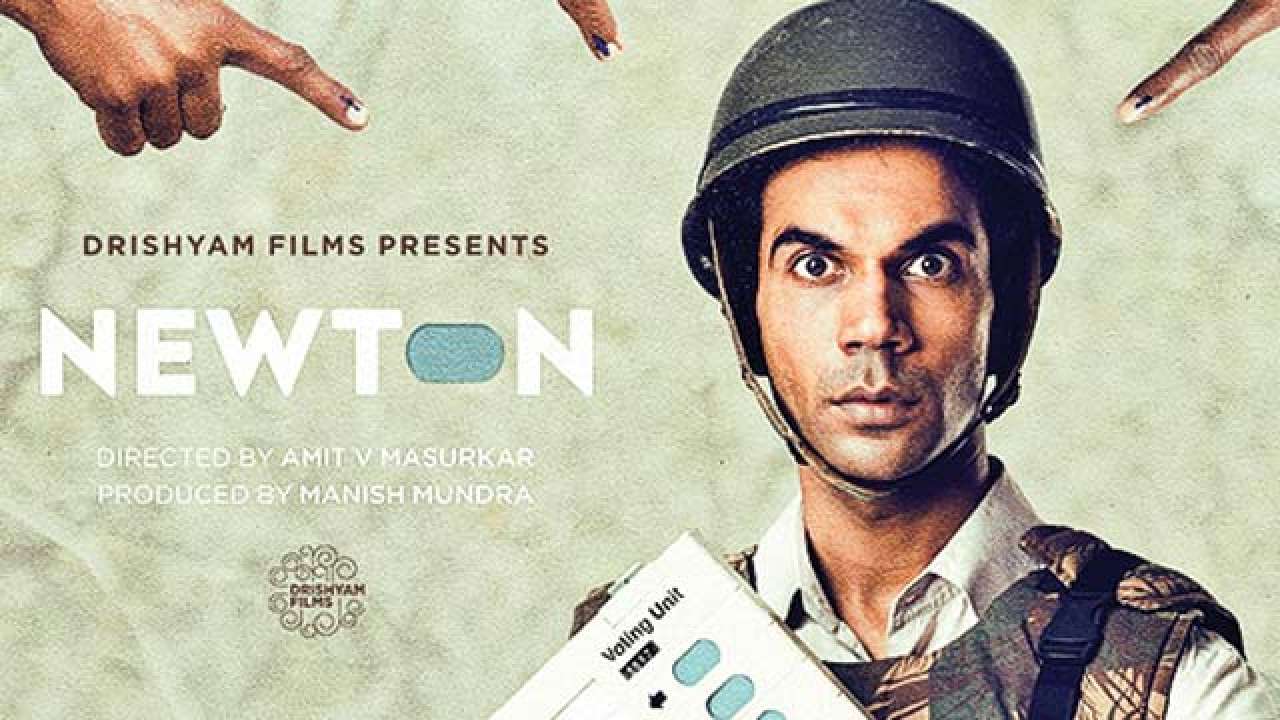

I finally got to see Newton when most people had stopped talking about it. The film had not only opened to good reviews, but its release on September 22, 2017, was greeted by its unanimous selection as India’s entry to the Oscars for 2018. A low-budget production made under Rs 10 crore, it also went on to earn over Rs 30 crore at the box office, with prospects of continued earnings in television and secondary broadcast rights.

Indeed, the film does not entirely disappoint. Both the theme and treatment hold the viewers’ interest, a steady stream of witty one-liners entertaining us when the plot flags. What really stands out, though, are the performances by Rajkummar Rao as the eponymous protagonist, Pankaj Tripathi as Aatma Singh, the leader of the paramilitary forces, and Newton’s antagonist, Anjali Patil as Malko, an Adivasi teacher, and Raghuveer Yadav as Loknath, Newton’s diabetic, cynical poll-booth co-officer.

So is Newton Oscar-worthy? Actually, the question is a non-starter if not a no-brainer. Since 1957, the year after the category of Best Foreign Language Film was created by the US Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Film Federation of India (FFI) has been sending entries on behalf of the Indian film fraternity. Except 2003, when no Indian film was found worthy, the FFI has sent its entry every single year. But no film nominated by it has ever won. In fact, the only Oscars Indians have won are in the individual category, Bhanu Athaiya’s 1983 award for the best costume design in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, followed by three awards for the Best Sound Recording (Resul Pookutty), Best Original Score (A R Rahman), and Best Original Song (A R Rahman and Gulzar), in Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire in 2009. Even Satyajit Ray, though nominated several times, never won. His 1992 award was honorary. Will Newton win? If FFI’s dismal record is anything to go by, the chances are slim.

The problem with single subject films like Newton is they rise or fall on how that one issue is worked out. Newton invited comparisons with the Iranian movie, Ballot Box (2001), accompanied by accusations of plagiarism. Both films show an incorruptible poll officer saving democracy by stubbornly following procedures. In Ballot Box, the officer is a burqa-clad female far-less naïve than Newton. A real crusader for democracy, she goes from door to door convincing reluctant voters on a remote island to vote. Amit Masurkar seems to have lifted this main idea but he has given it an Indian setting and twist. As Darab Farooqui, author of Dedh Ishqiya’s brilliant screenplay, puts it, Newton is “a completely new screenplay but its heart and soul are not original.”

Will this affect its chances at the Oscars? I’m not sure, but this lack of sincerity if not originality shows up its fault lines. Something about Newton simply does not ring true, starting with the very name of the protagonist. Like much of the social commentary in the film, it seems somewhat gimmicky. Consider the underage prospective bride whom Newton rejects. The situation looks contrived, an elite, urban projection, meant for the consumption of audiences in multiplexes. Similarly, when Newton asks Malko, “Kya aap nirashawadi hain?” She replies, “Nahi, main adivasi hoon.” One wonders who the joke is on — Malko, Newton, the other adivasis in the film, or on us?

Unlike Ballot Box, the danger to democracy in Newton is not from voter apathy, but from our own paramilitary forces, who stage an ambush to scuttle the voting before closing time. This makes little sense. Given that there are only 76 registered voters in that area, some of whom have already voted, why would the forces prevent the others from voting? What follows is even more bizarre: Newton seizes the assault rifle of the commander, forcing the election to continue at gunpoint. Not only are our troops malign, but they are utterly incompetent too? The Maoists shown killing a neta in the very first scene are exonerated. Instead, it is the Indian state that is shown to be blameworthy.

Newton’s caste is deliberately indeterminate, but he has been hailed as a Dalit champion, some even calling him, paradoxically, the modern Gandhi. The common clerk as a hero is a great idea, but there is nothing clerk-like nor common about Newton. He is the fantasy of politically correct scriptwriters inserted into a strange world where he sticks out like a sore thumb. The film reeks too much of the native informant pandering to Western left-liberals to make a really significant statement, whether poetic or political. It is thus another case of Indian modernity misunderstood and misrepresented. The film is not a black comedy, but shameless charade.

As a ‘patriotic’ Indian, I still wish it well at the Oscar sweepstakes.

The author is a poet and professor at JNU. Views expressed are personal.