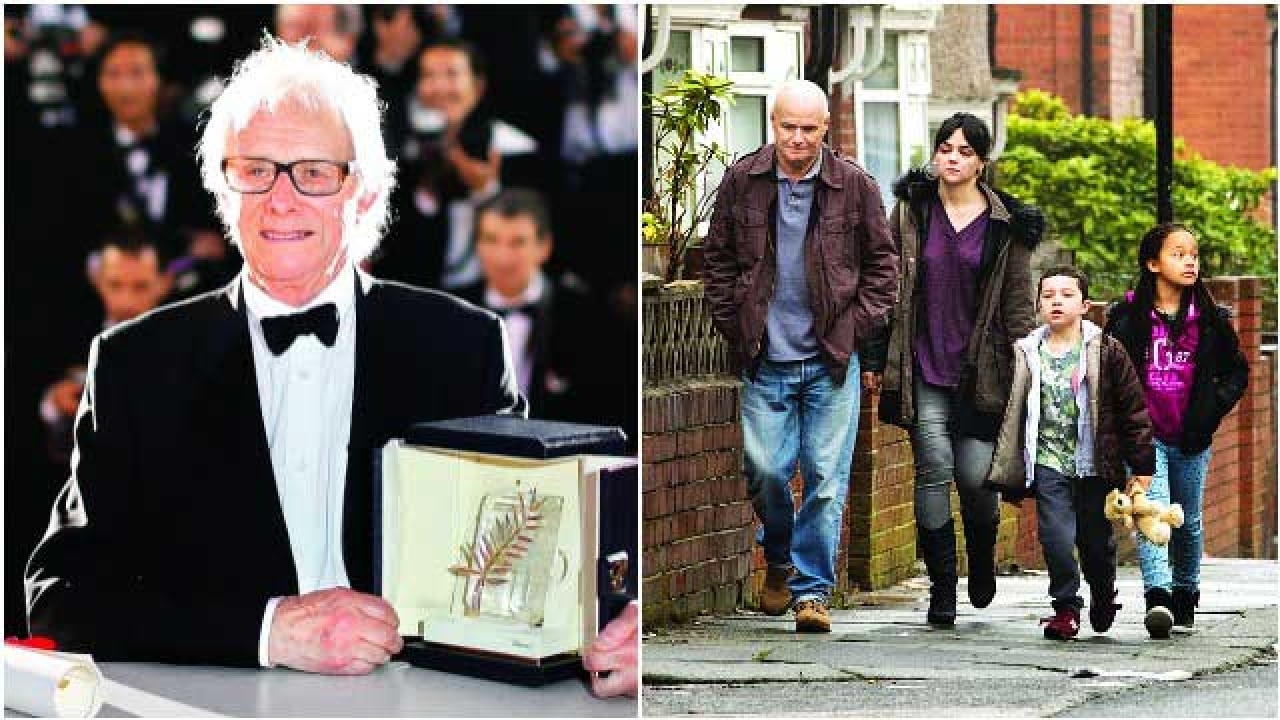

The Palme d’Or for Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake was greeted with more than a few gasps of disbelief last Sunday. Not that the minimalist British film wasn’t universally applauded, but there were at least three other contenders in the 69th Cannes Film Festival — Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann, Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson and Cristian Mungiu’s Bacalaureat — that seemed to have whipped up a bigger buzz in the run-up to the closing ceremony. In picking I, Daniel Blake for the festival’s top prize, the jury headed by filmmaker George Miller clearly opted to go beyond just cinema. It made a statement by embracing the alternative vision of 79-year-old Loach and his long-time screenwriter Paul Laverty.

The film tells the story of a Newcastle carpenter (played by stand-up comedian Dave Johns in a way that is the very antithesis of ‘acting’) who runs into an unfeeling welfare bureaucracy as he navigates the British benefits system after being rendered unfit for work by a heart attack.

In his acceptance speech, Loach put the purpose of his film in perspective. “The world we live in is at a precarious point… We are in the grip of a dangerous project of austerity driven by neo-liberal ideas… that have brought us to near-catastrophe.”

