One of the interesting sideshows of the 2014 general elections was the repeated invocation of the ‘Idea of India’ by almost anyone who had something to say about anything. First it was the political parties from the Congress to the Left, followed by responses from BJP and their friends. Then it was the turn of various public intellectuals who added their share to the confusion, the latest being Gopalkrishna Gandhi who invoked this idea in his open letter to Modi. An outsider could well have been forgiven for thinking that the most important fight in this election was on the ‘Idea of India’.

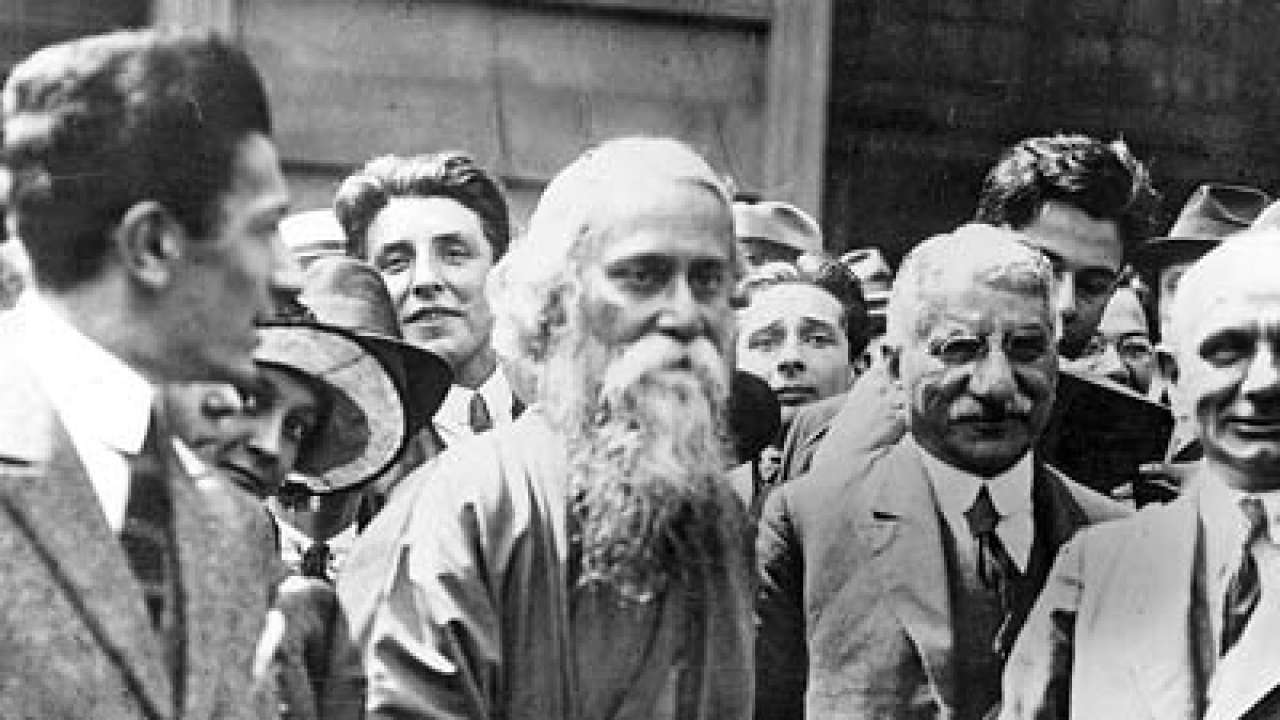

The first question that we have to ask is ‘idea of India’ as what? Idea of India as a nation or as a civilisation? Gandhi, Tagore and Kosambi, among others, spoke repeatedly of the idea of India as a civilisation. Here, I want to suggest a more basic understanding of the idea of civilisation.

The idea of a civilisation is broader than that of a nation. A civilisation by its very character is something which is a path for the future, how a society can be. It is a capacity to integrate the past and future into the present, so that not only is there a notion of historical tradition that influences it but also a notion of a desired future that is essential to it. But both these visions of the past and the future have to be embodied in the present.

So how are we doing on these counts? Is this debate on the idea of India really about the idea of India as a civilisation?

Consider how we engage with the past. We are still engaging with the past as if our idea of India is of a nation and not of a civilisation. We do not know how to disagree, we do not study texts seriously, we do not teach old languages in our colleges and universities. In the public domain, the past is repeatedly mythologised and does not become a material for the present.

The mythologisation of history means that we, as a public, can make claims about history without taking the effort to consider a long textual tradition. We have gone past a state of being ashamed when we are confronted with the lack of interest in studying ancient and medieval texts in India.

If you look at the amount of scholarship on ancient and medieval Indian mathematical and philosophical texts by the Japanese, Chinese, French and Germans (other than the more well-known Anglo-American researchers) it makes you ask: to whom does a history of India belong? And when scholars write problematic books about these texts, we have aggressive reactions and not scholarly ones. We, as Indians, can claim ownership over these texts, tradition and our history only by being part of a meaningful debate on claims and counter-claims. We have no claims of ownership to these texts just because we are born in India and live here. Or, if some might want to claim that they indeed have an ownership for this reason, then it is incumbent on them to state the reasons for believing so.

If we do not encounter our history properly, then we are doomed to only reacting to the idea of India as a nation. The very idea of history is itself civilisational and cannot be reduced to utilitarian ends. Reducing it to such ends only makes history of the past an ideology of the present — obviously so since utilitarian ends can only matter to us in the present moment. So the real challenge about engaging with our history is to understand it without wanting to see what uses you can make of it now.

What then of the vision of the future which is an integral part of a vision of India as a civilisation? Given that each one of us in India (and now increasingly loud voices of those outside India who insist on having a say on what the future vision of India should be) might have a different vision of what India should be, how is it possible to have some unified idea of a future?

This difficulty is actually the most important one in understanding what it means to be a civilisation. If each of us desires an India that is influenced by personal beliefs, prejudices and petty desires, then of course it is going to be impossible to reconcile all these views. However, if we think civilisationally — if we think with principles that may be universally or at least ‘socially’ common — then we would have a way towards forming a civilisational idea about India.

And what could those civilisational principles be? Anand Teltumbde wrote a powerful article in a newspaper a few days ago about the response of the country to the brutal rape and murder of two Dalit girls in UP. The general apathy and the lack of any serious response to this heinous act only point to a civilisational absence in the country. When a vision of India by an individual is not based on empathy for all those who are different from him or her, then it is not a civilisational vision but only a crassly utilitarian one.

We are a country — and I say this with sadness — that does not show civilisational impulses. Increasingly, the dispossessed and the poor are becoming imaginary specks in the horizon. They are absent everywhere; earlier there were at least writers and film-makers who told the stories of these people. Today, even that has become increasingly difficult and irrelevant. To add to this insult, more difficulties are being heaped on the marginalised and the dispossessed. There is no meaningful public health available today. We are becoming one of the world’s largest consumers of a basic commodity like private water.

To be civilised is quite simple: it is to know how to respect those who are less fortunate than you and those who disagree with you — this is a lesson that seems to have become completely irrelevant today.

The author is director of the Manipal Centre for Philosophy and Humanities, Manipal University