The noise surrounding Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) refuses to die down. After BSP supremo Mayawati blamed EVMs for her party’s poor show in the Uttar Pradesh elections recently, as many as 16 parties have sought the intervention of the President to address apprehensions over the authenticity of EVMs.

Of course, a number of parties and public interest organisations have petitioned the courts to address their concerns. Controversies and lawsuits over EVMs are not unique to India. In fact, ever since it was first introduced in the 1960s in the United States, EVMs have often been controversy’s favourite child, while fathering many a litigation.

In the near past, it was the notorious 2000 Florida voting fiasco that put the spotlight on EVMs. The irregularity of these machines was widely considered a key factor that influenced the final outcome of the Presidential elections. This perception, in turn, led to an investigation of EVMs. Elsewhere in the world particularly in Latin America and Europe, ever since their introduction, these machines have often been reduced to a whipping boy by opposition parties.

While a handful of countries have abandoned EVMs and gone back to their old paper ballots system — particularly a few European countries — a vast majority of countries including its pioneer, USA, continue to back them.

The USA and many other countries have not abandoned them for reasons that are quite simple. They are super efficient, inexpensive, greatly reduce invalid votes, prevent organised rigging and stifle bogus voting.

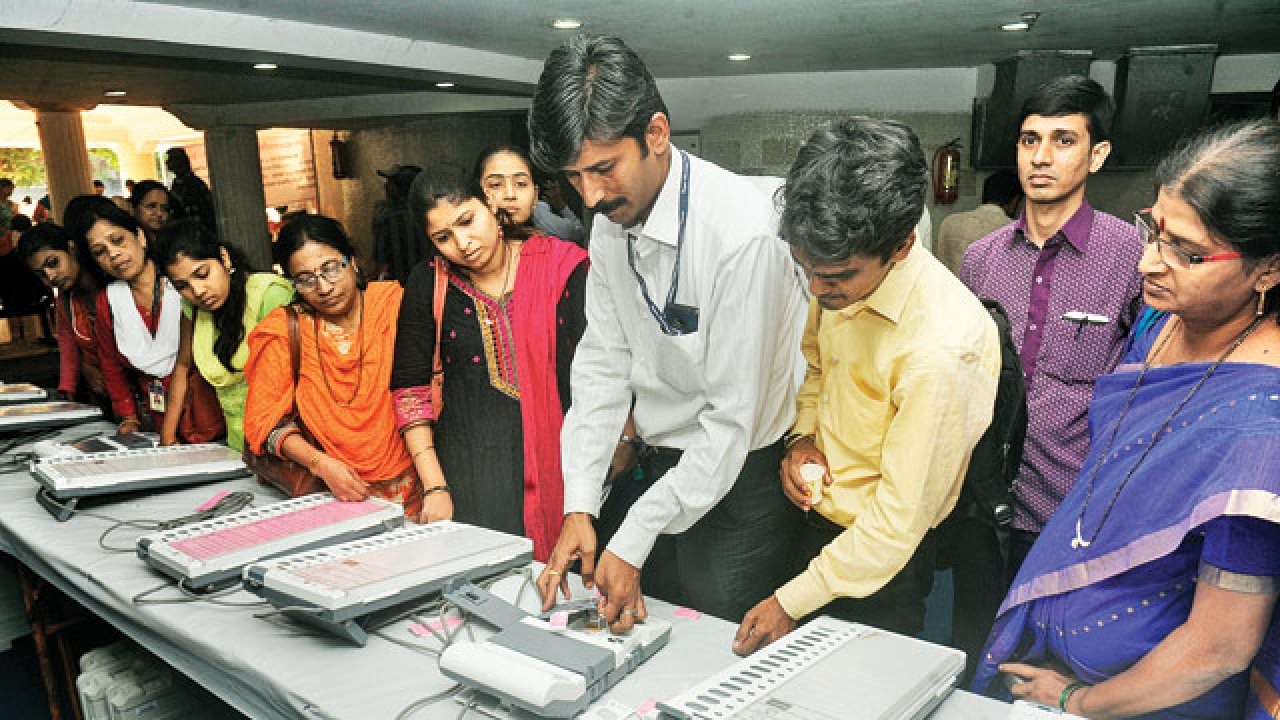

In India’s case, EVMs have been true game changers. As has been extensively documented by academic studies and electoral surveys, EVMs have greatly enhanced transparency and fairness in the electoral process by eliminating booth-capturing and systemic rigging; problems that were endemic to the India of the 70s and the 80s.

EVMs have had a two-fold effect: Firstly, they have deterred criminals and organised mafia from influencing the electoral process while empowering women and marginalised groups to cast their votes without fear.

Secondly, electronic machines have helped cut costs and bring results in a matter of hours and days. A testament to the efficacy of these EVMs is a host of recent studies, which show that the use of EVMs in India has dramatically stoked public faith in India’s electoral democracy.

Naturally, there is no going back on EVMs, unless a much better, proven and inexpensive alternative presents itself. Given the recurrent challenges to conducting a free and fair election in India and the massive size of its electorate, there seems to be no better an option than EVMs for conducting elections.

While these machines have been the recipient of a lot of blame, they have also often been hailed by political parties and courts as tools that have ushered in transparency, accountability, and fairness in the polls, so much so that India’s expertise in this domain has been sought after by many new and emerging democracies across the world.

Naturally, it is in India’s interest to make them reliable, credible and free from suspicion. For that to happen, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has to allow these machines to be publicly audited and verified by independent bodies and experts as is being done in many advanced democracies.

For instance, since 2007 many states in the US have been undertaking a “top-to-bottom review” of these machines.

Similarly, a number of countries have introduced voter-verified paper audit (VVPAT) to ensure a second layer of security to possible hacking or tampering of these machines.

While the commission has taken a positive step by pushing hard for a paper audit trail along with EVMs, this alone will not allay the fear and apprehensions of political parties.

For VVPAT to be useful and effective, ECI will need to conduct extensive verification of voting records and actual results in constituencies on a random basis. These results should then be publicised, once the election results are announced.

To ensure that the process is free of institutional bias or collusion, the paper audit process must have independent experts. This would serve as a double-check on the authenticity of EVMs, dousing a multitude of doubts that Indian political parties have raised against them.

Instead of aggressively campaigning about the invincibility of the EVMs, the ECI is better off in trying to match the unparalleled standards of EVMs set across the globe. It is among the few public institutions in India that enjoy unprecedented public trust. It must do everything to maintain such unwavering public faith.

Niranjan Sahoo is Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.