Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to promote a “Make in India” policy. But the diamond trade probably believes in “un-make in India”. It has sought to corrode the very roots of the diamond cutting and polishing (CP) industry in India. It has destroyed employment potential as well, by misleading (if not conniving with) India’s policymakers. (Read more)

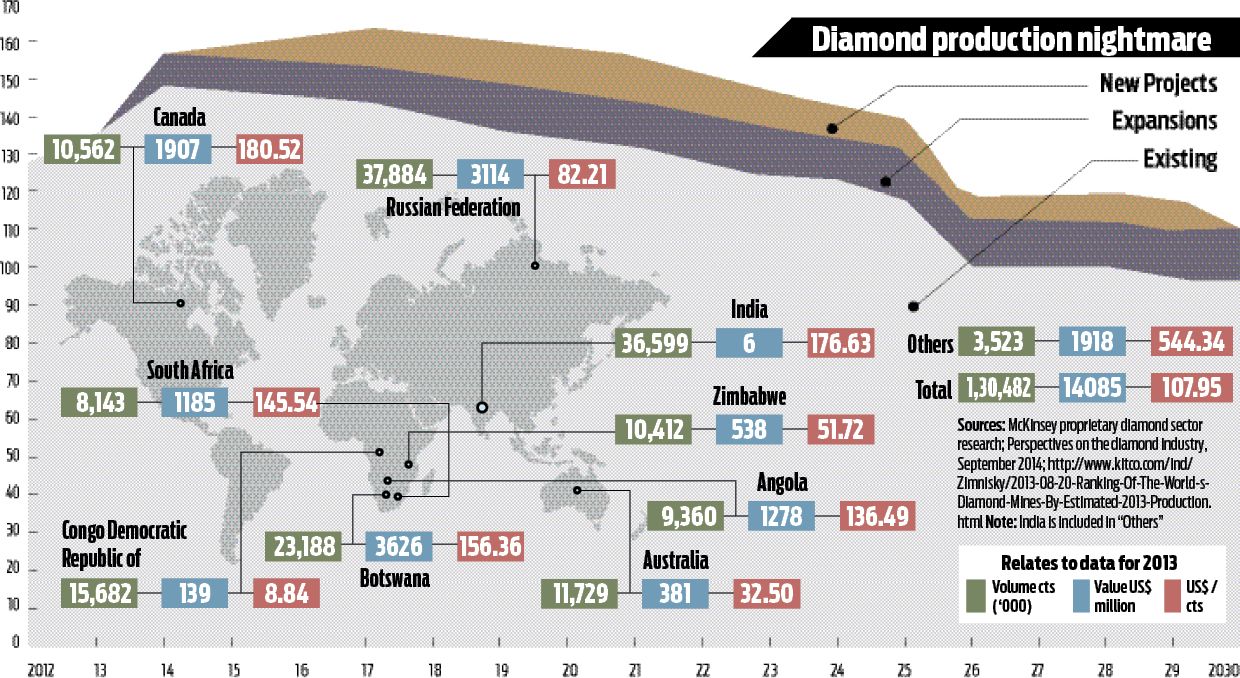

Consider the chart alongside:

Global production of rough diamonds is slated to decline. Some of the biggest mines are due for closure. Both Argyle in Australia and Ekati in Canada have a limited life of 7 years left. Rio Tinto’s Argyle has discovered a new mine, but that too may last just around 5-10 years. At such a time, India should be discouraging re-export of roughs. It should instead encourage import of diamonds from all possible sources to protect its 8 lakh strong CP workforce.

Evidently, the Gems & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC) does not think so. It has constantly persuaded India’s policymakers to invent new rules to block many import sources of rough diamonds. During the 1980s and the 1990s it actually persuaded the government to allow favourable import only for diamonds that were channelled through De Beers. Other sources of import, even from Russia, were sought to be slapped with additional import duty, if not banned.

During the past decade, India’s policymakers have confiscated roughs that were imported from places like Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. The reason: the GJEPC claimed that they had not adopted the Kimberly process. Sadly, no policymaker cared to notice that the countries singled out for violating the Kimberly process were the very ones that had chosen not to sell their diamonds through De Beers’ marketing channels. The coincidence is disturbing.

GJEPC is currently lobbying with India’s policymakers to slap additional import duties on lab-grown diamonds. And India’s policymakers still blithely believe that the supply of diamonds remains unaffected.

Take yet another factor that policymakers need to take cognisance of: In the diamond trade, the biggest profits go only to the miners and the retailers. In-betweens (especially India’s CP players) get squeezed. As pointed out by The Mining Journal, a rough diamond worth $100 assumes a value of $115 when sorted, $127 when cut and polished, $133 when traded through the dealing rooms, $166 when it goes into jewellery manufacturing and $320 at the retail level.

Unfortunately, the India diamond trade which can account for a value added (not profit margins) of $33 (even $37), is squeezed by miners on the one end, and by the retail trade at the other end. Lately, De Beers has been supplying more diamonds to global retail chains than to the Indian CP industry as it did before.

That is why it makes sense for India’s trade to opt for lab-grown diamonds that are around 25-30% cheaper than those sold by the miner cartels. First, it gives the Indian CP industry one more source of roughs in a world that is witnessing a shortage. Second, it lowers their inventory cost and allows them that much more of elbow room in a sector that is constant squeezed at both ends. Go back to the chart alongside. Watch how India’s mine production of diamonds has remained pathetically low, in spite of India-mined roughs commanding a higher value per carat ($176.63) than the world average ($107.95).

The only countries that have a better value per carat than that of Indian roughs are Canada ($180.52), Namibia ($802.24), Sierra Leone ($302.95), Lesotho ($584.88), Tanzania ($256.15), Guyana ($203.86), Liberia ($366.50) and Cameroon ($230.61) — see for more. Is it mere coincidence that most of these mining countries — especially in non-Caucasian Africa — have had trouble with the De Beers conglomerate at some point of time or the other?

India could have increased its own diamond mine production. But De Beers was given the rights to prospect in Madhya Pradesh. After two decades it backed out. Edward Jay Epstein, author of The Rise and Fall of Diamonds had predicted such tactics in his book — that De Beers does everything it can to grab a prospecting license, then sits on it, and eventually even thwarts the project, just to ensure that it can retain control of the global supply of diamonds.

This may or may not be true of India, but India’s policymakers have let it happen again. It gave the prospecting and mining license to Argyle (recently taken over by Rio Tinto) to exploit the Bunder diamond mine (with proven reserves). However, just last month, Rio Tinto decided to shelve the project indefinitely. Thus India’s 30-year engagement with De Beers/Argyle/Rio Tinto has ended up badly for the country, making it lose both time and opportunity.

Take one more instance. When a business transfers assets from India, and sends them to an affiliate in another country, it invites the provisions of ‘transfer pricing’; because it is a diversion of potential earnings away from India. Therefore, when an Indian diamantaire re-exports roughs, and is known to have another CP centre overseas, shouldn’t transfer pricing rules be made applicable here too?

Obviously, if “Make in India” has to be implemented effectively, India’s policies will need some drastic reviewing.

The author is a consulting editor with dna