An allocation of Rs 17,700 crore in the 2013-2014 Union Budget but not a single accountable rupee spent for pre-school education or a plate of food for the homeless children in Mumbai. Yoshita Sengupta investigates the absence of homeless children from ICDS registers

In 2010, Ms. Rekha, a homeless woman living on the footpath in Mumbai in her last month of pregnancy, slipped while trying to cross a wall. She was trying to get to a secluded spot, where she could have a bath without having men letch and pass lewd comments at her. The nearest public toilet was a 15-minute walk away. Her father Ramu, rushed to borrow money from a private lender to pay the bills at the private clinic to which Rekha was rushed by other members of the family. The doctor saved both the child and mother. Her family, which includes Ramu, brother Manohar, mother Basanti, sisters Agar and Pooja and her husband, all of whom live on the same street and make bamboo baskets for a living, were overjoyed. Within two months, the baby girl died.

She has a quick bath, with trains moving past and men staring at her. But, they are too far away to be dangerous and for her to hear their comments.

She has a quick bath, with trains moving past and men staring at her. But, they are too far away to be dangerous and for her to hear their comments.

In July 2012, Rekha gave birth to another girl. The family took the baby to a temple to pray for her healthy life and named her Chinmayee. On November 24, Chinmayee contracted fever. The family took her to a private clinic in Dharavi and the general physician prescribed her some medication. Ramu once again, borrowed money to buy expensive medicines from the pharmacy. The next two days, the child, in her discomfort, would cry through the night and Rekha would stay up taking care of her. The night of November 26, Rekha sleep well. Chinmanyee didn’t cry or wake anybody up. Rekha thought the medicines were finally working. Early morning on November 27, when Rekha tried to lift Chinmayee from the make-shift crib, the baby didn’t move or make a sound. The five-month-old had passed away in her sleep, nobody knows at what time.

She belongs to community that weaves bamboo baskets for a living. Occasionally, she helps the men in the family.

Rekha slipped into a state of shock, so did her husband. Ramu rushed Chinmayee to the physician, who confirmed the death. Ramu requested the doctor to write a letter stating the child had died due to an illness, a letter that authorities at the cremation ground would require to allow the family to complete the last rites. The doctor refused. “He first resisted and later said that he ran out of stationary, so I should go some place else. He was probably scared that he may fall into trouble because the baby died due to the medication that he had prescribed,” says Ramu.

Ramu then went to another doctor and requested him to issue a letter stating that the baby died a natural death. “That doctor asked for Rs 1,000 to issue the letter. Somehow, I managed to get the money and the child was taken to the crematorium,” he recalls. The family later found that the prescribed medicines were for adults and too strong for a baby. The doctor continues to practice. Rekha, a month after the incident, conceived again.

Rekha waits at ‘home’ for the men of her family, who after making some money during the day go to the local market to buy food grains that she will cook for a late dinner.

In the 2011-2012 financial budget, the time Rekha lost her second child, the Government of India allocated Rs 9,294 crore (around USD 1.5 billion) to the

Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme that is implemented by States across the country. On paper, the scheme provides supplementary nutrition, immunisation, health check-ups, and referral services to children below six years of age, expecting and nursing mothers. The scheme also offers non-formal pre-school education to children in the age group of three to six, and health and nutrition education to women in the age group of 15-45. On March 8 this year, Minister for Women and Child Development Krishna Tirath in a written reply to the Lok Sabha, submitted that in the financial year 2011-2012, the central government released a little over Rs 762.25 crore to Maharashtra to implement the ICDS scheme. The State added Rs 197 crore and spent a little over Rs 959 crore on the scheme.

However, Rekha, despite living in Mahim, bang in the centre of the State’s capital, is not a beneficiary of the ICDS scheme. In fact, she, and others in her 130-member strong community, isn’t even aware that the government allocates thousands of crores to stop incidents of child mortality and malnutrition, something she has faced twice in three years.

But the community in Mahim isn’t the only one with no access to the ICDS benefits in Mumbai. Homeless across the city are as clueless and the ones, who have been made aware of the scheme by social workers and Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), are not given access to the scheme by the implementing authorities.

In August 2012, a social worker, with a fellowship from non-profit organisation

Indo-Global Social Service Society, who has been working with the homeless in Mumbai for over 10 years, Shahikant Bhalerao noted names of children below the age of six in the 300-member strong homeless community in Ramabai area of Ghatkopar and the 100-member strong community of homeless, who live under the Amar Mahal flyover in the central suburbs of Mumbai. With names of 22 children from the Ramabai and eight from Amar Mahal, Bhalerao started looking for ICDS centres in both the areas.

