“Suit the action to the word, the word to the action…” Hamlet.

Mimesis is a key element in classical Greek theory. However, in the colonial context, the introduction of Shakespeare lends mimesis another dimension, that which has been variously studied and investigated under the appellation “mimicry” by Homi Bhabha. Whilst the former is at the very heart of theatrical endeavour, mimicry, on the other hand, signifies an attempt to ‘mimic’ the white master, which despite its brilliance, will inevitably be fractured, and fall short. Between these two ends, are situated multifarious attempts to adapt and perform Shakespeare in the colonies. The genre of theatre encloses a multitude of voices and being a performative art, lends an eclecticism that can move it from mimicry to more authentic depictions. The ubiquitous appeal of Shakespeare as a poet who has an uncanny insight into the affairs of man is also another strain. It should also be said that an equally significant part of Shakespeare Studies has been about adaptation and it is extremely interesting to see adaptations of Shakespeare, many of which could qualify to be subversive in the colonial milieu where there were pressing parameters of race dictating these performances.

Punjab was the last province to fall into the kitty of the British Empire. In his book, A History of the Sikhs, Khushwant Singh explains Maharaja Ranjit Singh had a premonition about the same long before his death when, upon being shown a map of India with most parts in red (marking the extent of British territory), had stoically declared “Ek roz sab lal ho jayega” (It’ll all be red one day). His death in 1839 had spurred an ugly play of power games amongst his unwieldy line of successors and in the presence of the British who had a penchant to play power brokers. The inevitable happened and Punjab eventually fell into British hands. The education policy was subsequently formulated. The British influence on the system of education in Punjab thus began in right earnest. So Shakespeare entered through the classroom of English literature and the portals of Parsi theatre. These circumstances spurred the joining of Philips E Richards as a professor of English literature at the Dyal Singh College in Lahore in 1911. He was accompanied by Norah Richards, his wife who was an actress with the National Theatre in Dublin and soon developed a deep interest in the goings on at Lahore stage. It is, however, to be iterated that the Richards were Irish, and that more than anything else had a bearing on their attitude towards theatre in Lahore.

Punjab had a long unbroken tradition of folk forms like Bhands, Naqqals and Mirasis and they were integrated into the structure of a Punjab village in inextricable ways. Their performances were mandatory at weddings and childbirth. They were not, however, accorded respectability and were considered a shade lower in zaat (caste). Practitioners of theatre like Bawa Budhh Singh, Kirpa Sagar, B L Shastri etc were mostly writing plays drawn from existing folk, puranic and mythological stories. Bhai Vir Singh’s ‘Raja Lakhdata Singh’ (1910) was more of a closet drama that dramatised Sikh precepts but not so much with a view to be dramatised.

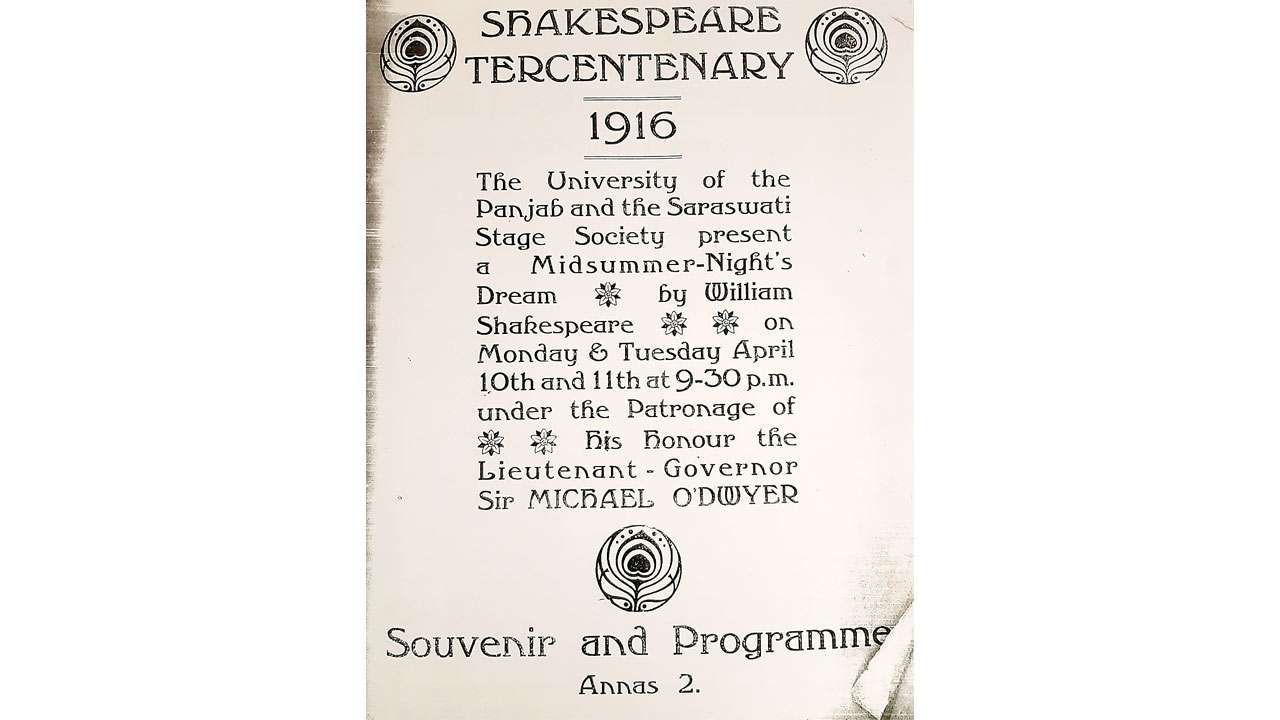

It is in this space that Norah Richards introduced Shakespeare in the classrooms and from there on University stage in Punjab. In 1916, on the tercentenary of Shakespeare, she directed a student production of “Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Subsequently under the rubric of Saraswati Society (A literary dramatics society founded by Richards), “The Merchant of Venice”, “As You Like It”, “Coriolanus” and “Twelfth Night” were performed. Her student IC Nanda, who went on to pioneer modern playwriting in Punjabi, had adapted “Merchant of Venice” into Punjabi as “Shamu Shah” in 1928. The connection was probably owing to the centrality of moneylender class in Punjab.

Shakespeare introduced in Punjab at this stage became a catalyst in inspiring new modes.

Apart from Shakespeare emanating from the English classroom of the likes of Norah Richards and other anglicised colleges, Parsi theatre was another font of Shakespeare productions in Lahore.

The Parsi theatre style employed proscenium stage, elaborate pageantry, spectacle and developed scripts from both Indian and Western texts. Its specialised “Shakespeare Natak Mandali” emerged as one of the leading troupes.

They undertook extensive translations of Shakespeare in Urdu and performed some shows in Lahore. Some important productions were: “Khun-e-nahaq”: 1898 (Hamlet), “Shahid-e-Wafa”: 1898 (Othello), “Dilfarosh”: 1900 (Merchant of Venice), “Safed Khun”: 1906 (King Lear) and “Gorakhdhanda”: 1909 (Comedy of Errors). In these circumstances, Shakespeare looks important to the extent that it became the third space, eventually giving way to the original one-act dramas in Punjabi. A spate of realistic dramas emerged that was to define the course of Punjabi theatre in times to come.

The author teaches English Literature and Cultural Studies and is currently on a Fellowship at IIAS, Shimla