Last week witnessed a resurgence of techno-nationalism in Asia. First, Chinese scientist Dr He Jiankui announced to the world his ability to use CRISPR-CAS9 technology on human embryos to create designer babies.

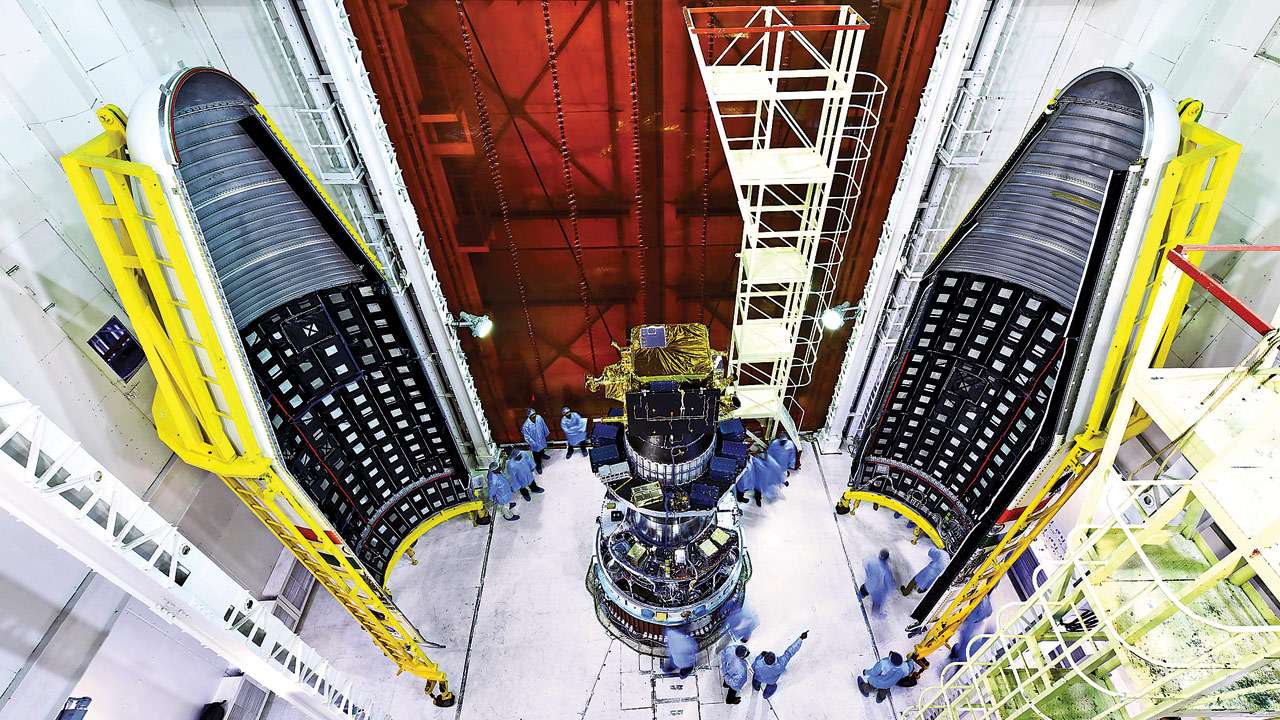

Next, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) successfully launched its latest earth observation satellite HysIS along with 30 other co-passenger satellites using its workhorse rocket PSLV-C43.

Xu Nanping, a Vice-Minister for Science and Technology in China, condemned the work of Jiankui according to BBC citing transgression of medical ethics and authorities clamped down on work by Jiankui as more on this still emerges.

Meanwhile, the Minister for Railways and Coal in India, Piyush Goyal, congratulated ISRO scientists and expressed the hope for using satellite imagery to better agriculture, forestry and geology.

Clearly, as national leaders converged in Argentina for G-20, policymakers from India and China were revelling in the race, albeit with mixed reactions. The Chinese wore cautious condemnation (though the Chinese Communist Party has earlier been reported to be keen about designer babies while supporting the Beijing Genomics Institute in Shenzhen), while Indians exhibited euphoric celebration. But this is not new.

Technology and science as a source of nationalistic pride was suggested by Christopher Freeman in his 1980s seminal work on national systems of innovation.

Several generations of scholars who study science and innovation policy too have found that in its conception, it could be a double-edged sword, with short and long-run positive and negative welfare implications, apart from several contradictions.

The first point of contradiction comes from whether the unit of analysis in this context should be nations. In 1947, Argentina first flew the Pulqui, a jet fighter made under the nationalist-populist Perón regime, a product created under the stewardship of France’s great aeronautical engineer, Emile Dewoitine, who was on the run from France (where he was wanted for collaboration with the Nazis).

He had arrived in Argentina in 1946 via Spain. Dewoitine stayed in Argentina till the 1960s and was subsequently replaced by an even more famous designer, Kurt Tank, the key designer at Focke-Wulf, who had Soviet Union connections, and who furthered Argentina’s unsuccessful Pulqui II programme.

Interestingly, Tank later moved to India where with his team he helped design the supersonic Hindustan Marut fighter, some 140 of which were built and were in service from the 1960s to the 1980s in India.

Clearly, even then for jet fighters, Franco-German expertise mattered and it travelled through tacit knowledge of individuals across nations and flowered under protectionist public sector technology and science programmes.

Here, national policy in terms of incentives to protect technology, scientist salaries and perks and the ability to forge co-invention teams with domestic scientists played an enabling role, but so did support from domestic philanthropists like JRD Tata’s work for aviation science in India showed in early 1900s.

Indeed, as research by Ina Ganguli shows, it is not just the scientists and inventors who matter but also the individuals who support science and technology.

The George Soros-funded special grants programme to over 28,000 Soviet scientists shortly after the end of the USSR, aided scientists to remain in science and more than doubled publications on the margin, as Ganguli has demonstrated in her paper.

But individuals are not the only source of techno-nationalism. There may be an important role of firms that may exhibit nation agnosticism. He Jiankui himself is a scientist-entrepreneur founder of a few firms in gene-sequencing, including Direct Genomics that have American scientists as advisors.

Here one is also reminded of Isaac Schoenberg of EMI and Vladimir Zworykin of RCA, both Russians, who developed their skills in television science with Boris Rosing before transferring them to US. RCA technology was actually first used to broadcast television in Russia before it went West.

A final word of caution on techno nationalism is merited also on its relationship with economic growth. While former Indian President Pranab Mukherjee has recently expressed disappointment that the Indian economy is not a $5 trillion+ economy yet, and has exhorted in other lectures the way forward with science, innovation and technology, the linkage here is not always clear.

For this, we can turn to the example of Italy and the United Kingdom who were very different in 1900, but not so in 2000. In the 1980s, Italy overtook the UK in output per head, a phenomena Italians termed as il sorpasso; Italy had become richer than Great Britain spending much less on R&D than Britain did.

But this was not a one-off event. Spain was one of the most successful European economies in terms of rates of growth in the 1980s and 1990s, and during this period spent less than 1 percent of GDP on R&D.

The understanding of this contradiction comes from an appreciation that while spending on R&D is important, the national innovation production function and the policy environment accompanying science and innovation ecosystem also matters.

Be that as it may, last week’s Asian triumphalism with Chinese designer babies and Indian space science prowess cannot be ignored. It may be reminiscent of Japan’s techno-superiority in East Asia a few decades earlier, but we may be entering an age where designer babies will be created by one country in Asia, while another will safely transport them into space.

Author is with IIM, Ahmedabad