Government officials made him run from one office to another and finally a few days later he managed to get the addresses of anganwadi (ICDS) centres the children of the two communities could be enrolled in. He made a formal list with names of children and their age and submitted it to the Anganwadi Centres (AWC). At first, the Anganwadi Workers (AWW) at both the centres refused to accept the request claiming the centres were running to full capacity. After Bhalerao argued, saying the government rule stated that AWC should have a minimum of 40 registered children but there was no prescribed upper limit, the AWWs allowed the children.

A few weeks later, when Bhalerao went to the communities to inquire if the children were regularly getting food and being taught, the families told him the children had stopped going to the centre because the AWWs didn’t treat them well, called them dirty and refused to let them enter the centres, saying that the parents of other children, who come from a slum nearby, would not want their children to interact with homeless kids.

When Bhalerao went to the centres and asked the AWWs why the kids were denied entry and why they weren’t officially registered into the scheme, they said their supervisors’ refused permission to enrol the children since they live on the other side of the road and not in the slum in which the AWC was located. On August 21, when this writer visited anganwadi No. 119 near Amar Mahal and asked the AWW why the homeless children were not being extended the benefits of the ICDS scheme, she said, “We haven’t gone to the community. We have been told to only give food to whoever crosses the road and comes to us. When we were given a workshop, the officials told us that we are not supposed to cross the road. We don’t have any problems (registering them) but we have a lot of work and we are supposed to work with the slum communities that we survey. We have NGOs bringing in children and women from homeless communities but until we get a go-ahead from our officers, we can’t do anything. We have passed on the details (to the supervisors) but they have 25-odd AWCs under them so it will probably take a while before they get back to us on including new names in our registers.” On being asked if these instructions were given to her in writing, she said, “Our orders stand that you must not cross the road. But this isn’t given in writing.”

Under a bright street light, with cars zipping past and trains running on the other side of the wall, Rekha and her family sleep against their belongings to protect them from thieves.

After this meeting this writer met Kavita Jadhav, under whose supervision is the AWC in question. On being asked why the homeless children were not being registered at AWCs, Jadhav said, “The children are irregular in their attendance. Also, there are times when the children are dirty. The slum children, who come to the centre, don’t want to associate with these kids and their parents raise objections. We understand the situation. They don’t have facilities like access to water to bathe and fresh clothes to wear. But we can’t do anything about that.” She denied receiving any official instruction to not register homeless children into the scheme.

Ms. Indu Pardesi, the Child Development Project Officer (CDPO), the highest official in charge of the AWCs in the area, said there are no rules that prevented the homeless children from being registered in the centres and that the scheme must include the homeless kids as they are the most malnourished. She, however, did put the ball in the AWWs court, and added, “There is a protocol to follow. The rule says that you need to survey the community first, before giving them any amenities. Accordingly, each worker conducts the survey themselves.”

Meanwhile, Bhalerao has been trying to get homeless children from the two communities registered into AWCs for over a year but hasn’t succeeded. “Each time I visit the AWC, they have a new excuse to not enrol the children. They keep passing the buck. The AWW says it’s the supervisor’s fault, the supervisor says talk to the CDPO; the CDPO says there is no problem but then cites some other problem or blames the AWW,” says Bhalerao.

NGOs working with the homeless in every part of the city are given similar excuses by AWWs and supervisors for not extending the scheme to the homeless. When

Aakar Mumbai, an NGO that works with homeless in Mumbai’s western suburbs, tried to enrol homeless children in ICDS centres in 2011, the excuses that they were given were strikingly similar to what Bhalerao has been hearing. “We tried enrolling homeless children in a centre (ICDS) in Andheri (in Mumbai’s western suburbs) but they resisted. They said they are dirty, they said the rules don’t allow them to enrol homeless children; they also said that they were running to full capacity. After several arguments they asked us to get permissions from their seniors. We surveyed our communities and gave them a list of homeless children with all possible details. We spoon fed them, did everything that they are supposed to do, but they just did not want to help. We continued to request for a year and finally, met an officer who said, ‘It is not within our rights to help you with these issues and directed us to meet the commissioner. Our homeless children are still struggling to avail the benefits of the scheme,” says Vaibhavi Padave, Secretary of Aakar Mumbai.

In Mumbai, development sector professionals claim, the implementation of the ICDS scheme is plagued with corruption, lack of accountability and realistic fund allocation, and resistance of AWWs to impart their duties.

