Ghostwriting may be the oldest profession in the world, or at least one of the two oldest, which might explain the similarity of reactions they evoke. Jennie Erdal, who wrote Ghosting: A Double Life speaks of the time a professor from her university said she was “no better than a common whore”.

Erdal’s charming book — on ghosting for her employer, the flamboyant London publisher Naim Atallah (whom she calls ‘Tiger’) — caused a flutter when it appeared a decade ago. For ghostwriters, like spies, work in the shadows, and watch as other people take the credit for their work. Erdal’s was a warm portrait of Atallah, who however, broke off all relations once the book appeared.

"The plumage is a wonder to behold," Erdal wrote of Tiger's exuberant attire, "a large sapphire in the lapel of a bold striped suit, a vivid silk tie so bright that it dazzles, and when he flaps his wings the lining of his jacket glints and glistens like a prism."

The judgement of critics: this lady can write. Yet why was she satisfied with ghosting for her boss — writing everything from his letters, poems, love notes to his wife, novels — when it seemed like a wilful limiting of her potential? For two decades, Erdal hid her light under a bushel, content that Atallah claim all the glory. At the launch of one of “his” books, someone asked Erdal if she had read it. She varied her answer from “yes, it’s a classic”, to “no, but I hope to,” without ever sinking to “Read it? I wrote the bloody thing!”

“As a ghostwriter, you have to leave your ego at the door,” said the Sydney journalist Michael Robotham (who wrote the autobiography of Spice Girl Geri Halliwell) whose first novel became a best-seller in 26 countries. “Ghostwriters tend not to make the best novelists,” he said, “You are in a comfort zone as a ghostwriter. You earn very good money. And you don’t have your name on the book. So if it fails, you don’t fail publicly.”

Sports stars, movie actors, politicians, businessmen, all use ghosts to write their stuff. There is a certain logic to this. The great inside forward or the method actor need not simultaneously be the literary giant of his generation too. After all, a Hillary Clinton is not expected to fix her own car or build her own house, so why should she be expected to write her own book? Turn to the professional, therefore. And that’s what they do.

