosecutors go on a vicious slander campaign, like Nikam did? In his submissions before the court, he showered Kasab with epithets and painted him as a beastly creature undeserving of any clemency. One could look at US District Judge Kurt Engelhardt’s ruling in New Orleans’ Danziger case of 2013. Five police officers were convicted for shooting and killing unarmed civilians in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. It later came out that while the trial was going on, the prosecutors meticulously vilified the accused on the pages and website of the most widely read local newspaper. They were careful enough to do it in the garb of anonymity, and as a consequence, the jury, easily swayed, returned a guilty verdict. Engelhardt overturned the convictions and imposed stiff penalties on the prosecutors who by their “inflammatory invectives, accusatory screeds and vitriolic condemnations, created a carnivalesque atmosphere in which justice was distorted and perverted.”

Kasab is dead and buried, and Nikam is yet to show sincere regret. But all the three stakeholders must pull out all stops to put in place a mechanism which can avert the next mistrial.