An anganwadi worker in Mumbai gets paid only Rs 4,000 per month and the anganwadi helper, who works under her, gets paid Rs 2,000 per month. The government provides merely Rs 750 a month to rent out space to run the AWC, which in Mumbai, known for its high property prices and rents, is near impossible to find. “One can’t rent a room for that amount anywhere. So the centres run in slum homes. Families rent out their homes to the AWC for two hours each day to make some extra money. These rooms are no bigger than 200 square feet. The belongings of the family living there are strewn all around. They family cooks there, eats there, the television is on at times, family members talk to each other; how can 40 children study in such a space? Also, if the owner of the house says that the homeless children are dirty, they belong to a lower caste or if they are a nuisance and they don’t want them in their house then the AWWs have to listen to them, else they will stop renting out the space,” explains Bhalerao.

When children are taken to an AWC, the AWW has to weigh them, measure their height and note their details in a register. In most cases where the NGOs have attempted to enrol homeless children into the AWC, the workers have not followed this procedure. Once a child is officially registered into the scheme, the AWW has to, as per rule, maintain a record of the child, which includes weight, malnourishment levels, immunisation and so on. In the case of pregnant women, their children have to be registered too. In such a child’s case, the AWW have to maintain a six-year record.

Kreeanne Rabadi, the regional director, west (India), of funding agency

Child Rights and You (CRY), says, “It’s a question of accountability. Once you (a child) officially come on board the AWWs are supposed to maintain registers and they don’t want more work. Also, they’ve not been invested in, in terms of salary and training, so they are not interested and neither is the government.”

One of the biggest problems with the scheme is that most of the centres in the city are functional only on paper. As per government rules, an AWC can run only if it has at least 40 students. The writer, during the course of this research, visited four ICDS centres during working hours and, on all occasions, not more than three children visited the centres. None of the centres had any visible signs of the AWW imparting pre-school education to children; the children who visited ate their meals and left within minutes, and exhaustive interviews with social workers across Mumbai revealed the same. According to the social workers, surveys conducted by CRY and NGOs, most AWCs across the city barely have half the minimum number of children required for the centres to run. “But the teachers, instead of registering homeless children, prefer to fudge records and receive their salaries. The quantity of food the government sends them each day is to serve at least 40 children. Once in a while, a select few AWWs allow four or five homeless children to come and take their daily quota of food and return immediately. The food that they give the homeless children is what they receive for registered slum children, who often don’t turn up,” claims Padave.

“There have been cases where slums have been wiped out after people have been rehabilitated in government homes, but the teacher has continued to maintain fake registers,” she adds.

In Mumbai, the ICDS is the only scheme that the government has to address the situation of malnutrition. However, the scheme isn’t reaching the most vulnerable population. For homeless children, the services the government promises to extend through the ICDS scheme are essential for their development. Just this one scheme, if implemented well can build the immune system of homeless children, prevent malnutrition, give them the ability to cope with the school system and reduce dropout rates.

The government needs to assess the failings and misappropriation of funds and redirect the scheme to children, who need it the most. This needs to be done urgently; else Rekha might end up losing her third daughter Payal, who is five-months-old now. She will try to conceive again for the fourth time and this time as well, there will still be no AWW to advise her to not conceive at such short intervals, she will not be provided nutrition during her pregnancy, nobody will connect her to the primary health centre for regular check-ups and immunisation and she may give birth to a weak baby, who may not survive yet again.

![submenu-img]() Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…

Meet Gautam Adani’s ‘right hand’, used to work as teacher, he’s now Rs 1600000 crore…![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh

Volkswagen Taigun GT Line, Taigun GT Plus launched in India, price starts at Rs 14.08 lakh![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..

Remember Abhishek Sharma? Hrithik Roshan's brother from Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai has become TV star, is married to..![submenu-img]() Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now

Remember Ali Haji? Aamir Khan, Kajol's son in Fanaa, who is now director, writer; here's how charming he looks now![submenu-img]() Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..

Remember Sana Saeed? SRK's daughter in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, here's how she looks after 26 years, she's dating..![submenu-img]() In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding

In pics: Rajinikanth, Kamal Haasan, Mani Ratnam, Suriya attend S Shankar's daughter Aishwarya's star-studded wedding![submenu-img]() In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month

In pics: Sanya Malhotra attends opening of school for neurodivergent individuals to mark World Autism Month![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?

DNA Explainer: What is India's stand amid Iran-Israel conflict?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles

DNA Explainer: Why Iran attacked Israel with hundreds of drones, missiles![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..

Meet actor who worked with Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, entered films because of a bus conductor, is now India's..![submenu-img]() Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...

Meet Bollywood star, who was a tourist guide, married 4 times, went bankrupt, his son died by suicide, then...![submenu-img]() This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..

