The directive from the department of personnel and training (DoPT) is clear. Beginning July 15, each department of the central government will furnish a report by the 15th of every month about officers who could be considered for compulsory retirement.

The directive for implementing the provisions of Fundamental Rule 56 (j) and Rule 48 of CCS (Pension) Rules, 1972, is not new, but perhaps for the first time, the government means business in this context.

Such directives have been issued in the past as well, but this government has already demonstrated action on the ground by showing a number of officers the proverbial “door”.

The government, in its reply to the Lok Sabha, mentioned that between July 2014 and May 2019, about 312 officers of Group A and Group B Services have been recommended for compulsory retirement after reviewing performance of 36,756 officers of Group A and 82,654 officers of Group B.

On June 11, 2019, 12 senior officials of the income tax department, including those at the levels of commissioner, joint commissioner, additional commissioner and assistant commissioner, were retired compulsorily on charges of corruption.

The officers who approached the high courts for relief were not entertained. As a percentage of overall cadre strength, this is a small number, but it has indeed set the cat among the pigeons.

The message is loud and clear. This is an outcome of the instructions that each department should set up a two-member review committee, which will screen officers and employees based on internal feedback and yearly appraisal report.

The issue is being debated among civil servants and the public at large. There are a variety of questions being raised. There are also apprehensions that these provisions could be misused to push the officers to toe the line. Let us attempt to examine some of the issues.

First, is the government legally authorised to retire officers compulsorily? Second, it is desirable to do so? Third, is it a move to hound non-pliable officers and will it impact the morale of the civil service?

As mentioned in the opening paragraph, the government is well within its rights to compulsorily retire such officers on the grounds of corruption, misuse of public office, fraud and moral turpitude, among other charges.

However, only those officers can be considered for premature retirement who have completed 30 years of service or have crossed 50 years of age, whichever is earlier. There are clear-cut guidelines prescribed for retiring officers compulsorily. The instructions issued by the DoPT also quote from the judgments of the Supreme Court wherein it is clearly outlined that “the officer would live by reputation built around him. In appropriate case, there may not be sufficient evidence to take punitive disciplinary action of removal from the service, but his conduct and reputation is such that his continuance would be a menace to public service and injurious to public interest.”

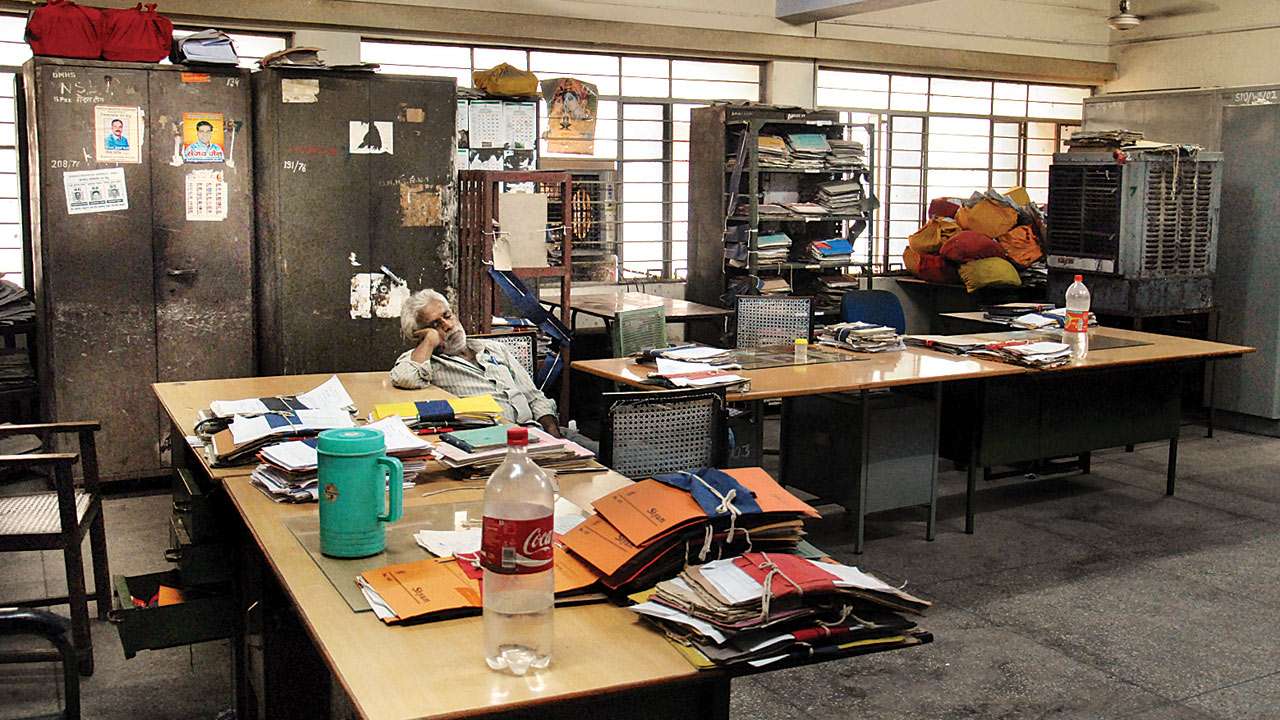

Given the fact that there is indeed some deadwood in the civil service, this appears to be a welcome move. Such officers need to be weeded out as their presence vitiates the service delivery environment.

The government and the civil service itself get a bad name on account of such officers, as even the media tends to highlight (rightly so) the misdeeds and misdemeanours of such officers. There are indeed a large number of committed officers in the civil service, but the presence of officers with dubious credentials creates an impression that these few corrupt represent the entire civil service! The objective of the exercise appears to be clear. Hence, to presume that it would be used to hound officers who don’t “comply”, is incorrect.

In any case, there has to be a clear cut case made out against the officers before any action can be taken. The instructions from the DoPT directs the “Ministries to ensure that the prescribed procedure, like forming an opinion to retire a government employee prematurely in public interest is strictly true, and that the decision is not an arbitrary one and is not based on collateral grounds”.

So there are sufficient safeguards embedded in the guidelines to ensure that the proposed action is not taken arbitrarily.

The honest and efficient officers should welcome this move. They not only have nothing to fear, but this step will prevent them from being clubbed with those that are corrupt and inefficient.

Indeed, the dishonest and inefficient are likely to suffer the most. These officers will, in all probability, be taken to task. The honest and inefficient will have to do some re-think. Their inefficiency is a drag on the system. They will have to soon realise that honesty alone is not enough. Honesty is necessary, but not a sufficient condition for a civil servant. They have to perform and make things happen on ground. The dishonest and efficient have survived in the system and, in some cases, have also thrived. This category of officers could also be on the run.

As in the case of many such instructions, it will all depend upon how such directives are actually implemented. Though there doesn’t appear to be an immediate apprehension, but these could well be used for settling scores and officers could be harassed.

However, as mentioned earlier, there are in-built mechanisms to prevent such a misuse. It is hoped that pro-active implementation of provisions that existed for decades, but not put to good use so far will improve administration and delivery of services.

Author is retired Union Secretary, Government of India