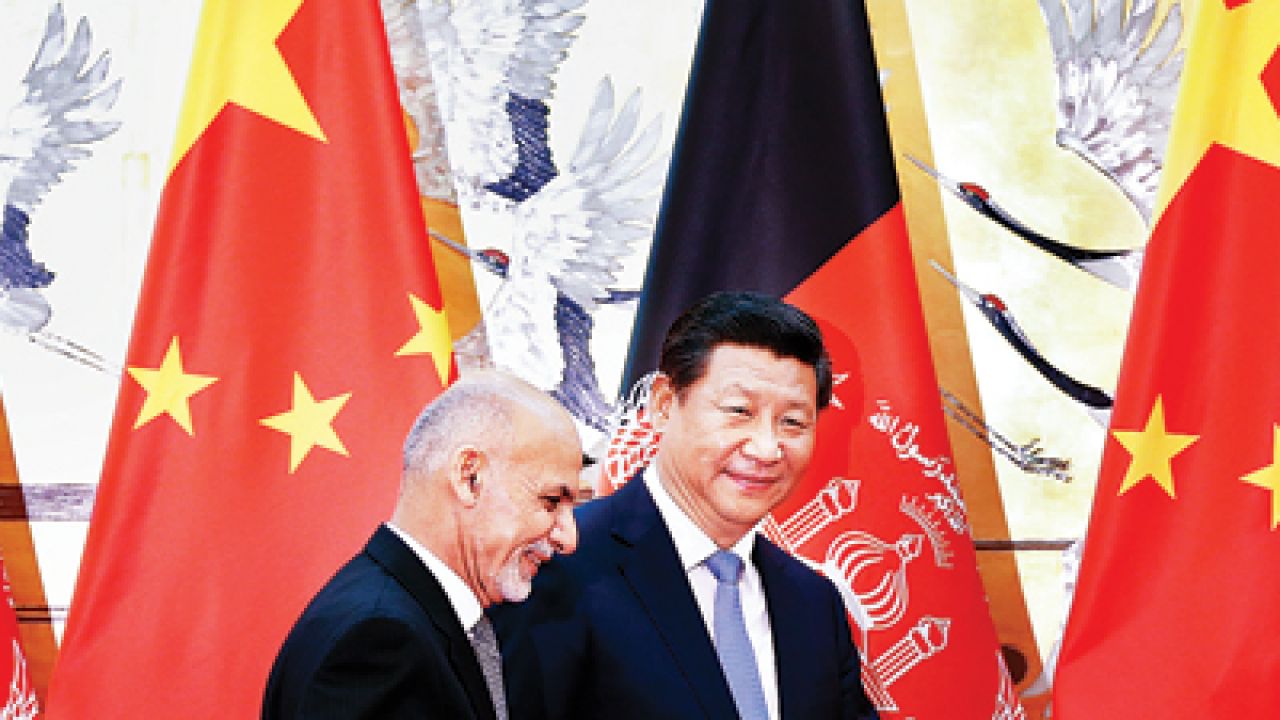

Little notice has been taken in India of the newly elected Afghan President Ashraf Ghani choosing Beijing as his first port of call after assuming office. In Beijing, the Afghan president also participated in a meeting of the foreign ministers of Russia and the Central Asian Republics hosted by China on October 31 — the fourth gathering of the “Istanbul Process” aimed at boosting development and security in Afghanistan. In rare praise for Beijing, the US State Department lauded its commitment to the region as the western troops begin pulling out.

Up to now, Beijing did not have to address the issue of internal stability of Afghanistan as the heavy lifting on that count was done by others. After the 2014 pullout, it cannot be business as usual for China in Afghanistan. The twin interests of China in Afghanistan are — protecting and expanding its commercial interests and preventing the Taliban from sheltering Uighur Islamic extremists from China’s restive Western province of Xinjiang. Neither objective can be achieved if Afghanistan takes a turn for the worse.

So far China’s aid to Afghanistan has been incommensurate with its size. Between 2002 and 2013, it amounted to US $252 million — less than that of Spain and Italy. The aid package of $327 million by 2017 promised by China during Ghani’s recent visit was not much bigger. Nevertheless, in describing China as a “reliable strategic partner” it is clear that Ghani would like China to get into a closer security embrace with Afghanistan. The Afghan President was clearly pressing the right buttons in promising security for Chinese investment in Afghanistan and support for the Chinese campaign against terrorism.