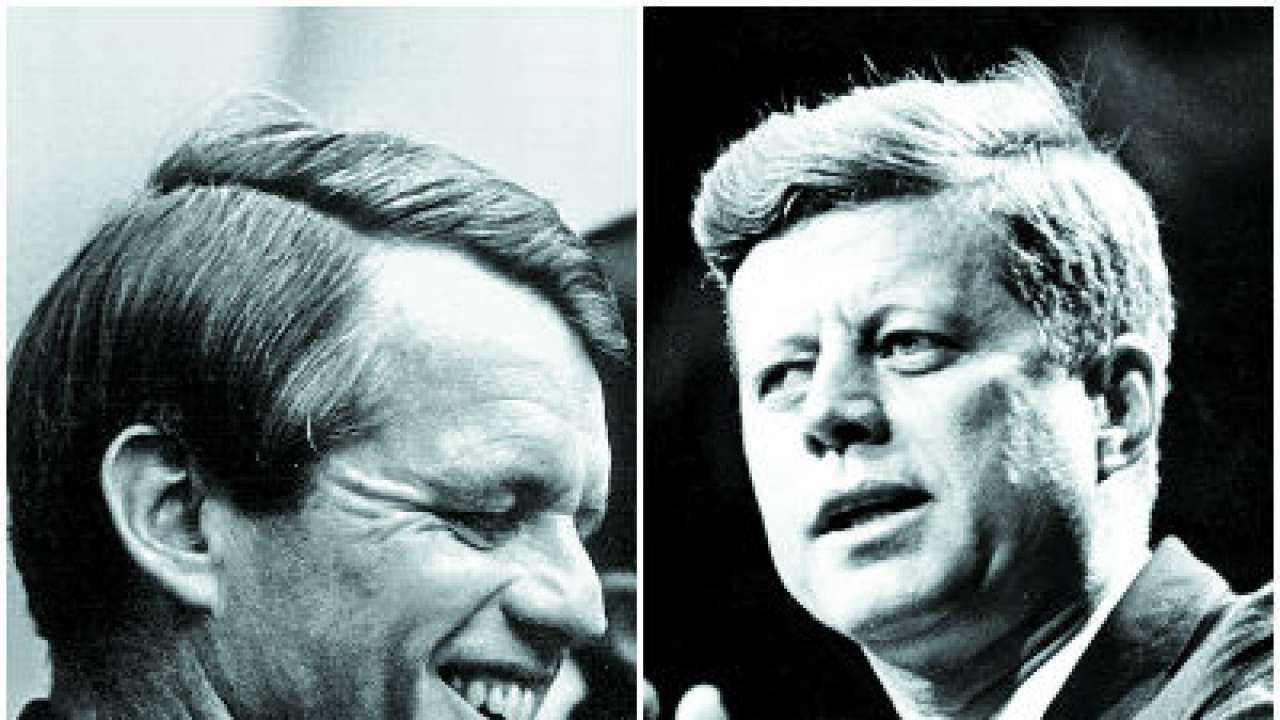

When President Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage won the Pulitzer Prize, there were at least two candidates who emerged as the likely ghostwriters. Arthur Schlesinger Jr and Ted Sorensen, both advisors to the President and speech writers. Years later, Sorensen wrote in his autobiography that he “did the first draft of most chapters and helped choose the words of many of its sentences.”

Many so-called prolific writers whose names appear in the record books for their phenomenal output used ghostwriters. Leslie Charteris was one. Many of the detective fiction writer Ellery Queen’s books were written by others. Before the franchise (James Bond, Bertie Wooster) took over, there was the book-churning industry. This was acknowledged by Mildred Wirt Benson, creator of the Nancy Drew series. Benson wrote for the Stratemeyer Syndicate in New York under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene.

Her identity was kept secret until it was revealed in a court case in the 1980s. The books were translated into 17 languages and sold more than 30 million copies. However, when she wrote under her own name, the books didn’t sell as well.

Next month, Andrew Crofts, one of the most successful writers of our generation, publishes his much-awaited Confessions of a Ghostwriter. A certain amount of de-masking is expected — “a bit of skirt-lifting, and more than a hint of saucy revelations,” as The Guardian put it — although that would be going against the ghost’s unwritten creed: Thou shalt not let down the ‘author’ whose name appears on the cover of the book. Crofts has written 80 books for various celebrities; these have sold over 10 million copies making him both rich and successful. His motto seems to be taken from something Harry S Truman said: “You can accomplish anything in life provided you don’t mind who gets the credit.”

Donald Bain, another veteran ghostwriter said he thought of writing as business, and had no ambition to be a Hemingway or a Grisham. Bain’s favourite quote is from Charles Dickens — another writer who thought of novels not as high art, but as avenues for money-making. “When you have quite done counting the sovereigns received for Pickwick, I should be much obliged to you to send me up a few,” Dickens wrote to a friend once. Bain has one way of getting his name into some of the books he writes — he dedicates them to himself.

One Nobel Prize winner ghosting for another might seem unreal, but when it is Gunter Grass (Literature, 1999) writing for Willy Brandt, the German Chancellor (Peace, 1971), then it becomes merely unusual. Grass’s romance with politics saw him write for the leader of the Social Democrats. The Citizen and His Voice was published in 1974.

Credit was very much the topic of the day when the footballer David Beckham won an award for his autobiography My Side. Did the award belong to him or to Tom Watt who actually wrote the book?

Ghostwriting is big business. The vanity of the celebrity is the fuel that keeps the wheels turning and the hack living a life that is the envy of those whose writings appear under their own names. There is too the Association of Ghostwriters, a professional network to “help writers connect with clients and refine their craft.”

Sportswriters are some of the finest ghostwriters in the world. A grunt by a sportsman to a banal question routinely appears in the media as a profundity from Socrates knocked into shape by Marquez. It is called “making the hero look (and sound) good.”

Christy Walsh, who set up a syndicate to exploit the literary output of America's sporting heroes had a rule: "Don't insult the intelligence of the public by claiming these men write their own stuff."

Or that they always speak intelligently even. The ghost is the sieve through which the banal is converted overnight into the brilliant for popular consumption. Ghostwriting, you might say, is a public service.

The author is Editor, Wisden India Almanack