They won’t be satisfied till they’ve had more,

The children of the dream

Who know what real dreaming is for.

Their hunger won’t be denied.

For they are draped in all the colours of the sun;

And they sing and grow from

Pain’s conviction.

Ben Okri, The Golden House of Sand

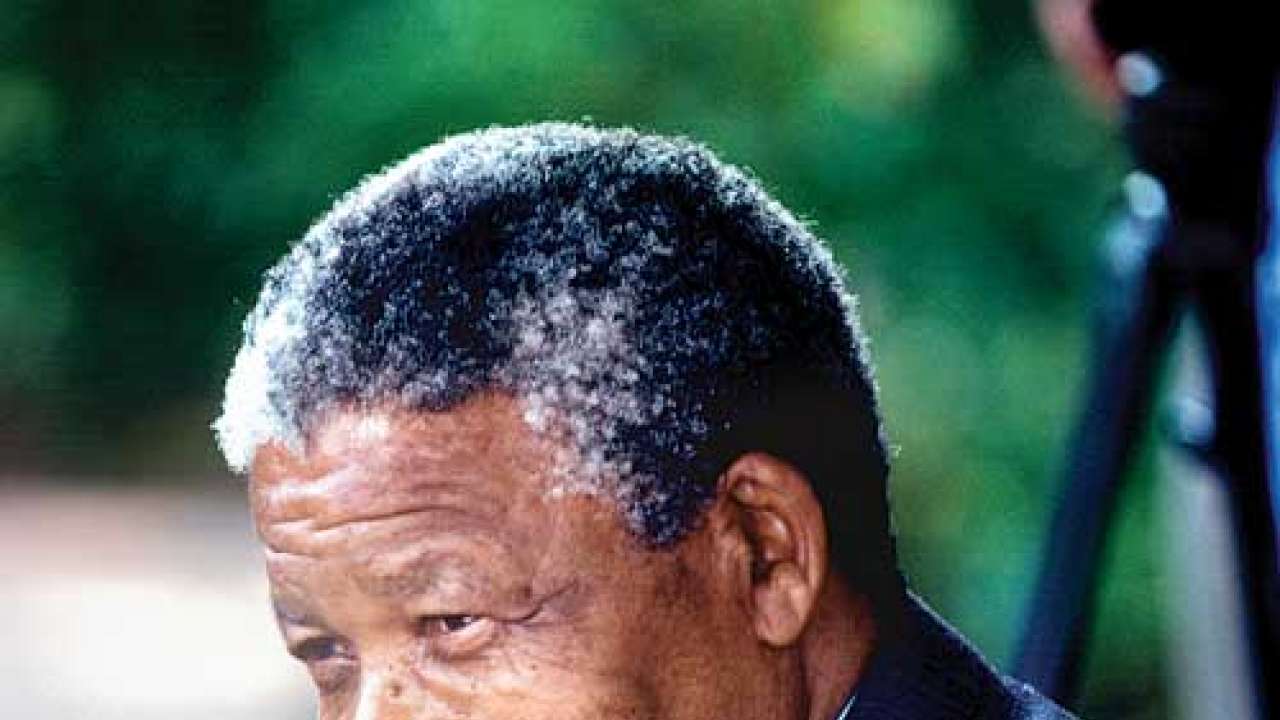

Were we ever truly prepared for this day? The protracted nature of his illness — hospitalisation following hospitalisation, the last one being the most relentless — along with the inescapable reality of his age meant that we’d convinced ourselves we were. We told ourselves we’d released him from our collective neediness for him. Yet the fateful moment revealed our hopeful delusions for what they were.

Our mourning exists on so many levels. We mourn as all children should, at the moment of their father’s passing. We mourn as all citizens should, when a man of great honour departs. But we also mourn because, as South Africans, we realise that the catcher of our collective dreams is no more. For so long we’d been content to be, in Ben Okri’s words, the children of his dream; shaped by the conviction of the pain he had endured and later draped as we were — his rainbow nation — “in all the colours of the sun”. We’d remember a time, when time was new, when he took his first steps as a free man again. We’d remember a time, when time was young, when he first spoke of his dream of reconciliation. And we’d remember a time, when time stood still, when he dared to dream again, of “the sun never setting on so glorious a human achievement.” Now, with his death comes the realisation that we can no longer be mere passive children of his vision. Now begins the long walk alone, where to honour his memory we need to be the builders upon the foundations of what he dreamt.

Nelson Mandela was born amidst the rolling hills of Mvezo, a rural village set amongst the savannah lands of the Eastern Cape. It is a haunting part of South Africa in which the sparseness of the undulating hills is set against the vastness of the African sky. As a youth herding his family’s flock of Nguni cattle in nearby Qunu, he would later recall staring out at the vast beyond of those hills, wondering what promise the rest of the world held for him. Filled with the tales of his royal ancestors — celebrated for their fight in defence of their land — he longed to add his own name to those of Dingane and Bambata, Hintsa and indomitable Moshoeshoe.

As a South African of Indian descent, reading his lyrical passages about Qunu (“the happiest days of my life”) calls to mind Jawaharlal Nehru’s similarly evocative descriptions of his ancestral seat in Kashmir. Yet while the Kashmir of Nehru’s youth was an idyll, the Eastern Cape of Mandela’s day was already bathed in horror and in bloodshed. For it was here, on the banks of the Great Fish River, that the original Frontier Wars had been fought between Boer and his Xhosa clansmen; a war of attrition waged for over a century and which, by Mandela’s day, had culminated in the great Land Act of 1913 which obliterated the tribal system and effectively robbed Africans of almost all their ancestral land, concentrating it in the hands of White power.

The young Mandela’s tribe had thus little land, and precious little power. As an urban immigrant in the 1940s, fleeing the imposed poverty of the hinterland to the industrial powerhouse of the Transvaal, he witnessed how countless of his people were reduced to a life slightly better than industrial serfdom. And as an African attorney in the 1950s (one of a handful in the country at the time) he saw what little power they did have, being systematically pushed back even further by a promulgation of laws meant to exclude people of colour from all aspects of South African society bar that of labour. His law practise became a home for opposing cases of police brutality.

By then he had already immersed himself at the confluence of law and politics. Joining and rising quickly through the ANC, he found its adherence to what he termed a “constitutional struggle”— trying to settle African grievances through peaceful discussion and contrite petitioning — too moderate. Instead, adopting the role of young agitator, he helped launch first the ANC Youth League as a vehicle to mobilise mass resistance, and then the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto We Sizwe, to meet government violence head-on. With this trajectory, it’s not surprising to guess where it would lead — particularly at the hands of a regime looking not just to suppress, but permanently remove all forms of dissent. Bannings, treason trials, and eventual life imprisonment.

From this, it is almost unimaginable how someone could emerge from a cell, 27 years later, championing peace and reconciliation. He had lost his youth and the human joys of family life for all those years, but the bitterness was not evident. Shunning retribution, he instead openly embraced his former enemy — be it his former prison guard, the prosecutor who had argued passionately for the death penalty, the widow of a chief architect of apartheid or even a former apartheid President, whom he made his Deputy in his first democratic Cabinet. With such acts, he taught us how to act with honour. And he taught us how to dream too, giving us the assurance, through his calm stewardship, that as father of our nation he would catch our dreams and make them a reality. And so we dared to dream; firstly that true forgiveness lies within all of us; and then that we could be a nation again — a nation at peace with each other and with ourselves. In each of these things, he lived up to his word and never disappointed us. Now it’s our turn not to disappoint him.

The author is a columnist for South Africa’s Daily Maverick, an online newspaper forum.