The paradox of documentary cinema is that it is neither truth nor lie, but both. As the Canadian filmmaker Wolf Koenig says, ‘every cut is a lie, it’s never that way, but you’re telling a lie in order to tell a truth’. The power of documentary therefore, is that it can manufacture a false reality, far more incisive than the realities we experience in our every-day lives. Nisha Pahuja’s 2012 film The World Before Her, which finally made it to Indian multiplexes this month, weaves together two distinct orders of reality to convey a larger point about the pervasiveness of patriarchy in contemporary India.

Given the value of the footage, it is unfortunate that the filmmaker only manages a rudimentary narrative that doesn’t allow ambiguities to breathe. It seems as if Pahuja came to India to make a film on the Miss India contest, but after a chance meeting with the Durga Vahinis later, realised that the more interesting film lay there, and ended up with a hotchpotch of footage, forced together in post-production. Nonetheless, this should not detract from the significance of the film, the remarkable access Pahuja managed to negotiate with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, which runs the Durga Vahini camps, or the fact that it made it to Indian cinema halls during a climate of increasing censorship of debate and expression. As the Argentinian filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino say about their idea of a radical Third cinema, ‘we realised that the important thing was not the film itself, but that which the film provoked’.

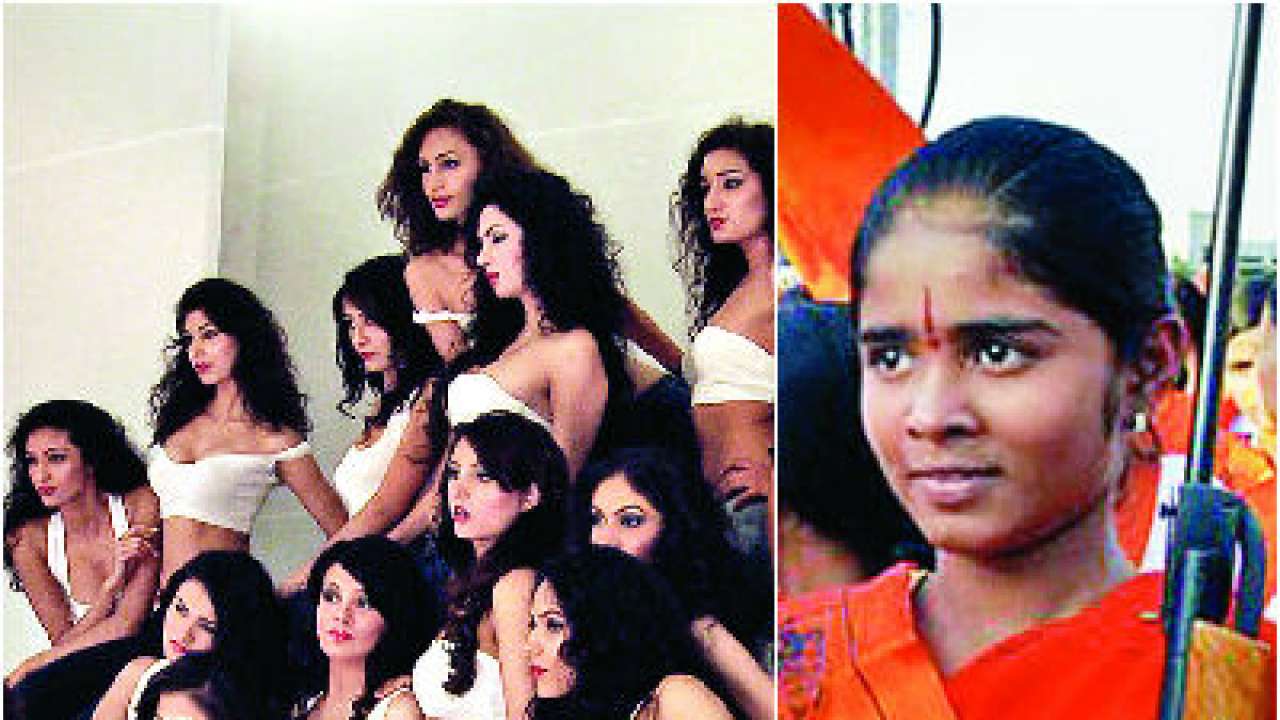

The World Before Her cuts between the lives of young urban middle-class aspirants being trained to compete for the 2011 Femina Miss India crown and girls from rural, predominantly lower caste and working class backgrounds, undergoing training by Hindutva ideologues in a Durga Vahini camp near Aurangabad. Ruhi Jain, a Miss India contestant from Jaipur dreams of making it big in the international world of glamour, and Prachi Trivedi -- an intriguing, feisty woman who admits to her trans-gendered inclinations -- yearns for a successful career as a leader within the Sangh. There are other intermittent characters too, girls belonging to both camps, and their parents. At some point one realises that the independence that Ruhi and Prachi are chasing is ephemeral, and merely feeds into a strongly patriarchal system that believes women’s bodies and minds need disciplining to serve global capitalism and the Hindu nation. The girls seem to know it too, but accept it as part of the trade-off.

What is striking is that both Ruhi and Prachi hang their personal ambitions on the hook of patriotism, couching their desire for success and fame under the garb of ‘symbolising Indianness’, modern or otherwise. The dangerous seduction of nationalism as an ideology is remarkable given that the material realities of national belonging involve tedious production of documentary evidence, public shows of allegiance, and coercion to conformity. A constant, and often violent, manufacturing of consensus