“When there is despair, forces from the far right take advantage. We must give a message of hope, we must say that another world is possible,” the 79-year-old director said, his hand wrapped around his second Palme d’Or.

He was of course referring in particular to his own country, but at the post-screening press conference he asserted that this problem was a pan-European phenomenon. “It is shocking because it is an issue not only in the UK but also all across Europe,” he said.

But more than politics, there is humanity in I, Daniel Blake. And Loach’s second Palme d’Or is a recognition of voices that are usually drowned out in the din generated by vocal votaries of welfare cuts.

As a film, I, Daniel Blake is remarkable for its sustained cinematic simplicity. “The story was strong,” Loach told the media. “We had to be clear, understated, unadorned and sans extraneous movements so as not to deflect attention from the lives before us on the screen.” I, Daniel Blake emerged from hundreds of interviews and extensive research into the plight of those on welfare and attending food banks across the UK. In Laverty’s words, the film was triggered by the need to call out “the sustained and systematic campaign against anyone on welfare spearheaded by the right-wing press, backed by a whole wedge of poisonous TV programmes”.

Who else but Loach could have done it with such force? No contemporary filmmaker is as much a part of the Cannes Film Festival scene as Loach. The director celebrated for his naturalistic, social realist cinema has been a Croisette regular since he was here with Kes in 1970.

Loach won his first Palme d’Or in 2006 for The Wind that Shakes the Barley, a fictional drama set in the years of the Irish war of independence. In I, Daniel Blake, his 19th film to make the trip to the world’s premier film festival and his 13th in competition, he is as sharp and as profoundly humanist as ever.

I, Daniel Blake presents a caustic but dignified portrait of perfectly decent and honest people ground to dust by the State. Says Laverty: “As Ken and I travelled the country, one contact leading to another, we heard many stories. Food banks became a rich source of information… Breaking the stereotypes, we heard that many of those attending food banks were not unemployed but the working poor who couldn’t make ends meet. Zero hour contracts caused havoc to many…”

No wonder I, Daniel Blake is an angry film. But it does not rail and rant against its target — an unthinking system that paints citizens into a corner and then does everything in its power to keep them there.

After a near-fall from a scaffolding, 59-year-old Daniel Blake is reduced to running from pillar to post to secure the State support he needs to make ends meet. His path crosses that of Katie Morgan (Hayley Squires), a young and hard-up single mother of two who relocates to a council flat in Newcastle. That is the only way she can escape the drudgery of life in a homeless hostel in London. But things only turn worse for her. Daniel and Katie fight parallel battles as the former develops a bonding with the latter’s mature-beyond-her-years daughter Daisy and her hyperactive son Dylan, a boy who can never sit still.

Grappling with penury and hunger, Katie takes recourse to desperate measures that undermine her dignity and pride — a fallout that is filled with poignancy. I, Daniel Blake has immense emotional strength, but its ability to move and engage the audience stems from the unwavering control that Loach brings to bear upon the uncluttered narrative. It is a film that breaks your heart but, like all great art, also opens your eyes. “There is inherent cruelty in the way that we run our lives,” says Loach. “In this world, the most vulnerable people are told that their poverty is their own fault and that they must suffer the consequences.”

He adds: “We need a Europe-wide movement to rescue people like Daniel and Katie. If you keep people poor and cornered, exploitation becomes easier.” Loach could be speaking of the world as a whole. Dan and Katie’s modest dwellings, the office of the department of work and pensions, and the food bank — these are the principal spaces in which I, Daniel Blake unfolds. “The film might look improvised, but it was precisely charted,” says the director. “The people working in the food bank are actual employees, as are the people in the benefits office. We tried to create an illusion of reality.” Acknowledging what his cast brings to the table, he says: “It is easy to work with actors because they are full of imagination and vulnerabilities.”

Loach presents the plight of the victims of the British welfare system with such directness and tenderness that it is difficult not to feel intense abhorrence for the way people are turned into mere insurance numbers. And that is why I, Daniel Blake is more than just a film.

The author is a seasoned film critic