The changes in the fiscal architecture of the country that the 14th Finance Commission (FC) imposed, coupled with the abolition of the Planning Commission, have had far-reaching consequences for public spending, especially for the social sectors. Four major shifts have occurred. First, from the national divisible pool of revenues the share of states was increased by 10 percentage points, that is from 32 per cent to 42 per cent, which is, on an average, about 30 per cent more untied resources for the states. Second, with the Centre’s share reduced, there has been a decline in allocations to several central or centrally sponsored schemes or worse still, closure of many schemes. Third, the 14th FC refrained from making any allocations for social sector programmes and the onus for funding many social sector programmes has shifted to the states. And, fourth, the 14th FC has made direct provisions for PRIs and urban local bodies as untied grants. In addition, the switch to GST, which the Centre controls, takes away state taxes like VAT and sales tax, entertainment tax, octroi and other local taxes and this reduces the state’s autonomy to raise its own revenues. Various states have responded differently to this but the general trajectory is that, on an average, the states are using the larger untied pool to increase their spending on infrastructure projects while neglecting the social sectors, especially health, education, ICDS, food security and other welfare and social security schemes.

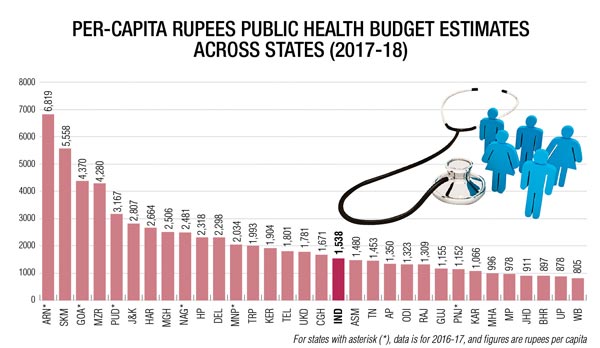

Public health budgets, which in most states were grossly inadequate, continue to remain low. Budget estimates for 2017-18 show that the Centre and state governments together have allocated about Rs 2,00,000 crore or Rs 1,538 per capita, which is a mere 1.18 per cent of the GDP and which is less than half of the promise of 2.5 per cent of the GDP made in the new health policy. The shortfall is Rs 1,37,000 crore. The graph shows the pattern of public health spending across states. There are 14 states which are spending below the national average, but they account for 84 per cent of the population and include the big states like Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, MP, Rajasthan and West Bengal, among others. There are 17 states which spend more than the national average but amongst them only seven spend more than Rs 2,592 per capita, which is equivalent to 2.5 per cent of the GDP. These top spenders are Arunachal, Sikkim, Goa, Mizoram, Puducherry, Jammu and Kashmir, and Haryana. Most of these states have robust health indicators and have strong primary health-care services being delivered through the public health system. What is also worth noting for these states is that except for Haryana, the other states do not have any significant private health sector and hence the public health system is forced to invest substantially in healthcare. In contrast, almost all the 14 states which spend less than the national average have a well-developed private health sector and the latter is perhaps the biggest reason for under-spending by these states. Other states which spend less than Rs 2,500 per capita but more than the national average are Kerala, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh and Meghalaya and they also do reasonably well in terms of health outcome indicators.

Further, in states which have a strong private health sector, especially amongst the 14 states spending below national average, there is an increasing reliance on health insurance schemes for secondary and tertiary care through state-sponsored schemes like RSBY, Arogyashri, Jeevandayi, Yashaswani, etc. In 2015-16 the government health insurance schemes almost doubled the coverage to 27 crore persons from 14 crore in 2012-13. This has resulted in Rs 2,500 crore from the public exchequer each year going mainly to subsidise the private sector. And what is interesting is that NSSO data reveals that these very states, which have resorted to the insurance model, are also the states where out-of-pocket expenditures have increased. So the insurance route is clearly undesirable because not only does it divert resources to the private health sector and deprives public health services adequate budgets, but it also fuels the private markets in health and increases out-of-pocket burdens on households.

So, the differential patterns of health spending we see across states conveys a very honest message that to provide for a reasonably robust health-care service, states need to invest at least Rs 2,500 per capita which will assure that the required infrastructure is in place and well maintained, will assure that all needed human resources are in place and all other inputs like medicines, diagnostics and equipment are adequately provided for.

Further, the unregulated growth of the private health sector and the increased reliance on health insurance to finance hospitalisations become a barrier to effective functioning of the public health sector. And we have good models of robust public health systems in states like Mizoram, Sikkim, Puducherry and Goa and there are no reasons why other states should not learn from them and emulate them.

The author is Country Coordinator, International Budget Partnership