is essential for nations to exist and women and technology have been crucial to this enterprise. The aggressive instructions at the Durga Vahini camp commanding young girls to be ‘good Hindu women’, learn the shlokas and martial arts, to hate Muslims and Christians, and ultimately marry a Hindu man to bear him sons, as well as the nipping, botoxing, and stitching into shape of bodies seeking out a unitary idea of global beauty in the Miss India camp, both invoke regimes of terror that harbour little tolerance for dissidence.

The welding together of the critique of the glamour industry and of militant nationalism in Pahuja’s film points a finger at patriarchy, but stops short of critiquing women’s own complicity with the system. The sheer morbidity of women parading silently, torsos covered with a Ku Klux Klan-type white garb, while Marc Robinson leers sleazily to determine whose legs have the most sex currency makes one wonder why the ‘modern Indian woman’ doesn’t have the boobs to stick her heel up modern India’s arse? Or why Prachi Trivedi doesn’t use her martial training to break the arm of a 100 kg man, to return with love her father’s gift of the hot iron rod, a lifelong reminder of the consequences of rebellion? But perhaps the most difficult thing to do is to say ‘I won’t obey’.

Take the absurdity of the scene where Prachi’s mother huddled between her daughter and perennially shirtless husband, watches the Femina Miss India show with apparent curiosity, while the duo harshly condemn the nudity on display and the destruction of ‘Indian culture’. Where are the voices of those silenced by being consistently subjected to hypocritical and crass ideological lashings? Like the elderly Muslim man, whose only recourse is to turn his face and walk away when confronted by a militant demand of conformity with the Hindu nation by the Durga Vahinis during a street procession. But these are voices beyond the pale of the film.

The insidious symbiosis of global capitalism, patriarchy and nationalism has delivered us into the eager arms of a strangler, where freedom of speech, love or thought seems like a distant phantasm. As Prachi points out, bereft of any irony, the very right to life for a girl child is the transactional bond to life-long servitude to the male order. But women, capital, patriarchy and nationalism are old lovers, old comrades, and old enemies so where do we go from here?

The assertion to self-dignity and worth demands tremendous courage, but history gives us hope. And until such time that a new modus operandi is gathered, we should take succour in the words of dreamers and fighters, and like Maya Angelou say, still I rise:

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops.

Weakened by my soulful cries.

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard?

'Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin' in my own back yard

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I'll rise.

(An excerpt from ‘Still I Rise’ by Maya Angelou)

The writer is Associate Professor in Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University