Afghanistan is rich in mineral resources. Estimated to be worth nearly one trillion dollars, they comprise copper, iron, gold, silver, chromite and lithium. Afghanistan also possesses an estimated 1.6 billion barrels of crude oil, 16 trillion feet of natural gas and 500 million barrels of natural gas liquids.

China’s hunger for minerals has already led it to Africa. Its insatiable need for energy has also made it the world’s largest importer of petroleum. There is every reason, therefore, to believe that the mineral, oil and gas resources in neighbouring Afghanistan are seen by Beijing as an attractive investment opportunity. China has already managed to acquire two concessions in Afghanistan — the Aynak copper mine in Logar province and the exploration of three oil blocks in the Amu Darya (Oxus River) basin.

However, security of investment and freedom of operations are major concerns for Chinese investment even as Ghani hopes that Beijing will make mining and the oil industry a major pillar of Afghan economy.

The state-owned Metallurgical Corporation of China and the Jiangxi Copper Corporation bid over $3 billion for the Aynak concession on a 30-year lease, yet it has been plagued with troubles. The project met with resistance after exploratory mining operations unearthed Buddhist stupas and artefacts. There are also security concerns as the Taliban pounded the Aynak site with rockets, forcing a pull out Chinese workers and officials from the site last year.

The oil and gas concessions seem much more promising as they are located in a relatively stable region extending along the Amu Darya from Afghanistan’s border with southern part of Tajikistan to southeastern Turkmenistan. China could link oil and gas from its three concessions in the Amu Darya basin to its pipeline network in Central Asia. The China National Petroleum Corporation plans an investment of $700 million in these oil blocks. Here too, however, the Chinese had to strike a deal with General Abdul Rasheed Dostum, whose local militia disrupted prospecting activities.

China’s internal security issues with Islamic Uighur separatists in Xinjiang also have an important Afghan dimension. Taliban have been sheltering and training the militants of the Eastern Turkmenistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) of the Uighurs in Afghanistan and in the tribal areas of Pakistan.

China, which is not opposed to the Taliban as such, has in the past tried to open a dialogue with them on the question of sheltering Uighur separatists. If there is a re-emergence and consolidation of the Taliban in Afghanistan after 2014, then Eastern Afghanistan could provide a staging post for the Uighurs for terrorist attacks on China. China has faced terrorist attacks from Uighur separatist not only in Xinjiang, but also in its capital Beijing and as far away in the east as Kunming, the capital of Yunan province. Despite its all-weather friendship with Pakistan, China has not been able to persuade Pakistan to act against the Uighurs and the ETIM extremists sheltering in its territory.

While China does not believe in interfering in the sovereign affairs of other countries directly, Beijing is involving Afghanistan on several fronts to address its concerns. During the Istanbul Process meeting, Beijing offered to facilitate along with Pakistan, a peace and reconciliation process between the Afghan government and the Taliban. This sends out a message that unlike the US and India, China is not opposed to the Taliban entering the government in Kabul provided they do not threaten Beijing’s commercial investments and are sensitive to its security interests vis-à-vis the Uighur extremists.

Almost in parallel, last month, China also proposed the setting up of a trilateral consultative mechanism between Afghanistan, China and Pakistan at the level of Vice Foreign Ministers to target the Uighur separatists of the ETIM. It also implies intelligence sharing, policy coordination and even organising joint operations against the ETIM. The objective seems to be to encourage both the Afghan and the Pakistan governments to specifically target the Uighurs sheltering in their respective territories. Such limited targeting of only China-specific terrorism would in principle allow Pakistan to deploy its Taliban proxy in strategic maneuvers in Afghanistan and India.

Should these two strategies meet with limited success, China is also joining or initiating attempts to put in place a multilateral framework involving Russia and the Central Asian countries to stabilise and secure Afghanistan — eg through the Istanbul Process and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. China’s commercial and political concerns about Uighur separatists may thus result in greater involvement with regional players in countering terrorism, including Uighur separatists.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist