The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently raised the repo rate by 25 basis points to 6.25 per cent. One basis point is one hundredth of a percentage. Repo rate is the interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks and acts as a sort of a benchmark to the interest rates that the banks pay for their deposits and in turn charge on their loans. The interesting thing is that this is the first time since early 2014 that the repo rate has been raised by the monetary policy committee of the RBI.

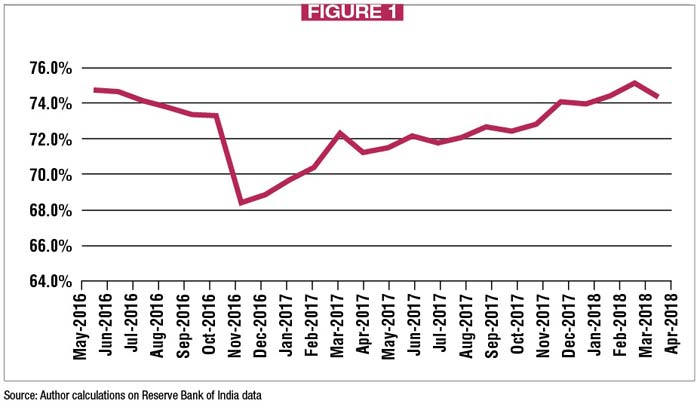

In fact, the banks had already seen this coming, and had increased both their loan as well as deposit interest rates. The question is why? The answer lies in the graph, which basically plots the credit deposit ratio of banks over the last two years.

Credit deposit ratio is essentially the total loans (ie, credit) given by banks divided by the total deposits (both time and demand deposits) that a bank has, at a certain point of time. When it comes to total loans, we consider non-food credit here.

Banks in India give working capital loans to Food Corporation of India and other state procurement agencies to primarily buy rice and wheat directly from farmers. Once these loans are subtracted from total loans given by banks, what remains is non-food credit.

The graph tells us that in March 2018, the credit deposit ratio crossed 75 per cent for the first time in more than two years. The last time this had happened was in March 2016 (not represented in the graph), more than two years back. In April 2018, the credit deposit ratio was at 74.4 per cent.

What does this tell us? Banks cannot lend out all the deposits that they have. Four per cent of deposits need to be held with the Reserve Bank of India as a cash reserve ratio (CRR). And, 19.5 per cent of the deposits need to be compulsorily invested in government securities to fulfil the requirements of the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR).

This means 23.5 per cent of deposits (4 per cent as CRR and 19.5 per cent as SLR) cannot be given out as conventional loans. This leaves 76.5 per cent of deposits, which can be given out as conventional loans. At a credit deposit ratio of 74-75 per cent since December 2017, banks were already cutting it fine. Hence, they started raising interest rates on both loans and deposits, even before the RBI raised the repo rate.

In fact, the interest rates would have gone up almost a year back, if demonetisation had not happened and a flood of deposits had not hit the banks. The huge amount of deposits that were made basically pushed the credit deposit ratio to as low as 68.4 per cent in November 2016.

The general belief over the years has been that at lower interest rates people borrow money and at higher interest rates they are discouraged from borrowing. This is why whenever interest rates are raised, businessmen always start complaining. Nevertheless, the question is does this always hold true?

Let’s consider the four-year period between March 2014 and now, April 2018, when the RBI did not increase the repo rate. The overall lending by banks (ie, non-food credit) during the period increased by 43.6 per cent. Now, let’s take a look at the period between March 2010 end and March 2014 end, the four-year period prior to that. The repo rate during the period went up from 5 per cent to 8 per cent. Interest rates on loans and deposits also moved up accordingly. Nevertheless, the lending increased by 84.5 per cent during the period.

Even when we look at lending in absolute terms, Rs 26,99,350 crore was lent between March 2010 and March 2014. Between March 2014 and April 2018, a total of Rs 25,69,941 crore was lent. Even in absolute terms, lesser amount of money was lent in the last four years than in the four years before that. This, despite the fact that interest rates in the last four years were lower than in the four years prior to that.

What this tells us is that the conventional logic does not always hold true. The point being that the link between a lower interest rate and higher lending is not very strong, as is conventionally thought. Lending happens when the banks are in the mood to lend. In the last four years, banks have not been in the mood to lend, especially to industry. Nearly three-fourths of the bad loans accumulated by banks has been on account of loans defaults made by companies operating in the industrial sector. Bad loans are essentially loans which haven’t been repaid for 90 days or more.

Lending also happens, when borrowers are confident that they will be able to repay the loan that they are taking on. In the last few years that confidence has gone down and hare-brained schemes like demonetisation have only made the situation worst.

Further, in the Indian situation, higher interest rates work well for savers, given that fixed deposits remain the most popular form of saving. This is something that most economists do not seem to take into account while analysing things.

Higher interest rates also work well for the retired individuals, who generate their monthly income by investing in fixed deposits. And a higher rate of interest means a slightly higher income. This is very important in the Indian context, simply because our social security system is very weak.

All in all, higher interest rates are not necessarily a bad thing.

The writer is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. Views are personal.