This actor made Sharmila Tagore forget her lines, once did film for Rs 100, could never be a superstar because..![submenu-img]() Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'

Mumtaz urges to lift ban on Pakistani artistes in Bollywood: ‘Woh log hum logon se...'![submenu-img]() Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...

Not Kiara Advani, but this actress was first choice opposite Shahid Kapoor in Kabir Singh, she rejected because...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Yashasvi Jaiswal, Sandeep Sharma guide Rajasthan Royals to 9-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?

IPL 2024: How can RCB still qualify for playoffs after 1-run loss against KKR?![submenu-img]() CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs LSG, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL

RR vs MI: Yuzvendra Chahal scripts history, becomes first bowler to achieve this massive milestone in IPL![submenu-img]() 'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand

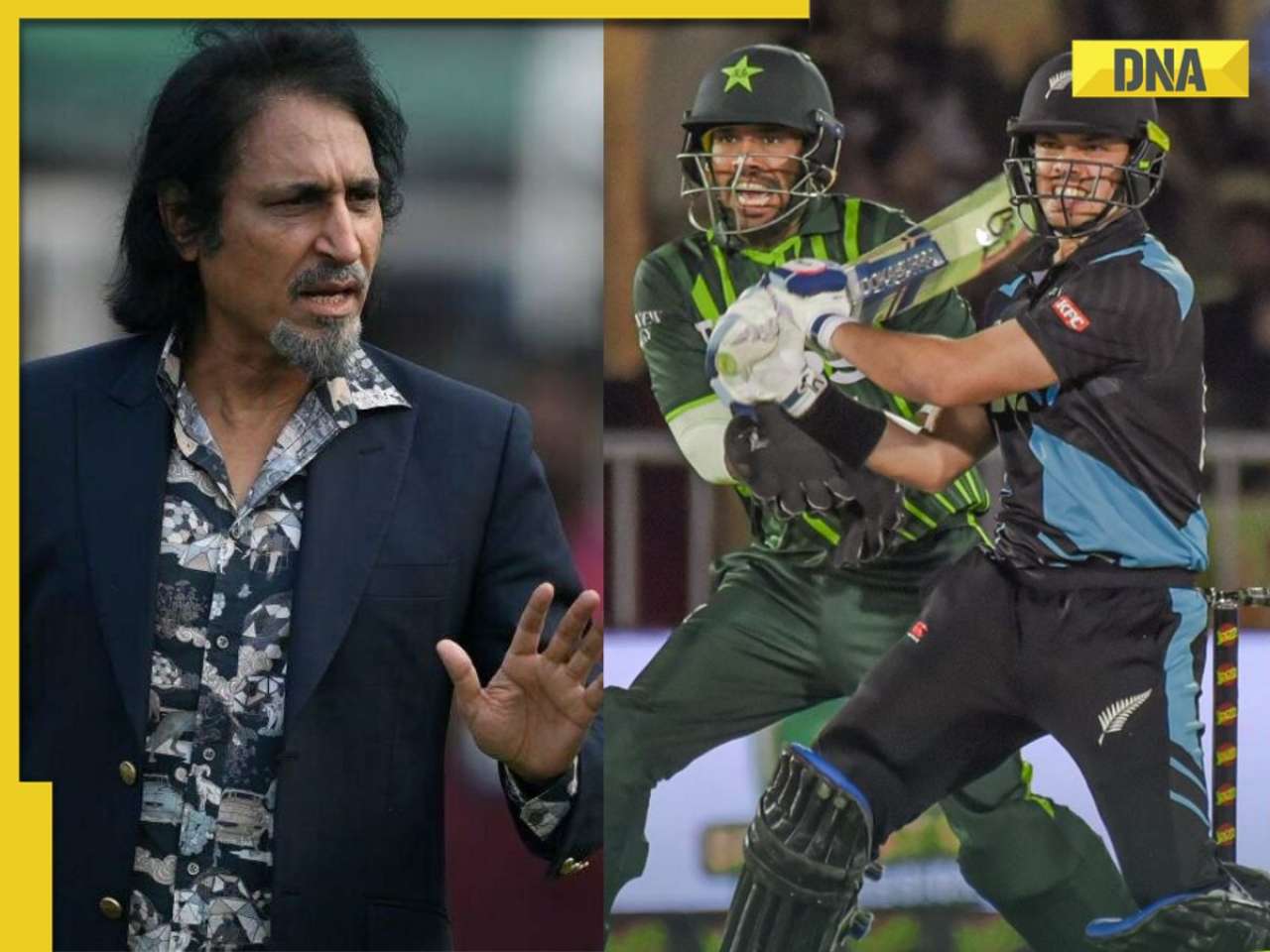

'Yeh toh second tier ki bhi team nhi': Ramiz Raja slams Babar Azam and co. after 3rd T20I loss vs New Zealand![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani likely to get married to Radhika Merchant in July at…![submenu-img]() India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...

