His first novel, Kanthapura, written in 1937 when he was only 21 years old, has continued to be acclaimed as a precursor of a kahani - Puranic style of Indic-English.

His preface to Kanthapura is often cited as the quintessential statement or manifesto of Indian writers in English, where he wrote that “English is not really an alien” to India, but like Persian and Sanskrit before, has become the language of governance and of India’s “intellectual make-up.” He continued, “We cannot write like the English. We should not. We can write only as Indians” because the “tempo of Indian life must be infused into our English expression. . . . We, in India, think quickly, and when we move we move quickly.”

His 1937 preface concludes, “There must be something in the sun of India that makes us rush and tumble and run on. . . . Episode follows episode, and when our thoughts stop our breath stops, and we move on to another thought. This was and still is the ordinary style of our storytelling.”

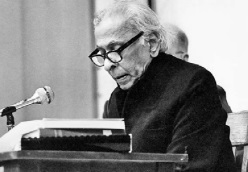

These words written by Raja Rao almost 80 years ago, sound very much like words he spoke to me less than 20 years ago when he described India. His concept was that the idea of India was greater than the terrestrial entity, transcending the material world, offering a gift of knowledge to the planet. Many times in eloquent language he explained his perspective that India's energy or aura, goes out into space, follows trajectories, mutates, vibrates and hums in all directions, thereby influencing the cosmos.

Raja Rao thought there was something in the bedrock of the Subcontinent that hums the Dharma, a glow, an energy that keeps the world keeping on. It's the Dharma's Shakti, the Cosmic hum rising from that inverted triangular piece of land located between Sindh and Bengal, from the Himalayas to Sri Lanka. Raja Rao said that when he was younger, he felt, and saw, and heard India’s metaphysical terrestrial energy as he was approaching India by boat in 1939 fleeing the war in Europe after having lived in France. Raja Rao often spoke about the power emanating from India, the collective cosmic Shakti power that was ‘Indianness’ (Dharma).

He knew scientifically that, he was not off-base theoretically, since India has the oldest rocks on earth from the Precambrian age. In fact, the Narmada flows through the ancient Gondwana Plate. Raja Rao felt that India was an idea that transcended geographical limitations. In his novel The Serpent and the Rope (1960) he wrote, “Anybody can have the geographic—even the political—India; it matters little. . . . India is not a country like France is, or like England; India is an idea, a metaphysic.”

Raja Rao was a sage, for him words were made from light that formed during meditation. He was a sage who practiced Advaita Vedanta and his fictional characters were expressions of that tradition. It can be said this is writings were not real, but were true. One logical political reason that his work was waylaid and forgotten compared to other Indian authors such as his contemporaries Mulk Raj Anand and RK Narayan, is that in post independence India, Socialism was elevated and Raja Rao was critical of Marxism. In Comrade Kirillov, Raja Rao critiqued Marxism and its incompatibility with Indic thought.

His wife Susan Raja-Rao wrote to me concerning his views on communism, “He did not like Nehru’s socialism or Nehru’s whole view on India. He felt it was a misfortune that Nehru had not followed Gandhi.”

Additionally, his works, though patriotic and nationalistic, were spiritual expressions of the absolute... metaphysical writings that only those who are open to the oneness and the totality of that oneness could grasp. But those not able to conceive that concept can't fully appreciate its undulations moving through the work of Raja Rao. Non-duality is the foundational essence found in Raja Rao's work.

He was a metaphysician and mere secular critics can only reference his unique use of English not his transcendent point of view.

Raja Rao was not an easy writer. He demanded attention and honesty. Reading Raja Rao was often more than a mere act of reading. Just as writing was a form of Sadhana for Raja Rao, reading his work was often a form of meditation as well. An honest response to the words of Raja Rao was often threatening to one's carefully cherished illusions and ego, hence, more convenient to ignore, in a new generation, with new literary fashions.

Raja Rao loved the young Americans who filled his classes by the thousands in the sixties and early seventies, the hippy generation. He publically disagreed with Indira Gandhi about the youth who were going to India in droves to find spirituality, many of whom he sent there after having taken his courses.

Rao felt that the time is coming for Hinduism, that India’s spirituality was on the rise internationally. He knew that the time is now, for the Dharma to become more familiar and respected in the West and also better understood in modern India. Raja Rao knew this change was imminent…. A movement he helped to usher in.

Excerpt from Raja Rao’s acceptance for Neustadt Prize in June 1988:

"I am a man of silence. And words emerge from that silence with light, of light, and light is sacred. One wonders that there is the word at all ‐Sabda-‐and one asks oneself, where did it come from? How does it arise?

I have asked this question for many, many years. I've asked it of linguists, I've asked it of poets, I've asked it of scholars. The word seems to come first as an impulsion from the nowhere, and then as a prehension, and it becomes less and less esoteric - - till it begins to be concrete. And the concrete becoming ever more earthy, and the earthy communicated, as the common word, alas, seems to possess least of that original light. The writer or the poet is he who seeks back the common word to its origin of silence that the manifested word become light. […]

One of the ideas that has involved me deeply these many years is: where does the word dissolve and become meaning? Meaning itself, of course, is beyond the sound of the word, which comes to one only as an image in the brain, but that which sees the image in the brain (says our great sage Sri Shankara) nobody has ever seen. Thus the word coming of light is seen eventually by light. That is, every word-image is seen by light, and that is its meaning.

Therefore the effort of the writer, if he's sincere, is to forget himself in the process and go back to the light from which words come. Go back where? Those who read or those who hear must reach back to their own light . And that light I think is prayer."

The author is a writer and Indic Scholar