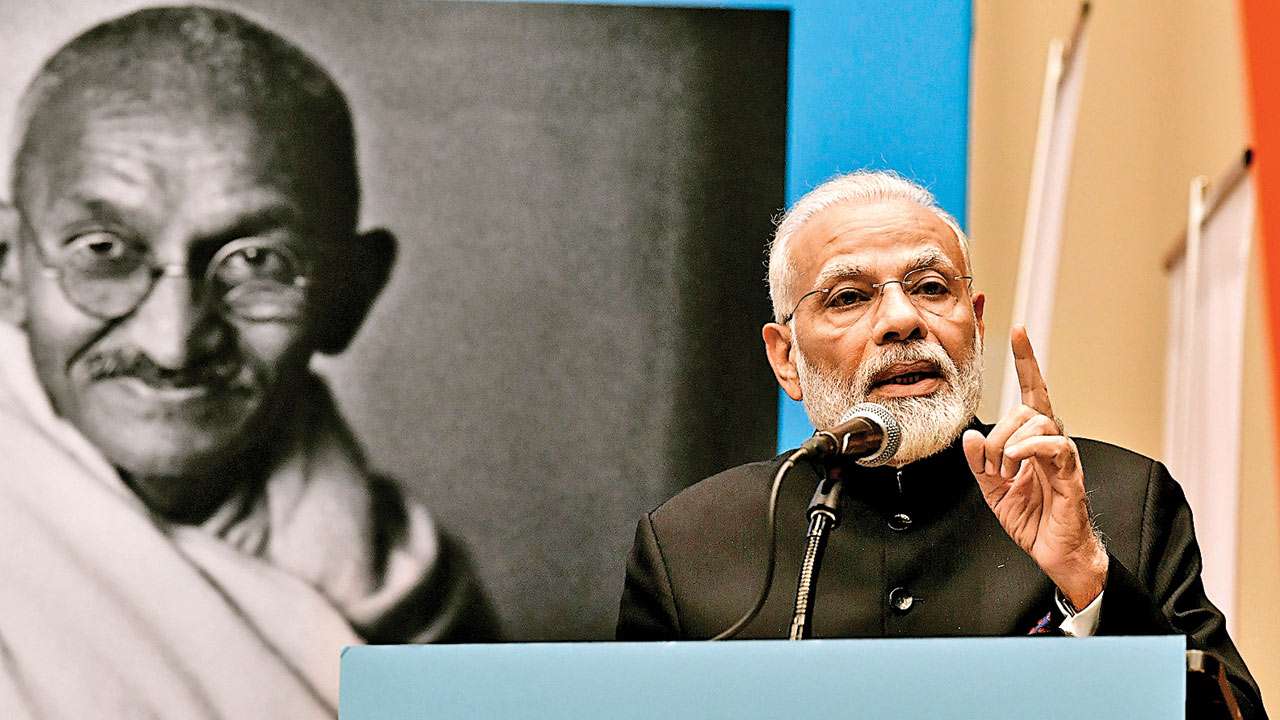

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares to speak at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) on September 27, the focus has swung back on the BJP’s core philosophy: nationalism. How valid is it today?

Mahatma Gandhi was a nationalist. So were Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Why then has nationalism acquired such odium in recent years? The short answer: the meaning of nationalism has been subverted.

This subversion leads even “public intellectuals” — a term that has fallen into some disrepute — like Pratap Bhanu Mehta and Ramachandra Guha to miss the finer nuances of nationalism.

Why do Indian Opposition leaders, historians and academics misinterpret the true meaning of nationalism? A part of the reason is ideological. They despise Prime Minister Narendra Modi and imbue him with their false interpretation of nationalism. They constantly seek a problem for every solution, not a solution for every problem. Their prognostications for India are invariably grim. The references to Kashmir in the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), and the UNGA, is played up by this cabal of India denigrators. The references these international bodies make are merely proforma. They carry no weight. The denigrators know this, but wilfully subvert the narrative.

The government deserves criticism across a host of issues. But such criticism — which should spare nobody, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi — loses credibility if it is built on prejudice. India doesn’t suffer from too much nationalism. It suffers from too little.

At a recent event, sociologist Ashish Nandy told the audience: “I’ve worked on nationalism, so I am telling you with some confidence. You read all the nationalist texts and you tell me if this nationalism is different from our nationalism, or that nationalism is distinct from other kinds of nationalism. You cannot find it, all nationalisms are the same, the texts are the same, only the names, only the minor, trivial details differ. There is no difference between nationalism anywhere. Psychologically speaking they are absolutely the same profile.”

Thus, in Nandy’s view, Mahatma Gandhi’s nationalism in the 1930s was the same as Adolf Hitler’s nationalism in the 1930s. Read the key part of Nandy’s comment again: “All nationalisms are the same. There is no difference between nationalism anywhere.”

But, of course there is a difference — in both historical and contemporary terms. This is how, as I wrote elsewhere, the finer nuances of nationalism need to be understood: “One reason why the Congress and the Left have a poor understanding of nationalism is that they use European reference points. It is fashionable in the West and among India’s nouveau elite to say that patriots spread ‘love’ and nationalists spread ‘hate’. But that is a Western post-colonial construct based on European nationalism that led to World War II. Indian nationalism is very different.

“German nationalism in the 1930s, for example, sought to invade and conquer. Indian nationalism under Mahatma Gandhi, in sharp contrast, was non-violent and sought to free India from British colonial occupation which, like German ‘nationalism’, was invasive, violent and expansionary. German and British nationalism were not nationalism at all but jingoism. Employing a deliberate sleight of hand, the Left attempts to discredit Indian nationalism today by conflating it with European ‘nationalism’.

“In India, ideologues on the Right, too, make a fatal error: they conflate nationalism with Hindu nationalism. It is not. In its truest form, nationalism is inclusive. To protect national interest means protecting every Indian’s national interest: Hindu, Muslim, Christian or Parsi, rich or poor, Brahmin or Dalit, Sunni or Shia, male, female or transgender. Nationalism seeks national advancement, but not at the cost of other nations, races or creeds. Real nationalism is fair, open and embraces diversity. It seeks to guard India from terror, promote the country’s economic interests by globalising the Indian economy and protect the rights of minorities by empowering them.”

Meanwhile, patriotism, we are told, is the antithesis of nationalism. In short, patriotism is selfless and good. Nationalism is selfish and bad. This is how Nandy frames it: “Old-fashioned patriotism was good enough for even Europe at one time, and in India today, it is by blurring old-style patriotism and love for the country — which is natural and biological — that we have tried to strengthen nationalism. Nationalism by itself does not make that much sense as old-fashioned patriotism. Every Indian, I should say, is patriotic by nature. You don’t have to teach them to be patriotic, but nationalism is an ideology. Nationalism is not only defined by the love of the country territorially where you were born, nationalism is defined by specific enemies and specific allies. Nationalism is built on that; patriotism doesn’t have that kind of responsibility, it doesn’t define your enemies or friends.”

To Nandy, therefore, “nationalism is defined by specific enemies” while “patriotism doesn’t define enemies or friends.”

He makes the same classical mistake others of his ilk do, conflating nationalism with aggressive intent.

Gandhiji, a consummate nationalist throughout his life, used ahimsa, non-violence, as his central credo. The enemy was specific — the British — but he advocated non-violent means to confront and defeat it. He was a patriot and a nationalist and showed how they were two sides of the same coin.

Left-leaning historians and academics strive to drive an artificial wedge between nationalism and patriotism. There isn’t one.

The author is an editor and publisher