India's most expensive wedding costs more than weddings of Isha Ambani, Akash Ambani, total money spent was...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'

Meet Indian genius who lost his father at 12, studied at Cambridge, took Rs 1 salary, he is called 'architect of...'![submenu-img]() Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity

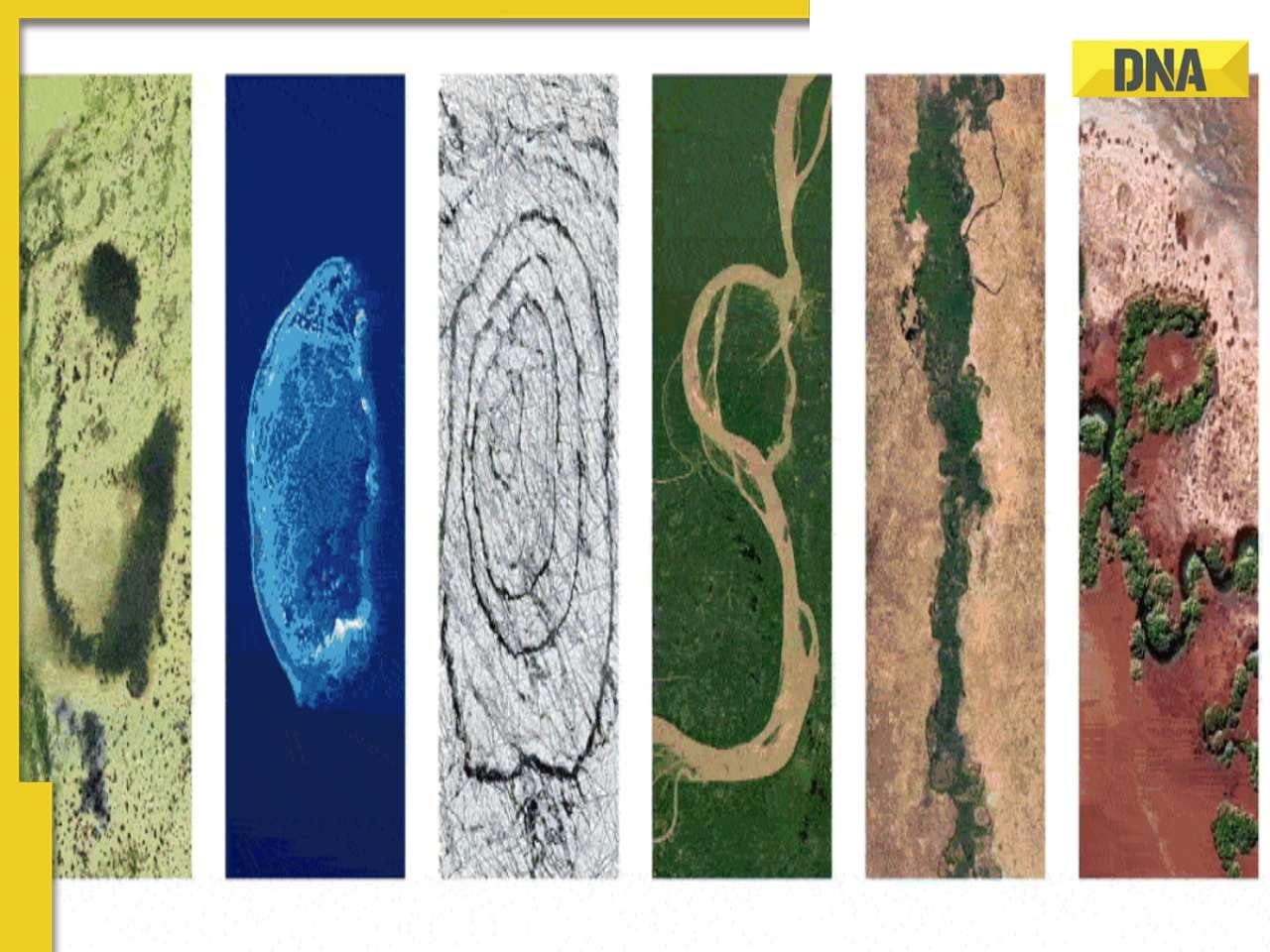

Earth Day 2024: Google Doodle features aerial photos of planet's natural beauty, biodiversity![submenu-img]() Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

Meet India's first billionaire, much richer than Mukesh Ambani, Adani, Ratan Tata, but was called miser due to...

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)