The 1918 influenza pandemic killed an estimated 100 million people globally. The pandemic’s convoluted genesis and its frenetic and catastrophic course make it still a topic of much research. The pandemic struck in three distinct waves between March 1918 and March 1919, the first two waves striking during the endgames of World War I. Unlike most outbreaks, this pandemic felled mostly healthy adults. The pathogen was an unusually aggressive strain of swine flu; it caused devastatingly strong immune reactions which flooded lungs and airways.

Weaker immune systems of children and the elderly resulted in fewer deaths among those groups. The war, massive movement of men and material, malnourishment, overcrowded medical facilities and poor hygiene (which led to secondary infections) aggravated the situation. Modern transportation systems made the disease spread faster and farther. India was struck hard: about 17-20 million died. However, the pandemic did not enter India’s national memory as a terrible but momentous event, unlike other past calamities.

Due to the War, the belligerent governments censored or downplayed the pandemic. Only neutral Spain reported its true impact: the perception that the pandemic began in Spain was thus formed. The popular term for the pandemic is still “Spanish Flu”. Many nations have nicknames — laced with spite, black humour or ignorance — for the pandemic. The first confirmed outbreak was in Kansas, US, in March 1918. The first wave lasted till June but global death rates were not very high. An American base in France however became a major disease vector. This base saw millions transit every week. It had an overcrowded hospital and was ringed by piggeries and farms.

These conditions allowed a highly lethal virus strain to develop. The resultant second wave (August-November) was catastrophic. The Flu raced across the globe, from the Arctic to Polynesia, killing millions of hosts shortly after infection. It scythed down commoners, celebrities, soldiers, generals, leaders and royalty. A third wave struck in February 1919, but rapidly abated. The virus killed its hosts too fast, before more people could be infected. Also, the virus mutated into a non-lethal strain — perhaps mere chance saved humanity.

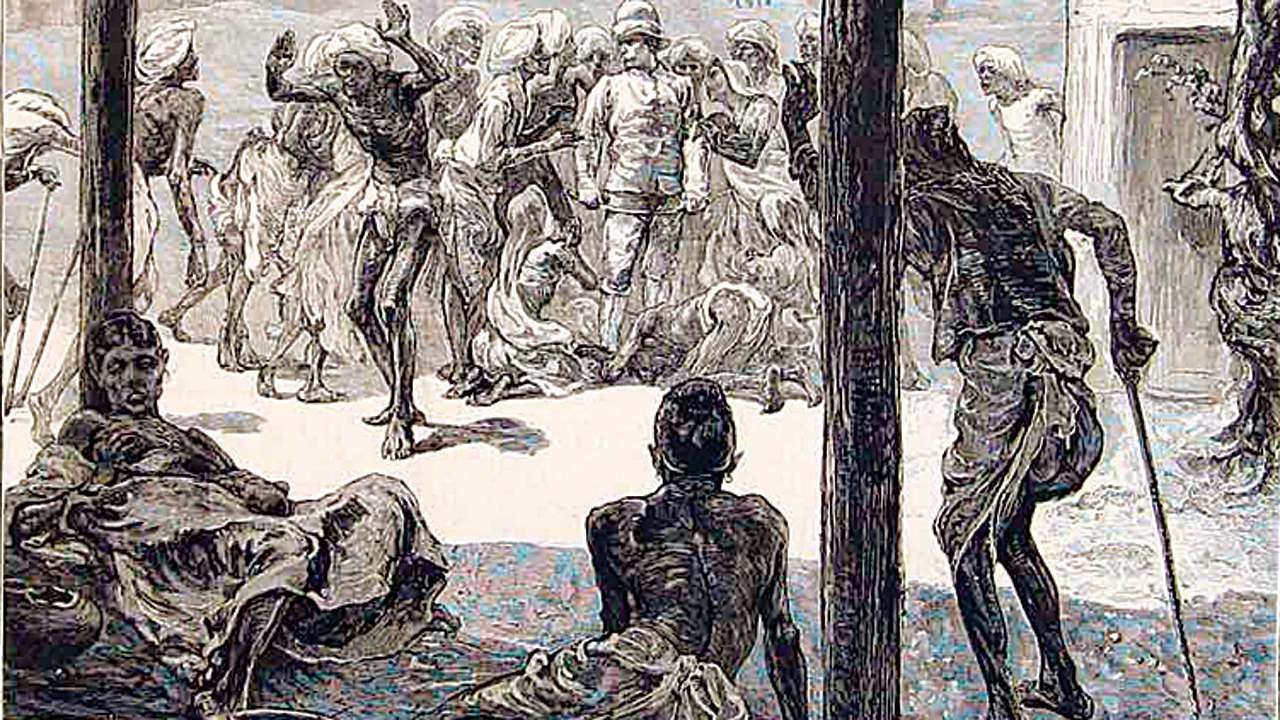

The second wave struck India hard in September 1918, through soldiers returning from the War. Western, Central and Northern India were hard hit, but the East and South were much less affected. Certain regions showed mortality as high as 102.6 per thousand. This pandemic was more destructive than past Indian famines, and killed twice as many as the recent great plague (1896-1907). However, the Flu pandemic did not elicit the level of reactions that previous calamities did. Events such as the Great Bengal Famine, the Skull Famine, the Chalisa Famine, etc. had enduring impact on our national memory. The great plague, which originated in China and spread alarmingly in India, also influenced Indian society and the freedom struggle. Fears of the plague growing uncontrollably in India and causing another Black Death in Europe led to Western threats of sanctions. In response, the British launched harsh anti-plague campaigns, totally disregarding socio-religious sensitivities.

Millions fled the cities fearing both plague and plague containment. Myths of Western medical conspiracies also strengthened. For example, many believed that Indians were secretly dismembered and processed in hospitals to extract a medicinal fluid called “Momiai”, which was used to protect the British from the plague. Violent agitations, and the assassination of the plague commissioner resulted in severe reprisals.

Press censorship was in effect when the 1918 pandemic struck. Institutional memories of the plague were also fresh. The British therefore downplayed the Flu, and made limited but focused efforts to fight it. They had also recently overhauled the public health apparatus to accommodate Indian sensitivities. Some Indian organisations also rose to meet the pandemic’s challenge. Therefore, the efforts to fight the Flu did not evoke widespread anger.

Moreover, 1918 was a major juncture in the freedom struggle. Gandhiji was becoming the paramount leader of the recently reunified Congress. The Indian National Movement was forging socio-political alliances, adopting mass agitations, and planning responses to the menacing Rowlatt Mission. These developments captured the imagination of the (mostly) urban, politically conscious populace, and diverted attention from the pandemic – of which there was limited and confusing information. The Flu coincided with the unprecedented slaughter of the War. This factor, and the pandemic’s utter speed made it difficult for society to truly process the calamity. Finally, great mass-deaths due to famines and epidemics had occurred across India in the not-so-distant past: this lessened the pandemic’s true significance for the people, especially rural Indians.

The 1918 pandemic perhaps deserved to be marked as a momentous event in national memory: stark memories of such calamities have transformed many societies and governments for the better. However, this pandemic, which killed more Indians than any other event, is largely forgotten outside the realms of academics and research.

The author, an IIM Ahmedabad graduate working in the energy sector, has a keen interest in history, politics, and strategic affairs